Sign up for Chalkbeat Philadelphia’s free newsletter to keep up with news on the city’s public school system.

Throughout the 2024-25 school year, Chalkbeat Philadelphia is following a new teacher, Kahn-Tineta Smith, as she adapts to the joys and challenges of working in the city school district. This is the third and final check-in we hope will shine a light on the state of the Philadelphia teaching workforce. Read the first entry here, and the second entry here.

The soft voice piped up from the edge of the gaggle of preschoolers on the rug.

“Green and white,” said Jazzlyn. A simple observation, but also a milestone.

The 4-year-old in Kahn-Tineta Smith’s Head Start classroom was nonverbal when school started in September. As the school year neared its end, Jazzlyn is saying words and she knows her colors, accurately describing a picture of several plants and herbs that Smith had projected onto the whiteboard.

“And she’s more social,” Smith said. “This helps her pick up more skills from her peers.”

Smith, 53, is wrapping up her first year as a Head Start teacher at Mary McLeod Bethune Elementary School in North Philadelphia. She reached that point after raising her three children and working for two decades as a classroom aide. She accomplished this through the Para Pathway program, a collaboration between the district and the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers that helps paraprofessionals become certified teachers by paying for associate and bachelor’s degrees.

Chalkbeat has been following Smith during her first year as a Philly teacher. It was a learning experience for her as well as for the children. Having Jazzlyn speak and participate in class has been among her proudest moments, but as with any new teacher, there have been difficult moments in her journey too. She has had to adjust to dealing with as many as 20 children at a time – all with their own needs, their own skills, their own styles of interacting with others.

But over the course of the year, she also “became more confident to trust my instincts.”

She remembers a day that she became frustrated when she was teaching the children their letters, and one of her students just wasn’t catching on. But then she realized that the child was struggling with literacy. She pulled her aside for individual reading sessions, talked to her parents, and started the process of evaluation for special education services and applying for a one-on-one aide.

“I learned to be calm, be more patient, be more understanding, and to implement my lesson so that children could understand me. I learned how to talk to them at their level,” she said.

Her biggest challenge, she said, was establishing a classroom routine and balancing the dictates of the curriculum with her own judgment on what would work best for the children, and what they needed at that moment.

Her experience as a mother helped. But parenting is different from being responsible for a room full of other people’s children and launching them on their journey to being students. And her training, including her six weeks as a student teacher in a second grade classroom, didn’t fully prepare her for her day-to-day responsibilities.

Luckily, she said, “organization is my best skill, and that’s what helped me through the year.”

And overall, she’s very pleased with how her inaugural year in the classroom turned out.

“I think I made a great decision,” she said. “I’m glad I went back to school and fulfilled my dream to become a teacher.

Paraprofessional program aims to help ease Philly teacher shortage

Since 2022, 118 paraprofessionals have completed Para Pathway, and 87 are currently teaching in city schools, according to the district. Another 64 people are enrolled.

To underwrite the cost, the district used $2.5 million in federal COVID aid supplemented by $1.7 million in other funds.

The program is meant to help address Philadelphia’s persistent teacher shortage – but that problem can’t be solved by Para Pathway alone. District schools started in September with more than 450 vacancies for teacher positions and have struggled all year to fill them. And while there are more than 2,500 paraprofessionals in the district, a relatively small subset are interested in or suited to becoming teachers.

PFT spokesperson Jane Roh said that the union considers Para Pathway to be part of “a long-term solution for growing the teacher pipeline.” She added that union leaders hope the program continues to get support regardless of what happens with federal funding.

Smith used the funding from Para Pathway to get her certification from Cheyney University. It changed her life. She is thrilled with what she’s accomplished with her first group of 18 students (down from 20 when the school year started) in her colorfully decorated basement classroom.

Among her students, she said, there were no serious behavior problems. Because her classroom has both 3- and 4-year-olds, six or seven of her younger students will be returning next year, and she is looking forward to observing their growth.

Her accomplishments during her first year aren’t limited to her basement space. Smith is proud of how she can help address student needs outside the classroom by recommending them and their families for special services.

“I can communicate with parents more, which I couldn’t do when I was a classroom assistant,” she said.

As happy as Smith is with what she has been able to accomplish, she’s also conscious of what’s going on in national politics, especially plans and actions from Congress and the Trump administration.

Smith is especially concerned about potential reductions to Medicaid and nutrition assistance to low-income families that could impact her children, many of whose families rely on those benefits. As part of the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Adrienne Chapman, a health educator from Jefferson Einstein Hospital, visited Smith’s classroom on a recent Monday to talk with her students about proper nutrition.

“We’re afraid people will lose access to healthy foods,” Chapman said.

Smith is also concerned that the federal government could slash aid for students with disabilities and for early childhood programs. Although President Donald Trump’s proposed budget would keep Head Start funding flat in the next fiscal year, the program has been affected by funding delays and the Trump administration’s attempts to cut costs across the federal government.

Another visitor to Smith’s class on that Monday was an occupational therapist from Elwyn Early Learning Services, who came to work with a student with special needs. The little girl doesn’t talk; during story time she goes off by herself instead of gathering on the rug with her classmates.

As the rest of the class participated in story time, the Elwyn therapist helped the girl with her favorite activity, organizing dolls and other manipulatives.

“It’s terrible,” Smith said of possible cuts that would affect her students. “I don’t know why they want to cut things that are important and needed by children and families. These things were in place when I was in high school, when my kids were in high school. Children need early education, and they need special services if they have some type of disability.”

‘My students are learning what I’m teaching’

Regardless, Smith sees to it that her classroom is both under control and full of activity.

She loves even the mundane and messy parts of the job, like her first task on most mornings: distributing the Cheerios and milk from the children’s federally subsidized breakfast and sweeping up the cereal bits that, inevitably, find their way to the floor.

“We don’t use our hands, we use our spoons,” she reminded the children as they eat.

When one child complains “I don’t have no milk,” both Smith and her experienced teacher’s assistant, Anita Parker, are quick to correct her. “I don’t have any milk,” they say.

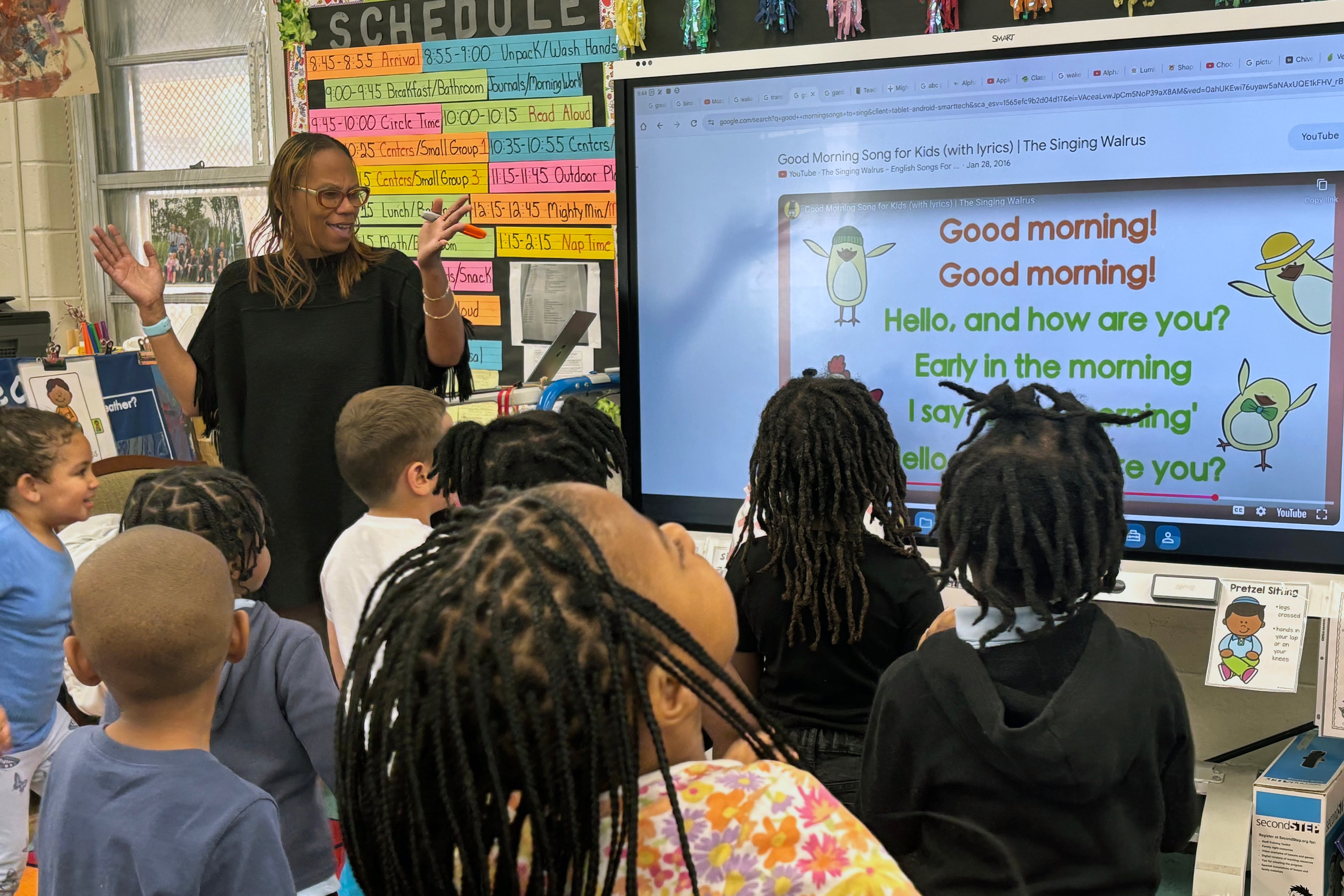

After the orderly bathroom breaks, Smith gets down to business – having the children sing each of their names, one at a time, to the tune of “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” The exercise helps students demonstrate “phonological awareness, phonics skills and word recognition,” according to the curriculum guidelines.

“‘Kerry, how many syllables in ‘Kerry?’” she asks after they sing and clap.

“Two,” they shout. Same with “Dessiah.” This time the answer is “three.” They clap once for each syllable.

When they have gone through all the names, which have the children swaying and bouncing in their circle on the rug, Smith asks students to describe what they see in the pictures of herbs and plants projected on the whiteboard. She writes down their answers: a tree, flowers, grass, vegetables.

And then came the answer from the usually quiet Jazzlyn: “green and white.”

Moments like these are validating. My greatest satisfaction is knowing that my students are learning what I’m teaching.” I can tell when they are grasping the information and retaining it.”

With her early childhood education degree Smith could teach up to grade 4, and her dream is one day to run a pre-K program or even a K-8 school of her own.

“I’m a natural,” she says with a smile, not bragging but stating the obvious. “I’m stern, and I love them. They see the love and feel the sternness. They know I am only here for them.”

Dale Mezzacappa is a former senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia and reported for The Philadelphia Inquirer, where she covered K-12 schools and early childhood education.