Sign up for Chalkbeat Philadelphia’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system.

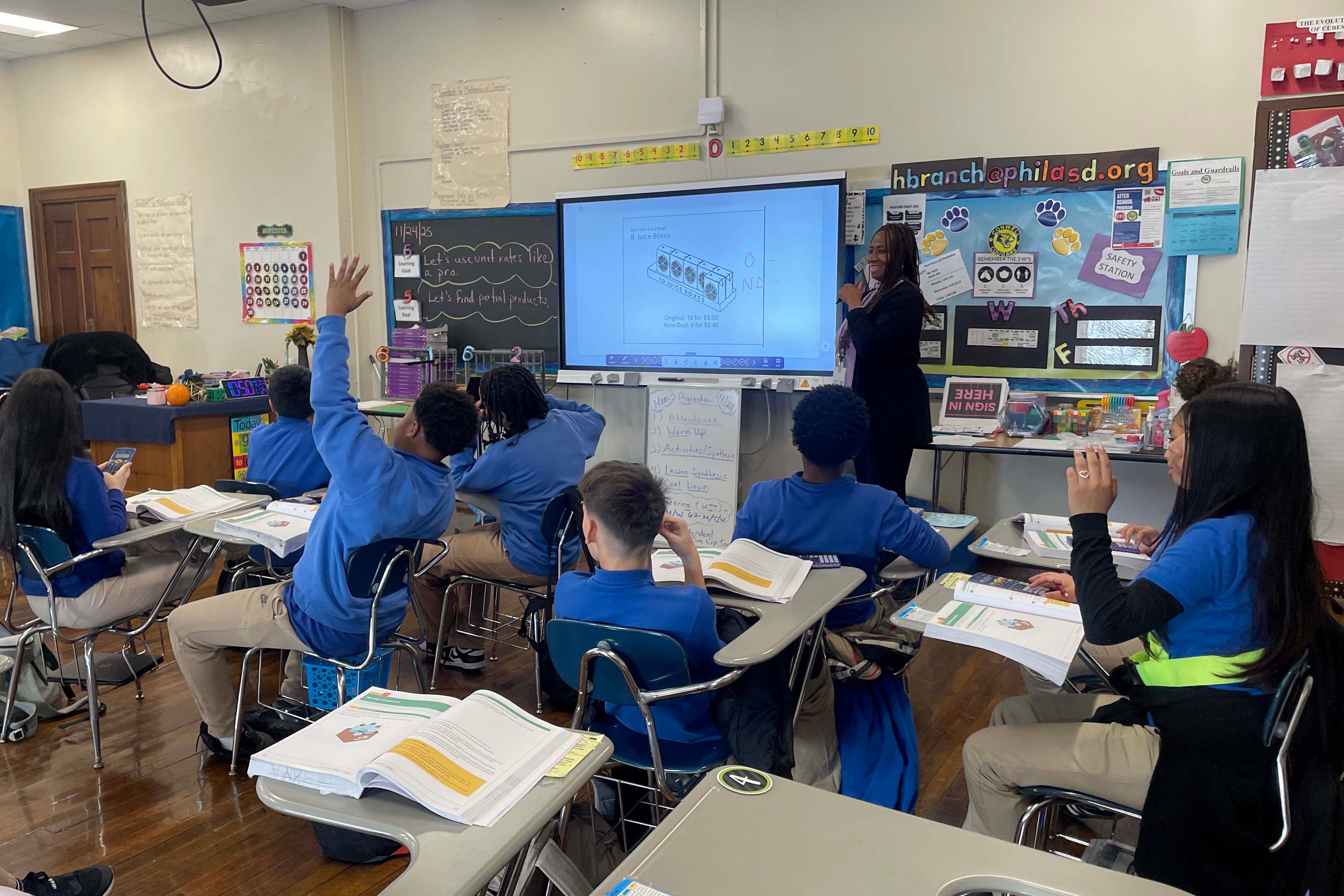

In a third floor classroom at Russell Conwell Middle School in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood, brightly colored math posters hang from the walls and a lengthy description of equivalent ratios covers the white board.

This is what Principal Erica Green calls the HIT classroom — short for high-impact tutoring — where students go for extra help multiple times a week. Around a quarter of the school’s sixth, seventh, and eighth graders participate, Green said.

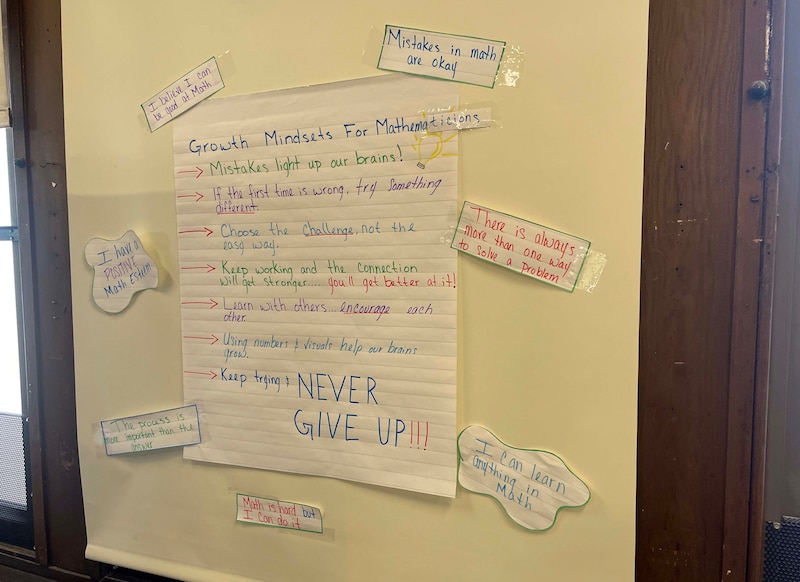

“They’re getting what they need right here at school to boost their learning and math confidence,” said Green. “We’re seeing more student discourse in the classroom, conversations, them challenging and debating with one another.”

Building students’ math comfort and skills is a major aim of the district’s high-impact tutoring program, which provides support to select students integrated into the school day. The district has hired 65 part-time tutors and plans to spend $6.4 million on tutoring programs from two providers, Saga and Littera, over three years to make a real difference for Philadelphia students, who for decades have lagged far behind average statewide scores on annual tests.

At one point, high-impact tutoring, also known as high-dosage tutoring, looked like one of the most effective academic interventions. One analysis of nearly 100 studies on tutoring programs from 2020 found tutoring programs had “consistent and substantial positive impacts.” The Biden administration subsequently urged schools to invest in high-dosage tutoring, and many did.

But in recent months, confidence in tutoring’s promise has deflated somewhat. A recent University of Chicago study of large-scale tutoring programs found that on average, tutoring programs during the 2023-24 school year only resulted in one or two months of extra learning for students. The researchers found that at many schools, logistical hurdles led to students receiving far less tutoring than what they would need to reap the full benefits.

“We see actually in the data that tutoring is effective,” said John Wolf, associate director for the University of Chicago Education Lab, which conducted the recent study. “It’s just that you need enough time to get at it.”

These are the lessons Philadelphia is trying to heed as it invests more in tutoring and tries to overcome the barriers that other districts have confronted: scheduling, tutoring training, and aligning tutoring content with curriculum.

Philadelphia officials say they’re following the research, scheduling at least 90 minutes of tutoring per week, and tracking participation through its tutoring providers.

“We’re looking for results,” said Nyshawana Francis-Thompson, the district’s chief of curriculum and instruction. “We are really looking for this to make a significant impact on student achievement.”

So far, the district has seen some promising outcomes. Last school year, nearly half of students that received high-impact tutoring showed a faster rate of progress on district benchmark tests compared with the previous year. That aligns with Superintendent Tony Watlington’s goal of making the district the “fastest-improving large, urban school district in the country.”

But still, only around 600 students at 20 schools get high-impact tutoring — a drop in the bucket for the 120,000-student district. And at some schools with tutoring programs, like Conwell, state test scores continue to decline even though teachers and students say the program is useful.

Francis-Thompson said she wants the district to expand high-impact tutoring to more schools and students. But to do so, it’ll have to train up enough tutors, pay for larger contracts with tutoring program providers, and overcome other challenges.

“There’s a need for additional funding to support this type of work and any type of expansion,” said Francis-Thompson.

Teachers say tutoring boosts learning, but test scores lag

Conwell Middle School selects students for tutoring based largely on their teachers’ recommendations and test scores. It also considers whether a parent or a student displays interest in the program, said Green, the principal.

The school’s tutoring setup largely follows the research, scheduling kids for a total of around 120 minutes of math tutoring each week. Most days except Fridays, students go to tutoring for the last 30 minutes of their daily math block, after instructional time is over.

Tutors aren’t solely focused on helping kids with homework or redoing class assignments. Instead, in small groups of three or four students, they teach content that builds on what the students have already learned in class. They’re also in touch with the school’s math teachers to make sure the tutoring curriculum follows what’s happening in class.

Tutor Rebecca Resch said she has heard from tutors at other schools that communication between tutors, teachers, and administrators within some buildings can be tricky. But at Conwell, Resch said, “they want us here, they want us to help out.”

Conwell math teacher Audrey Golub has seen the positive impact in class. At times, students have told her they’re familiar with a concept she’s teaching because they’ve learned about it already in tutoring.

“That’s the most amazing thing,” she said. “Because if they’re recognizing the work we do in [class], because they’re being supported by tutoring, then we are working together, hand in hand, to make and reach that achievement.”

Still, tutoring is no magic bullet. Data that Green shared from the school’s progress screeners that take place during the year, called Star Assessments, show that over the course of last school year, the first full year of the tutoring program, Conwell students’ math scores improved.

But over the last two years, the percentage of Conwell students scoring proficient on state tests has declined. Last year, only 8% of students achieved proficient scores on the state math test. Around a quarter of the district’s students in grades K-8 achieved proficient scores.

Beyond test scores, Conwell teachers said they’ve witnessed other benefits of the program.

“I’m seeing that they seem more enthusiastic, especially some of them that I could tell already had fears about math,” said math teacher Hytolia Branch. “They’re starting to become more comfortable.”

More tutoring time drives better results, researchers say

Philly is far from the only district looking to high-impact tutoring to boost achievement. Since tutoring programs boomed after the pandemic with the help of federal COVID relief dollars, districts across the country have looked to implement research-backed tutoring methods into schools.

High-impact tutoring has emerged as one form that researchers have shown actually works — when done well.

Stanford University researchers have found that high-impact tutoring works when it is embedded into the school day, happens at least three times per week in small groups, and matches the same tutors with students as much as possible. The Stanford researchers also found that tutoring is most effective when schools use data to identify students’ needs, and when tutoring materials align with research-backed and state standards.

At the University Chicago, Wolf and other researchers have found that the amount of time students get for tutoring is strongly related to how much they’ll benefit. More time, Wolf said, almost always leads to more learning gains. Yet districts often struggle to fit tutoring time into already-busy school schedules. And tracking which students are going to tutoring presents more difficulties, Wolf said.

“It’s one of the most promising academic instructional vehicles that we have seen,” he said. “The big question is, how do districts build it into part and parcel of how they provide instructions to students, so that students can get enough of it to benefit?”

There’s a lot of pressure on any academic intervention to show results. Philadelphia’s math and reading scores on a national assessment are largely behind where they were a decade ago. But for some students, the tutoring program is already making a difference.

Conwell sixth grader Mia said she used to get poor grades in math class. But since joining the tutoring program, she’s improved. Now, she said, tutoring makes her feel “happy.”

“Sometimes people struggle in math, and that’s something that I do a lot,” said Mia. “They give me a little bit of extra help so I could participate more in class and learn more.”

Rebecca Redelmeier is a reporter at Chalkbeat Philadelphia. She writes about public schools, early childhood education, and issues that affect students, families, and educators across Philadelphia. Contact Rebecca at rredelmeier@chalkbeat.org.