This story was reported by Denise Clay-Murray and published by MindSite News.

KIPP North Philadelphia Academy charter school has been operating since 2018 in the red brick school building on North 16th Street at Cumberland Street. Bright KIPP banners hang off the four-story building but you can still see the fading letters “M Hall Stanton” on the facade.

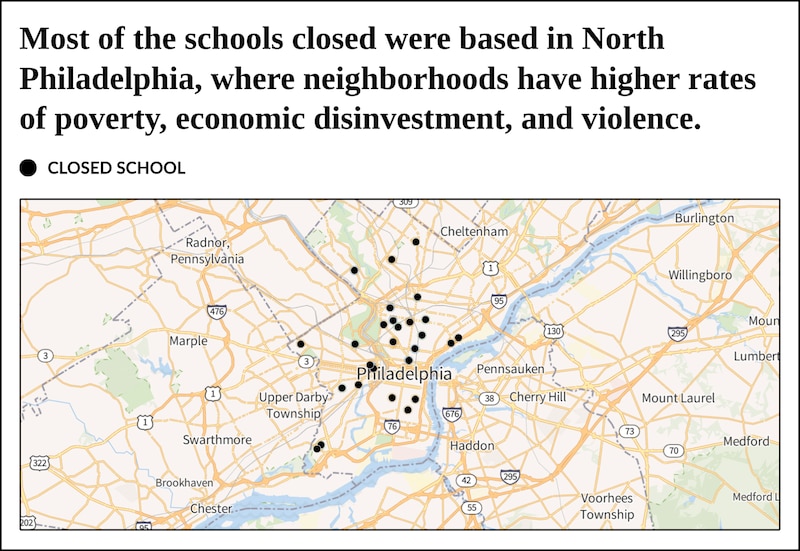

That’s because KIPP only moved in after the Philadelphia School District closed down M. Hall Stanton Elementary as part of a massive change that shuttered 30 schools over a two-year stretch from 2012 to 2014. The district was struggling to close a projected $1.35 billion deficit and said it needed to consolidate to put scarce dollars into the classroom.

When Stanton opened in 1960, Philadelphia’s overall population had peaked, and this part of North Philly was growing. It was built with enough classrooms for 1,300 students spread over four floors. A report from the National Register of Historic Places said its “modern design, the work of local firm Ehrlich and Levinson, was an important sign of investment in a struggling neighborhood” when it opened.

For decades, the school was anchored in the community. Its 450-seat auditorium hosted community meetings and for many years, its classrooms were used in the evenings for adult education. It may get emptied again since the Philadelphia Board of Education has begun the process of revoking its charter. The district is also poised to close a number of other Philadelphia public schools as it again grapples with declining enrollment, aging buildings in need of major repairs, and some schools with hundreds of empty seats.

When that happens, neighborhoods like this part of North Philadelphia may again be confronted with the loss of a vital institution.

As the city’s school board prepares to debate this new round of closures, a question raised by community advocates before and after the last round is likely to reemerge: Did shutting down 30 schools more than a decade ago exacerbate Philadelphia’s gun violence by destabilizing those neighborhoods and removing key social institutions?

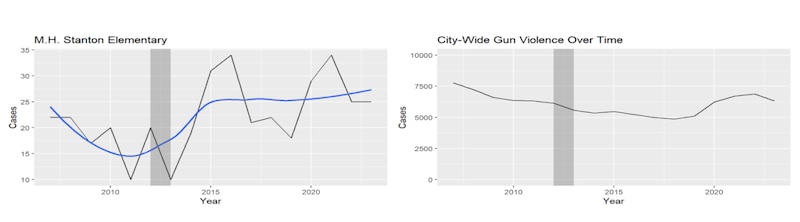

To try to answer that question, the Philadelphia Journalism Collaborative and MindSite News used public gun violence and crime data obtained from the Philadelphia Police Department to plot gun-related crimes that occurred within 500 yards of schools from 2006 to 2024. We wanted to know whether gun violence rose and fell at different rates around open and closed schools.

The data show that among the 30 shuttered schools, there were 12 where gun violence either stopped improving or worsened after the closure in ways that don’t follow the citywide trend. Another 13 schools that were shut down had inconclusive trends or ones that mainly paralleled the citywide numbers. Five others saw a decrease in nearby gun violence over that period.

For the Stanton site, gun violence near the school — which had declined in the years preceding its closing in 2013 — began rising after the school closed at a rate that outpaced the increases in violence that occurred across the city. From 2006 through 2024, 434 acts of gun violence occurred within 500 yards of the school, the data show. (Five hundred yards is equivalent to five football fields.)The data don’t prove school closings lead to higher gun violence, but they do show areas where it worsened after closure that can’t be explained by spikes in gun violence across the city.

Neighborhoods feel the impact

The fact that Stanton and some other closed schools saw gun violence worsen comes as no surprise to Chantay Love.

When a school is closed, it creates a sense of loss and changes the character of the neighborhood, said Love, executive director of the EMIR Healing Center in Philadelphia’s Germantown section. EMIR, an acronym for Every Murder Is Real, is named for Love’s brother who was lost to gun violence. It’s a nonprofit organization that provides support services for those who have been impacted by shootings.

“Just like we convene around different entities, communities convene around schools,” Love told MindSite News. “It’s because they’re a cheering space, not only for the neighborhood but also for the young people. It becomes their second home. It’s where they get to thrive and develop. And when it’s taken away from them, the nuance of the neighborhood is removed.”

While crime has always existed in low-income neighborhoods, “there were certain things you just didn’t do around a school,” Love said. “And no matter who was around, they protected all children. This was the sacred place. It was extended home. By closing schools, you leave a hole in the neighborhood.”

As early as 1993, Stanton Elementary was in the news because the urban school received so much less funding than its suburban neighbors — an inequity in school funding that has persisted into the present.

That year, HBO aired the documentary “I Am A Promise: The Children of Stanton Elementary School” as part of its “America Undercover” documentary series. The film, which went on to win both an Emmy and an Academy Award, followed former principal Deanna Burney as she attempted to help the students and teachers at Stanton navigate their academic work while simultaneously dealing with such outside forces as poverty, disinvestment, drug abuse, and violence.

Despite the best efforts of Burney and her staff, the documentary ended with her resignation due to the frustration she felt in not being able to create major changes in student achievement or to raise the school’s performance on standardized tests, which remained around 50% below the district’s mean. Burney decried the limited resources Philadelphia schools receive in comparison with their suburban neighbors.

‘My ZIP code shouldn’t determine my education’

Twenty years later, the fates of Stanton and 23 other schools were on the line. They would be sealed in 2013 at a pivotal March hearing of the School Reform Commission, which the state established to stabilize the district’s finances. Its five members — three appointed by the governor and two by the mayor — essentially replaced the locally-controlled school board.

The hearing took place at the school district’s headquarters in Center City before a room packed with hundreds of students, parents, teachers, and activists calling on members of the commission to find some way, any way, to close a gaping budget hole – without closing schools. They carried signs: “Banks got bailed out, Schools got sold out!” and “My ZIP code shouldn’t determine my education!”

The commission had an unenviable task. Pennsylvania schools had been grappling with declining state funding for decades: In 1975, the state provided 55% of public school funding but by 2001 it provided less than 36%. The district had been under the control of the commission since 2001, and was staring at a deficit of $1.35 billion for the 2013-2014 school year, the result of cuts that then-Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Corbett made to the state’s education budget.

Boston Consulting Group, a global management consulting firm hired to find cuts, recommended combining 20 school communities and closing another 24 as part of a five-year plan to make the district more financially stable. The lowered maintenance costs and revenue from selling the buildings would allow the district to save more than $100 million, according to the firm’s analysis.

But residents served by the schools had other ideas. “This is a fiasco! The whole city needs to be shut down!” yelled neighborhood activist Pamela Williams, according to accounts published at the time by WHYY and The Public School Notebook.

Their pleas were largely ignored. By the end of the grueling session, the commission had voted to close 23 schools. The decision to close M. Hall Stanton Elementary came weeks later. The district had already closed a half dozen schools in 2012, so in all, from 2012 to 2014, the district closed 30 schools — 10% of all schools in the district.

It was part of a national trend in which unelected bodies were given power over big-city school districts that were struggling to bring in enough revenue to adequately fund public education for student bodies with high poverty rates and needs.

“It happened everywhere,” said Lisa Haver, cofounder of the Alliance for Philadelphia Public Schools, a grassroots advocacy organization that fought the closings. “It was D.C. It was Chicago. It was every major school district that followed the same pattern of either getting rid of a school board or in some way disempowering a school board.”

Cutting district budgets and closing schools was seen by policymakers through the lens of fiscal discipline and efficiency, and few expressed concerns about the potential impact on community stability and crime. Some advocates did, however.

At a hearing on the proposed closings, Mary Laver spoke on behalf of St. Vincent de Paul Parish, a Germantown Catholic church, to oppose the closing of Robert Fulton Elementary School.

“We are very concerned that a shutdown of Fulton, combined with a shutdown of Germantown and Roosevelt, will put the entire neighborhood at risk,” Laver said, according to The Public School Notebook. “The neighborhood will be deprived of anchor institutions that have stabilized the neighborhood for years.” She predicted an increase in crime.

This pattern of disinvestment in urban communities extended beyond school funding, and it had a serious cumulative impact, Philadelphia City Councilmember Kendra Brooks told MindSite News.

“There was a threat of closing libraries, and resources being drained from Park and Rec programs, and other out-of-school time programs,” Brooks said. “So, what do you expect a generation of people to do without adequate resources to move forward? Right now, I feel like we’re living the results of that.”

But it was the school closings, in her view, that had the biggest impact.

“The population of young people that are on both sides of gun violence — meaning the folks that are being murdered and killed, and the people that are doing the crimes — they will all have been in school during that time where we were closing buildings,” Brooks said.

Losing the ‘village’

Dana Carter spent 16 years as a teacher in the Philadelphia schools, rising to the level of a school-based teacher leader. In 2013 she decided to step away and take a two-year teaching contract in the United Arab Emirates.

When she returned to the U.S. in 2015, she noticed some ominous changes. In the areas where schools had closed, she said, the sense of community no longer existed. “Prior to the school closures, we had a little bit of the village in the community,” Carter said. “The children went to school in the community and the community was able to see what was going on. And now these buildings have become abandoned.”

Schools like George Wharton Pepper Middle School in Southwest Philly, she said, “have become areas of blight with rodents, and trash dumping has been really bad there.” Buildings that were once the pride of the community were now “an eyesore.”

She also noticed that the city’s gun violence numbers were rising, and she began to wonder if there was a correlation. Could the school closings — coupled with other forms of community disinvestment — be contributing to an increase in crime and gun violence?

When gun violence spiked in 2020, she set to work. Using statistics from a Pew research study, the FBI’s Uniform Crime Statistics, unemployment data and information from the school district, she found that the percentage of shootings involving youth had begun climbing in 2013 — the same year Stanton school was closed.

“I was just trying to figure out what the catalyst was to this influx of violence in the streets,” she said.

In December 2021, Carter sent a summary of her findings to the Philadelphia Board of Education. She contended that the combination of disinvestment in neighborhood schools and forcing students to travel to other parts of the city to attend classes was contributing to the rising violence. She asked the district to halt new initiatives that weren’t related to the social and emotional health of students and staff. Those areas, Carter suggested, should be the top priorities for how the district should invest scarce funds.

Carter’s research was ignored.

Will history repeat itself?

Now the district is preparing to embark on another round of closings.

District officials have yet to say how many buildings they seek to close in this round, but they released data showing that 65 are less than half full. Beyond how full a school is, the district has promised to look at the physical condition of the building, the school’s ability to meet students’ needs, and neighborhood vulnerability.

That last factor will look at poverty in the surrounding neighborhood and whether the area was hit by past closings.

For those that are shut down, what will it mean for the neighborhoods they serve?

Advocates say the 2013 round of school closings offer some lessons – and reasons to worry that additional closures will harm the surrounding neighborhoods.

In the case of the M. H. Stanton School, the number of gun-violence incidents had been on the decline prior to its closure in 2013. But in 2015 and 2016, shortly after the school closed, the number of shootings within 500 yards of the school rose quickly, even at a time when citywide gun violence incidents were stable or improving.

Since schools serve neighborhoods in many ways, closing them can pack a serious blow, especially in neighborhoods that have already been harmed by other forms of disinvestment, said Akira Drake Rodriguez, an assistant professor of city planning at the University of Pennsylvania.

Even schools that don’t achieve high test scores and that grapple with other problems still provide a familiar touchstone for children, she noted.

“For some students, school is the safest and most consistent space they have in their lives,” Rodriguez said.

The pandemic put a spotlight on gun violence in Philadelphia

A review of police department data suggests that huge global events like the COVID-19 pandemic and local events like school closings both have an impact on student morale – and in some cases, on gun violence.

Before the COVID-19 shutdowns began in 2020, gun violence had already been rising in Philadelphia. With the massive disruptions to daily life, homicides spiked around the country. In Philly, they rose from 356 in 2019 to 499 in 2020 and 562 in 2021, according to the Philadelphia Police Department.

By the time the pandemic lockdowns ended in 2022, the number of homicides had dipped back down to 516. In both periods, the victims tended to be young, Black and Latino men between 18 and 35 who’d had previous interactions with the law, according to the department.

Student performance also suffered before the pandemic, with one 2019 study suggesting that those “who struggled most academically during this tumultuous time were those attending schools that received the most displaced students,” according to a report by WHYY.

While the pandemic-era increase in gun violence parallels national trends, Councilmember Kendra Brooks believes disinvestment, including the 2012-2013 round of school closings in North Philadelphia and other underserved parts of the city, helped set the stage for the rise in gun violence in the years that followed.Now the district is preparing for another round of school closings and has promised a more community-centered process this time.

A decade later, six schools remain empty

From a distance, the former Fairhill Elementary School looks like one of the city’s many abandoned warehouses. One of at least six schools that still remains empty after being shuttered more than a decade ago, it is located at 6th Street and West Somerset in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood, less than two miles from the Stanton/KIPP site.

Alongside a fence and beneath a tree are two chairs that used to occupy someone’s living room, a table, a trash can, and a recycling bin. The space is decorated with Puerto Rican flags and other mementos. A painted-on hopscotch court and chalk drawings can still be seen — the remnants of a time when students used to play here.

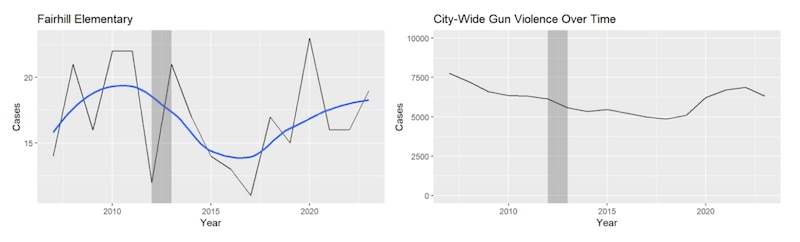

Fairhill is one of the closed schools with no clear pattern of gun violence after closing. For the first two years after it closed, gun violence near the school dipped. Then it began to rise just before a citywide increase in incidents that struck Philadelphia leading up to and during the pandemic.

During a visit last year, a group of men standing underneath a tree in the parking lot warned a reporter to be careful about going to the other side of the building because homeless people using drugs call that space home.

“I’ve been here since 1975,” said one man who preferred not to give his name. “I’ve seen the good, the bad, and the ugly.”

Helping young people avoid the ugly was one of the reasons why Orlando Rosa opened the Pivott Boxing Academy across the street from Fairhill on North 6th Street. The gym trains professional and amateur boxers and has won several awards from USA Boxing, the federation that governs the sport.

Rosa grew up in this neighborhood. While there have always been challenges in this section of the city, the closing of Fairhill Elementary took it to another level and “hurt the neighborhood,” he said.

“The kids have to travel now and they’re not able to go to school in their community,” Rosa added. “They have to go to another neighborhood and it’s difficult to learn when you have to adjust, and you don’t know anyone.”

Other closed school buildings were sold and repurposed. Some, like Stanton, became charter schools. Others such as Germantown High School were redeveloped into housing.

Closing schools can erode neighborhoods, removing hubs that once anchored people and changing their relationship to the neighborhood. Some may sell their homes — in some cases for lower prices due to declines in property values that often come with school closings, Rodriguez, the professor of city planning, said. And that, in turn, can set the table for future losses.

“When these schools close, it really destabilizes the neighborhood, which then can create the conditions for gentrification,” she said.

Edward Bok Technical High School in South Philadelphia, for example, has become a maker space — the Bok Building — with a rooftop bar. At night, affluent patrons of the Bok Bar can have a beer with some Sweet Amalia oysters and look out over the twinkling lights of the Center City skyline.

What can be done about school closings and gun violence in Philadelphia?

While the Philadelphia school district says it will take into account which neighborhoods have already been hurt by school closings — or might have heightened vulnerability in the event of a closing — officials have haven’t yet released information about which schools may be on the chopping block and what steps the district might take to mitigate neighborhood impacts.

Every school that gets closed won’t experience worsening gun violence afterward. But since many of the 30 schools shuttered back in the 2010s did, it makes sense to take into account which neighborhoods are already experiencing high levels of violence when decisions on closures are made, while also taking steps to try and reduce gun violence around the next schools to be shuttered.

The Blueprint for a Safer Philadelphia created by the City Council calls for early interventions like trauma-informed counseling in schools, more access to parks and recreation facilities, conflict resolution training and funding summer school. Ensuring students displaced by the closures have access to these supports could make a difference.

Similarly, the city’s Anti-Violence Community Partnership Grants were credited with helping to fuel the significant decline in homicides since the peak in 2021. Could future grant cycles prioritize at-risk neighborhoods looking to counter the destabilizing effects of losing a neighborhood school?

Rev. Greg Holston, a pastor and anti-violence activist who spent four years as senior adviser on policy and advocacy to the Philadelphia district attorney’s office, believes such investments could make a huge difference.

“With that level of investment, from September of 2020, to until the end of 2023, we had a 31% decrease in gun violence,” Holston said. “We saw the kind of decrease that happens when you put real investment in the community. So that’s the key. When you take schools out, you take investment out and violence goes up because that also impacts the business corridors, the recreation centers, and the libraries. When you put it back in, the violence goes down.”

Data analysis for this story was led by Julie Christie. Reporting for the story was supported by the van Ameringen Foundation and the Commonwealth Fund.