Philadelphia’s high school admissions process has long been the subject of controversy because of the stark underrepresentation of Black and Latino students at the city’s top public schools. Past administrations have attempted to make changes, only to be stymied by backlash from mostly white families who say the magnet schools keep them in the city.

But with the country’s racial reckoning and a pandemic halting standardized tests, this could be an opportunity for a breakthrough.

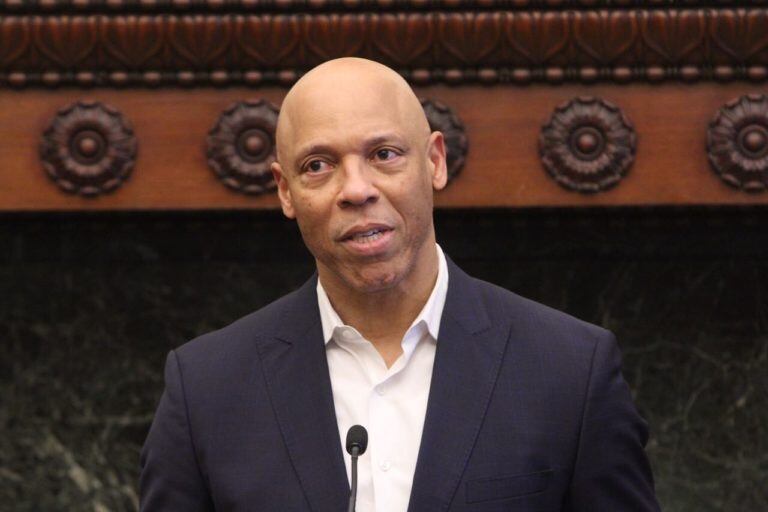

Superintendent William Hite told Chalkbeat he thinks Philadelphia might be more receptive to reimagining the admissions process following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the ensuing calls for racial justice. At the same time, the coronavirus pandemic and virtual schooling have upended the standard measures the district uses to determine student qualifications, not just state test scores but also attendance and grades.

“We’re using the pandemic to rethink everything. You don’t have the historical information that has always been used to make these decisions in the past,” Hite said in an interview.

Hite has launched a year-long district wide initiative, starting with a task force made up of staff but eventually meant to include parents and community members, to rethink policies and practices “through an equity lens.”

For instance, the percentages of Black and Latino students at the city’s premier magnets, Masterman and Central high schools, are way below their numbers in the district at large, and have been dropping. The frustration of Black alumni at these two schools broke open last month during the protests, compounded by the leak of racist and sexist private social media posts exchanged by some male students.

The equity coalition’s charge will include a look at the selective admissions policy, he said. For this year, the process will be some variation of the current system, with schools using sixth grade instead of seventh grade test scores.

For the long term, Hite said, “We have to think about a different approach we’re going to use, and we want to think critically about what are the opportunities within the new approach to provide more children with access...and what does that access look like,” he said.

Philadelphia is not the only district to deal with the racial imbalance in top-flight schools; it has also been a concern in New York City, where the sole criteria for eight schools is a single exam. But in contrast to New York, Philadelphia is a multi-tiered system that provides more opportunities for more students of all backgrounds but also has left neighborhood schools with bigger challenges.

What the data show

Philadelphia has a multi-tiered system of selective admission and citywide admission schools, as well as special programs within neighborhood schools. The options are impressive: schools that specialize in arts, engineering, science, agriculture, international affairs, history and government. There are former “vocational” schools that are now high-tech focused, as well as programs in neighborhood schools that offer training and certification in lucrative trades and technical specialties, from plumbing to web design.

The selective admissions schools have the most stringent requirements, starting with test scores in at least the 90th percentile for the most competitive and in the top 30% for others. The most selective are Central, one of the oldest high schools in the United States, and Masterman, which includes a middle school that starts in fifth and a smaller high school.

Other highly selective schools include Science Leadership Academy and the Academy at Palumbo, which were founded in the mid-2000s, and the Carver High School of Engineering and Science, Bodine High, and Creative and Performing Arts High, all established in the 1970s when the district was under pressure to desegregate.

Multiple studies have shown that Black and Latino students, who make up most of the district’s enrollment, are underrepresented at the most selective schools. In 2017, the Pew Charitable Trusts released a report showing that some ethnic groups, especially Latinos, were less likely to apply to top schools even if qualified, less likely to get in if they did apply, and less likely to go even if they were accepted.

In analyzing the admissions process, Hite and his team realized that each selective school had a different system for addressing waiting lists. Principals also have a lot of power in admissions decisions, with latitude to accept students who don’t meet qualifications if there’s room at the school. Some schools also hold auditions and require essays or interviews.

And then there’s what happens at Masterman — students must apply twice to the same school. They first apply in fifth grade and then — because the high school is smaller — they apply again for ninth grade. Any student who isn’t enrolled in Masterman’s middle school — for which third grade test scores were the most important admissions factor — has virtually no chance of getting into the high school.

In an effort to make the admissions process fairer at the top schools, Hite and his team made changes. In 2018, the district stopped giving principals information on race and gender. It also stopped giving them information on discipline records, including whether a student had been suspended. But even with those changes, the number of Black students continued declining, and some principals were concerned that they were not receiving vital information that could help them further diversify.

The district also embarked on some new initiatives. It notified every student who qualified for the top schools to apply, and some schools initiated outreach efforts. The High School of Engineering and Science, for instance, started a summer “bridge” program for students in nearby high-poverty schools to prepare students who might not otherwise qualify to tackle a rigorous curriculum. Carver’s population, unlike the other highly selective schools, is predominantly Black, but even it wasn’t reaching many students in the poorest neighborhoods.

“Every year we make improvements in the process,” said Karyn Lynch, the district’s chief of school support services whose office oversees school selection. “We’ve done outreach to eighth graders. We’ve reached out to seventh graders. We’ve met with K-8 and middle school leaders and met on numerous occasions with the principals who lead the special admission schools.”

The district’s Office of Evaluation, Research and Accountability also embarked on a three-part, comprehensive study of the application process for the four years between 2015-16 and 2018-19.

Students were divided into five groups based on the level of school for which they qualified for. The top two tiers were those who met “minimum” and “maximum” requirements for the city’s most sought-after schools, some like Central and Masterman which are more selective than others. The next tier was for those who met the qualifications for citywide schools, which includes most of the tech schools and most special programs within neighborhood high schools. The next group doesn’t meet the standard for citywide admission. The last group is comprised of those students with incomplete information.

Virtually all the students across all racial and ethnic groups who met the minimum qualifications — in the top two tiers — were accepted by the selective admissions schools. But there were vast differences in the percentage of students from each group who met the qualifications: just 9% of Black applicants and 11% of Latinos, compared to 49% of Asians and 31% of whites.

An even smaller percentage met the standards for those in the top tier, with test scores in the 90th percentile or above. According to the data, of those students who met that criteria, only 14% were Black students and 6.6% were Latino students, numbers that mirror the demographic breakdown in Central and Masterman today.

As a result, there are huge disparities in the percentages of students who get offers to attend the most selective schools based on race and ethnicity.

About 80% of Asian students were accepted, compared to around 65% of white students, and fewer than 40% of Black students and Latinos. The success rate for students who identified as multi-racial was about half. Overall, 42% of applicants to selective schools were accepted.

Racial distinctions were evident even among students who didn’t meet the admissions standards but were accepted because of space: higher percentages of white and Asian students were offered spots than Black students or Latinos.

“The main issue is not the acceptance rate,” said Tonya Wolford, the district’s chief of the research office. “The acceptance rate for qualified applicants is similar across student groups. You have to consider the entire pipeline, choices students and families make, the desirability of different programs for different students, and student qualifications for the different programs.”

Asian students, for instance, are more likely to “reach” for schools even if not technically qualified, much more so than Black students and Latinos. And when they do, they are more likely to be admitted, the report notes.

“Findings from these reports about under-qualified admissions has directly led to work, happening right now, about identifying under-qualified students that might successfully “reach” in this fashion - and making that segment of the process more equitable,” she said.

How this might happen, however, will be the charge of Hite’s new equity commission.

Hite said a new metric could, for instance, include a “point” system in which students receive points for diversity, based on the school they attend and their zip code.

“There are things we can think about now because we don’t have the necessary information [due to the pandemic] to use the systems already in place,” he said.

Efforts have failed in the past

Coming up with a new approach will not be easy. In 2010, Superintendent Arlene Ackerman — who had helped run other school districts — ordered subordinates to design a new application system after declaring that she had never seen such a tiered high school admissions process as in Philadelphia. The officials devised a 1,000-point system that included 200 points for “diversity.” After the new process was leaked and caused a furor, she quickly disavowed it.

More than a decade earlier, Superintendent David Hornbeck had also given it a try. He changed admissions criteria to some specialty schools and programs in the city to make them accessible by lottery and broaden the diversity of the students they admitted. Even though the changes did not touch the most selective schools like Central and Masterman, the move caused consternation.

The Board of Education finally had to come up with a compromise: students had to meet standards before they could enter the lottery. The issue had gained so much attention that Mayor Ed Rendell, generally a staunch Hornbeck supporter, had a press conference in City Hall to announce the new policy.

There are signs that today, people might be more receptive.

As part of the racial reckoning and citywide unrest that followed the death of George Floyd, alumni from Central and Masterman went public with bitter memories of their experiences at the city’s two most selective schools and reminders that the Black population at the schools has continued to decline. They issued statements demanding change — including a new look at the admissions process — which the schools’ principals agreed to carefully consider. The uprising at Central and Masterman partly inspired Hite’s equity initiative.

Masterman’s faculty, through its building committee, endorsed the calls for change, including what it termed a “reconstruction of admissions policies.” Some Central teachers have also issued a statement of support.

Hite thinks the atmosphere might be ripe now for a permanent shift.

“I do think the mood has changed,” he said. “More individuals are pointing to this as one of the systemic inequities we faced in Philadelphia for many years.”

Plus, he added, students are now speaking up about their own experiences and putting them in the context of systemic racism. “Young people, students are saying it now,” he noted.

‘It’s worth a try’

But more must happen besides tweaking the qualifications for these schools, said Kendra Brooks, who was elected last year to an at-large seat on City Council on the strength of her education activism.

Brooks recalls as a parent of four children in North Philadelphia trying to navigate the system’s complex special admissions maze. It wasn’t easy.

In addition to the difficulties negotiating a mostly online process, she points out that schools in her neighborhood didn’t have enough counselors, teachers didn’t have enough support in their classrooms, and behavioral health services were scarce. In her experience, she said, it wasn’t uncommon for teachers and counselors to subtly or overtly discourage students from neighborhoods in the poorest communities, like the one her children attended, from applying for the top schools.

“One of my daughters wasn’t the best academically, and when we started talking about the application process, we were told immediately that she shouldn’t apply to certain schools,” Brooks said.

She thinks that relying on test scores is problematic because it encourages teaching to the test, and the scores neither give a good sense of a student’s abilities nor encourage the best kind of teaching and learning. She said she “opted out” two of her children from taking the test, forcing the district to consider other factors in her children’s special admissions applications. Both of her children still in the system attend special admission schools, Science Leadership Academy and Hill-Freedman.

Stephanie King, a white parent of two who lives in Northern Liberties, has done extensive analyses of which students end up at the most selective schools. She concluded that nearly a quarter of Masterman’s students come from four elementary schools, all of which are whiter and wealthier than the norm: Penn-Alexander, Meredith, Greenfield, and McCall. She finds this appalling.

King sent her two children to her neighborhood school, Kearny Elementary, whose enrollment is almost entirely low-income and Black, even though the area has a growing contingent of young white families.

Her daughter will be entering Masterman this year, although she said they thought long and hard about staying at Kearny. Her son is in the first grade. King said her daughter chose Masterman because she could more easily join the Philadelphia Student Union and agitate for change. “And she liked the library.”

Plus, she added, she was surprised how proud the Kearny community was that one of their students got into Masterman, “even if it was the white kid.”

But King told her daughter she could always go back to Kearny.

“I’m sorry to be pessimistic, but what I have seen is that most white parents’ engagement with the idea of racial justice and equity is very shallow,” King said. “I’ve seen a ton of Black Lives Matter signs, but not a single white kindergartener registered in Kearny’s incoming class. I don’t believe that the current moment is going to lead to white people to give up any privilege to create a more equitable education system.”

Brooks wants to believe with Hite that this moment heralds a real reckoning. She said that she sees a new resolve on the part of some teachers, communities, and school leaders. “Nobody wants to be on the bad side of it,” she said. “I don’t know. It’s worth a try. I think the effort should be there.”

But fundamentally, she agrees with King.

“I think you’ll still get the same pushback as before,” she said. “The biases are still there, the assumptions that creating equity for low-income children is somehow taking away from more affluent families. That’s a belief I think that persists even in the middle of Black Lives Matter.”

Neena Hagen, an intern with the Philadelphia Public School Notebook, completed data analysis and contributed reporting.