Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

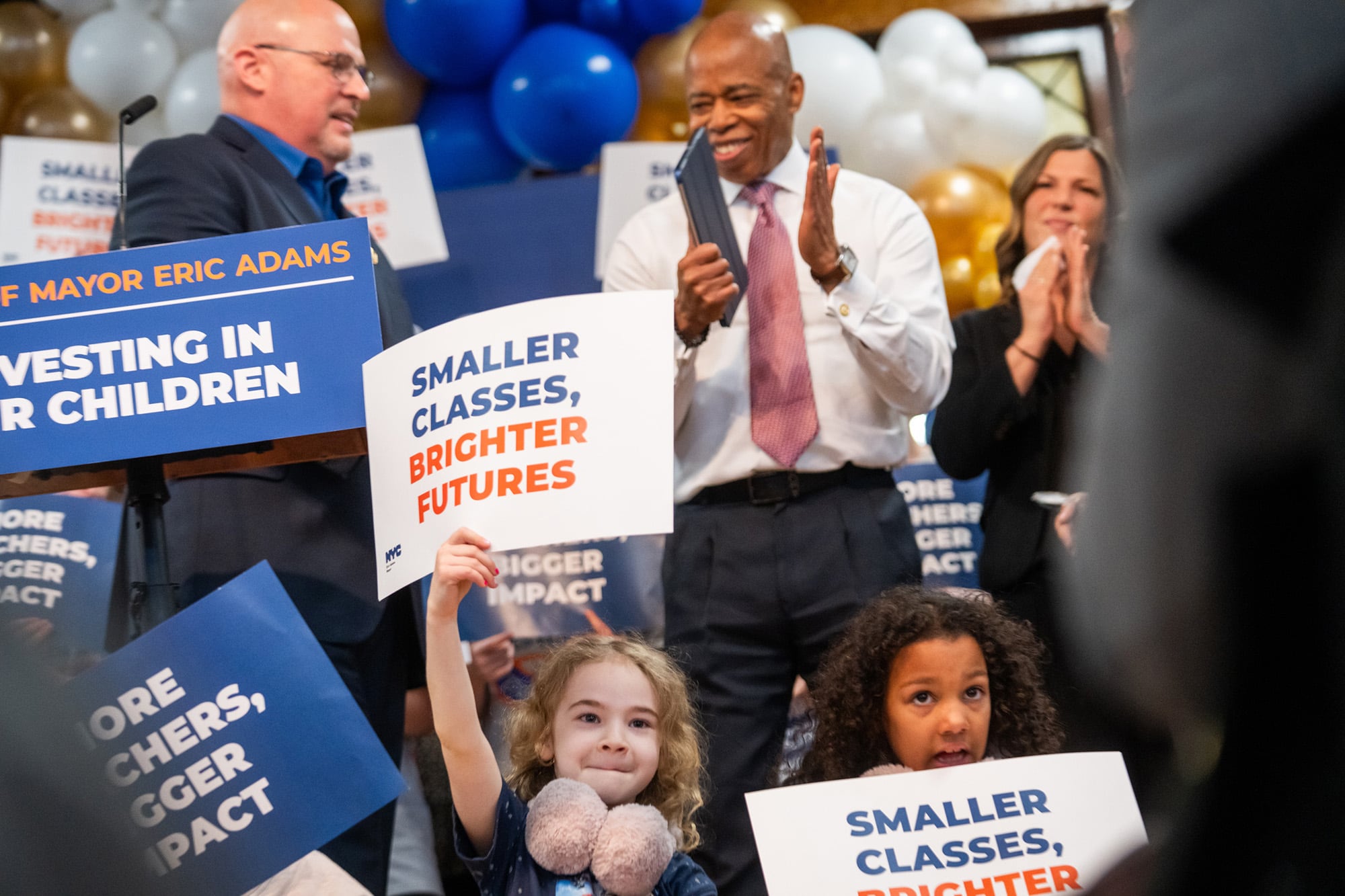

New York City Mayor Eric Adams announced Monday that the city met a high-stakes test under the state’s class size reduction law: ensuring 60% of this year’s classrooms fell under the new limits.

But he failed to mention that the city only cleared that hurdle by quietly declaring thousands of classrooms exempt from the requirements. A Chalkbeat analysis of data released Monday found that without the exemptions the city would have fallen just short of compliance, potentially putting it at risk of losing hundreds of millions of dollars in state aid.

Officials declared roughly 10,500 of the city’s more than 150,000 classes exempt. With those classrooms removed from the equation, 64% of classrooms citywide were in compliance — the rate city officials reported to the state. The city’s rate without the exemptions? 59.5%.

Several administrators and parents at schools with exempted classrooms said they were unaware they had won exemptions — and hadn’t requested them.

“I was a little surprised to see we were listed as exempt,” said one principal who didn’t ask for the exemptions and didn’t know they were coming.

“It’s ironic because they ask us to come up with a plan for our school … but then when they make larger decisions, they don’t ask us anything,” said the principal, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation.

The state’s sweeping class size law, which limits classes to between 20 and 25 students, took effect in 2022 and requires that an additional 20% of classrooms fall under the caps each year. This year’s 60% mandate was the first major test the city faced, since only 47% of classes were under the caps last November. (Classes that require larger groups like physical education are not subject to the caps.)

The challenge gets more daunting over the next year as the city races to get 80% of classes under the caps, soliciting another round of class size reduction plans from principals, who can request changes to their building configuration and money to hire additional teachers. City officials project the annual cost of hiring additional teachers could be as high as $1.7 billion when the caps are fully implemented, with up to $18 billion in school construction costs on top of that.

Some critics said the flood of exemptions this year heightens their concerns that the city will only lean more heavily on them in the years to come.

“It just underlines and emphasizes the fact that they don’t have a serious plan, and they never have,” said Leonie Haimson, the executive director of the advocacy group Class Size Matters and a key advocate for the state law.

To meet the state’s 60% threshold, the city spent roughly $450 million on a teacher hiring spree this fall — and took advantage for the first time of a clause in the law that allows some schools to ignore the requirements if they have limited space, are overenrolled, are in financial distress, or face a shortage of licensed teachers. The city exempted classes at more than 120 schools, Chalkbeat’s analysis found.

Teachers union officials confirmed Monday that principals were not directly involved in the exemption process. Under state law, the chancellor of the Education Department and the presidents of the unions for teachers and administrators can — and did — make the decisions.

“It’s not up to the school,” teachers union President Michael Mulgrew told Chalkbeat. “This is a law for the school system.”

An Education Department spokesperson said the exemptions must be renegotiated every year and schools that received exemptions this year should still aim for full class size compliance.

“Surpassing 60 percent of our class size reduction target for the 2025–2026 school year is a major step forward, and we’re not slowing down," Adams said in a statement.

Schools can get a pass for “overenrollment” or space limitations

A handful of the exemptions were already agreed to over the summer. In a class size plan released in July, city and union officials agreed to exempt the city’s eight specialized high schools, coveted programs like Stuyvesant and Brooklyn Tech that admit students based on a single test, on the grounds they are “overenrolled.”

Another set of schools could qualify for exemptions based on lack of space if a new annex or school building was in the works nearby, officials said in July. In the city’s two current capital plans, from 2020-24 and from 2025-29, a total of about 26,000 seats are supposed to be added in coming years through a combination of annexes and new buildings.

But people at several of the schools that received exemptions Monday said they were unaware of any annex or school construction plans nearby. At least three schools receiving class size exemptions had no new construction projects listed in their districts, according to the city’s data.

At P.S./I.S. 187 in Washington Heights, where 91 of 118 classes were issued exemptions, an annex project was recently added to the city’s capital plan to deliver 342 seats — but with no estimated completion date.

Olympia Kazi, a parent at the school who has been pushing for years for lower class sizes, said she was “saddened and dismayed” to learn about the exemptions.

“An annex may materialize at best in three to four years,” she said. “That means a generation of kids will still go through elementary school in overcrowded classes.”

Kazi noted that she suggested several other strategies for reducing class sizes while the school awaits additional space, including staggering start times for different groups of students and capping incoming kindergarten enrollment. Those ideas haven’t gone anywhere.

“I believe class size is a major issue for every school, and especially the overcrowded schools,” she said. “I wish there had been real community engagement before they decided any of this and an explanation of the reasoning behind this.”

Haimson believes granting the exemptions without including school communities in the process violates the spirit, if not the letter, of the law.

Having union officials help decide on exemptions at schools “where the principals don’t necessarily even want those exemptions, is bizarre,” she said.

Haimson added that new construction isn’t guaranteed to bring schools under the class size caps if the city doesn’t limit enrollment at overcrowded schools. Hundreds of schools don’t have the space to meet the class size caps, officials say, but the city has largely rejected requests to cap their enrollment.

Restricting enrollment is also a non-starter with the teachers union.

At the Boerum Hill School for International Studies, a 6-12 campus, more than half of the school’s 222 classes are exempt from the new class size caps. Antonia Ferraro Martinelli, the parent of a ninth grader at the school, said the campus is crunched for space in part because it houses four schools and there is little room to shrink classes.

News of the exemptions came as a surprise to parent leaders and the school administration, however, because they hadn’t requested them. The school’s principal is “putting her efforts toward being in compliance so this is coming out of left field,” said Ferraro Martinelli, who spoke with the principal on Monday. (The principal did not respond to a request for comment.)

Several educators and parents at schools that received exemptions said they plan to continue pushing to reduce class sizes.

In general, the city’s highest-need schools stand to benefit the least from the class size caps because they already tend to have smaller classes. A disproportionate share of spending to reduce class sizes is flowing to more affluent campuses, city data show. Because of that, some advocates with equity concerns called on city and state leaders last week to pause the class size caps entirely, a move permitted under the law.

Still, Education Department officials declined to request a pause, even as they previously raised similar equity concerns. Their reason: They’re making plenty of progress without it.

Correction: Nov. 20, 2025: A previous version of this story used the incorrect name for P.S./I.S. 187.

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.