Sign up for Chalkbeat Philadelphia’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system.

Two months in, Philadelphia’s year-round school program is blossoming, officials say. But so far, the effort seems focused on giving more families access to programs that already existed, rather than revising the academic calendar.

Mayor Cherelle Parker continues to tout the program as a new vision for the city’s schools and the realization of her campaign promise. But she’s shifted her characterization of it from “year-round” school to “extended-day, extended-year” school. Across the 20 district schools and five charter schools piloting the free extended-day, extended-year program, the city and school district have doubled the number of after-school seats and created thousands of before-school seats at some schools for the first time.

Maritza Velez, a parent, grandparent, and foster caregiver of students at William Cramp Elementary School, said being part of the pilot program has allowed Cramp to open a before-care program for the first time this year.

“It’s great for parents that work,” Velez said.

But for most of the pilot schools, “year-round school” at this point mainly appears to be a new name for work that schools and nonprofit providers have been doing for years.

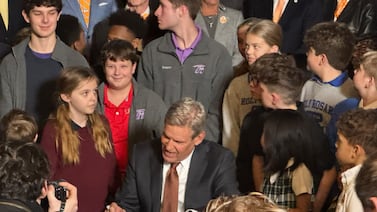

On Tuesday, Parker, Superintendent Tony Watlington, Chief Education Officer Debora Carrera, and other school officials toured Southwark Elementary School — one of the pilot schools. They answered kindergartners’ questions, watched fourth grade girls operate camera tripods, and chatted with other students flying drones and building with Legos.

But those programs are not new this year. They’re not even exclusive to the pilot program. The media lab is run by the public media organization WHYY, which has operated in several Philly schools for eight years. And the kindergarten class and robotics club are supported by Sunrise of Philadelphia, a nonprofit that’s been partnering with Southwark to deliver their after-school programming for more than 25 years.

Sunrise also provides free out-of-school programming to 13 other district schools — only one of which is in the pilot program.

That’s not to say educators don’t appreciate what’s going on this year. Southwark Principal Andrew Lukov said Tuesday that the pilot program has allowed the school to increase access to its after-school offerings to a larger number of families than before. Lukov called that a “big game changer.”

“Sometimes you have to tell families ‘no’ when we know that they really need these before-school services,” Lukov said. He emphasized that most of his students started their school journeys during the pandemic and are still adjusting to post-COVID education and socialization: “Our kids love being here.”

The year-round school pilot is funded by $24 million that comes from an increase in the school district’s share of property tax revenue.

Parents want clearer information about extended-day programs

So far, the main function of the pilot this year appears to be expanding access.

This year, Carrera said schools have been able to nearly double the after-school seats from 1,435 last year to 2,555 this year, and add 1,400 before-school seats in 14 of the district pilot schools — the remaining six schools already open early when other schools are offering before-care.

The number of after-school seats at the five pilot charter schools has more than doubled from 228 last year to 514 this year.

The pilot schools will also be open during winter and spring break in December, January, and April, and for six weeks in the summer, but regular academic classes won’t be in session. Some 2,000 students are expected to participate in the winter and spring programming, according to the mayor’s office.

Still, that means the extended-day pilot is only serving a small fraction of the roughly 176,900 students enrolled in Philly district and charter schools.

Parents at the pilot schools told Chalkbeat they’re mostly happy with the services, but wish there was clearer communication about what exactly “year-round” school is.

“I’ve heard a little bit about it but I do feel like the communication can be improved,” Shayonna Brazelton, a Cramp parent, said. “What are the requirements? Do you have to fill out an application to sign the kids up? Is it going to be in every school, or just select schools, and then [what is] the duration? I know they’re extending the day but how many hours is it?”

Davida Smith, another Cramp parent, said she thinks year-round school is a good idea in theory, especially for older kids. Smith was in the first graduating class at Grover Washington Middle School, which tried out its own year-round school model starting in 2000 that ended after four years.

“They should start it maybe with high school because the way things are going on in the city right now, keeping high school kids in school during the summer” is a good idea, Smith said. “But for the younger ones, they’re not so much there yet. Don’t put so much on these ones yet.”

Elias Corbin, the community schools coordinator at Cramp, said parent feedback about the school’s new before-school program has been overwhelmingly positive. Participating in the pilot has also allowed Cramp to lift the cap on their preexisting after-school program from 36 seats to 60 seats. According to district data, Cramp enrolls nearly 350 students.

Corbin said the school’s biggest challenge is finding qualified people to staff the program.

Indeed, staffing has been an ongoing question since the pilot started. Watlington and Parker have been clear that no educators will be required to work outside of their contracted hours and no collective bargaining agreements will be changed without negotiations with the two relevant employee unions, the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers and Commonwealth Association of School Administrators.

Watlington said he’s meeting regularly with union leadership. “We’re talking about what this might look like in the future as we expand.”

Arthur Steinberg, president of the PFT, said how people refer to the concept— year-round school, extended-day school, community school — “matters far less” than ensuring that the programs themselves improve student achievement.

“As we proceed with negotiations for a new labor contract, we at the PFT expect to be heard and respected with regard to our members’ roles and responsibilities in expanding community schooling,” Steinberg said in an email.

But regardless of the name and the specifics, Brazelton said she welcomes the program’s intention.

“We are losing our recreational programs and things like that, so there is not as much for the children to do when they’re not in school,” she said. “I feel like anything that we can do in the city to give the kids more options so they don’t have to turn to the streets, the violence, YouTube — to put them in social environments, to be around other kids their age, and to be learning and growing together, that’s always a good idea.”

Carly Sitrin is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Philadelphia. Contact Carly at csitrin@chalkbeat.org.