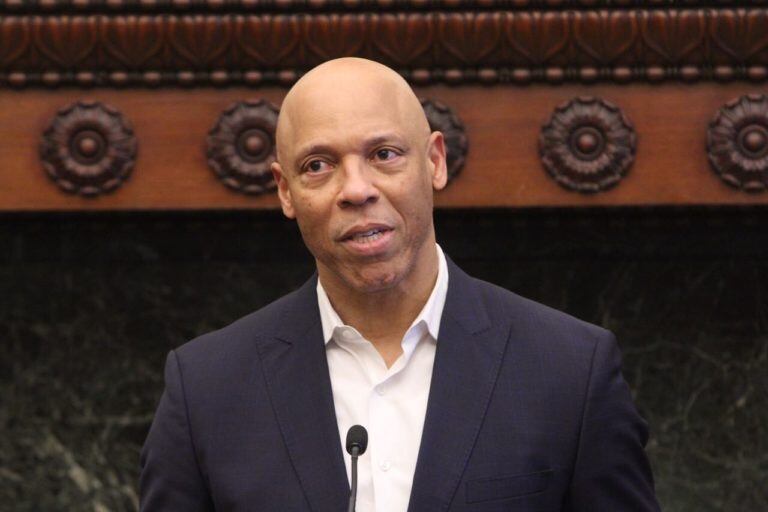

Philadelphia school superintendent William Hite spent Tuesday testifying at the school funding trial in Harrisburg, reiterating several times that he believes a lack of resources is the main reason that more Philadelphia students do not achieve academically at high levels.

Hite, who is leaving the state’s largest district in August after a decade as superintendent, said he agreed to testify in the trial “in order to make sure that in the future, whoever comes in after me … should not face the same types of circumstances I’ve had to face in trying to educate children without sufficient resources and support to do so.”

The trial, before Commonwealth Court Judge Renée Cohn Jubelirer, comes in a case that seeks to overhaul the state’s school funding system. Pennsylvania has some of the widest spending gaps in the nation between wealthy and low-income school districts, and ranks 45th in the nation in the percentage of education costs borne by the state as opposed to localities.

This case, originally filed in 2014, is the latest in several such cases in Pennsylvania, but it is the first that has made it to trial. Previous judges have ruled that the issue of school funding is a matter for the legislature, not judicial intervention.

Philadelphia, the state’s largest district by far, was under state control at the time the suit was filed and is not a plaintiff in the case, which was brought by six districts, three families — including one from the city — and two statewide advocacy groups. The Philadelphia Board of Education has passed a resolution endorsing the suit and expressing hope that it will result in more revenue being available to educate city students.

The plaintiffs sued the governor, legislature, and Pennsylvania Department of Education, but only the Republican legislative leadership is mounting a defense.

Under questioning from attorney Kristina Moon of the Education Law Center, which is helping represent the plaintiffs, Hite painted the picture of a district in the nation’s poorest big city with increasing needs and insufficient funding to meet them.

For instance, 12% of students in district schools are English language learners, with more than 100 languages spoken as first languages by its families, and 17% percent of students have disabilities. Both are higher than the state average. Additionally, thousands of students experience homelessness or are in the foster care system, Hite said.

“Are you sufficiently staffed to meet student needs?” Moon asked.

“We are not,” Hite answered.

Most of the district’s students are low-income, so many that the district simply provides free breakfast and lunch to all students because it is cheaper that way rather than doing the paperwork to determine who exactly is eligible. All but three of the district’s 216 schools have a student body poor enough for the whole school to qualify for federal Title I funds, which targets low-income students.

The English learner population grew from 8% to 12% in less than a decade. But due to budget constraints and other limitations, the district has been unable to hire enough teachers of English as a Second Language or Bilingual Counseling Assistants to work in schools, Hite said.

In other states where he has worked, including Georgia and Maryland, school funding made an effort to keep up with needs, he said. Districts there “all had budgetary challenges,” he said. But in those places policymakers saw to it that “funding caught up with expenditures moving forward,” especially after federal stimulus money from the 2008 recession ran out.

In Philadelphia, however, “the experience was very different.”

Hite became superintendent in 2012. With federal funds expiring, then-Governor Tom Corbett, a Republican, slashed state aid to schools, with Philadelphia losing a quarter of a billion dollars. Some of Hite’s first acts were to lay off nurses, counselors, and other school employees not strictly mandated by state law, and to cut extracurricular activities. Many schools opened with just teachers and a principal, and hardly any other staff. Within his first few years, he also closed 24 schools.

Gradually, the district regained its financial footing, but it came at great cost.

“It doesn’t instill a lot of trust in an educational entity when you talk about opening schools with just teachers and principals and without extracurricular activities and other things that for families and children would represent what schools are,” he said.

Moon led Hite through a comparison of Lower Merion and Overbrook high schools, which are barely three miles apart, but which have vastly different demographics and student outcomes.

Overbrook’s student body is almost entirely Black and low income, and its performance on the state Keystone exams is low, with just 6% of students scoring proficient or advanced. At Lower Merion, which is mostly white and affluent, 94.9% of students are at least proficient.

High percentages of the relatively low number of economically disadvantaged students at Lower Merion score proficient on the tests, 80.6% in English, 87.5% in algebra, and 72.2% in biology. That contrasts with figures in the low single digits for economically disadvantaged students at Overbrook. Not one low-income student scored proficient in the biology test at Overbrook, Hite said.

“Is there any reason Overbrook’s students or any Philadelphia students are not capable of reaching Lower Merion’s level of achievement?” Moon asked.

“Other than funding, no,” Hite said, “and making sure young people have access to the type of resources Lower Merion enjoys.” Lower Merion spends nearly $27,000 per student, among the highest of the state’s 500 districts, compared with less than $20,000 per student in Philadelphia.

Moon also led Hite through the story of how Mitchell Elementary School in West Philadelphia improved its test scores when it got additional resources as part of the district’s acceleration network, formerly called the turnaround network, that focused on improving schools with very low achievement.

From 2015 to 2019 Mitchell got extra staff positions, including reading and math coaches, a counselor, and an assistant principal. It showed big jumps in reading, math, and science scores from 2017-18 to 2019-20, although overall achievement levels still remained low. “The overall progress was trending in the right direction,” Hite said.

Mitchell improved enough that it exited the acceleration network, and lost its extra funding — other schools needed it more. “I am concerned about that, but it’s an unfortunate product of having to triage resources due to the availability of funds,” he said.

Overall, Hite said, “we are not graduating children who are college and career ready” based on the results on standardized tests and other measures. “Every day I walk into a school and see what’s there and what could be done [with sufficient funds] and it becomes discouraging, unfortunate, and sad for me personally.”

Attorney John Krill, representing Senate President Jake Corman, started his cross examination of Hite, pressing him to quantify how much more in personnel and resources it would take to bring all Mitchell students to 100% proficiency on math and reading.

Hite avoided giving a specific number. “When you have schools with low proficiency, two significant things should happen: sufficient resources to meet whatever needs of those children are, and those resources need to be sustainable, predictable and recurring,” he responded.

There will be no public court session Wednesday. Krill will resume cross examination of Hite Thursday. Attorney Patrick Northen, who is representing House Speaker Brian Cutler, will not participate in cross examination because his law firm, Dilworth Paxson LLP, does work for the Philadelphia district.

Other planned witnesses from Philadelphia include Chief Financial Officer Uri Monson and a school principal and counselor.