As most Memphis students sort through paper lesson packets or tune in to televised lessons, several charter schools have already switched to online learning.

The quicker adjustment highlights the nimble nature of charter schools that oversee far fewer students than Shelby County Schools. The district’s 57 charter schools with more than 18,000 students comprise just 16% of the overall enrollment.

But the city’s charter schools, like the traditional public schools, still face steep challenges to get students learning remotely in one of the poorest large cities in the nation with one of the lowest rates of internet connectivity.

Few, if any, Memphis charter schools are using online assignments to calculate grades, though teachers are providing feedback on the work. The State Board of Education’s emergency rules passed last month prohibit schools from lowering students’ grades based on work done while school is out, although they can be used to improve their grades.

Here’s what online learning looked like during three weeks in April at three Memphis charter schools:

Freedom Preparatory Academy: Rapid-fire lessons in big groups

Jenice Davis, a seventh-grade teacher at Freedom Preparatory Academy, is juggling a lot. She has been calling her students three times a week to check in on them, coordinating teachers across social studies and English to work on online lessons, and helping her own daughter, a kindergartner, keep up with learning. It’s constant communication and troubleshooting between students, parents, and teachers on various online tools like Google Classroom, Flipgrid, and Zoom.

Davis assured students her first priority is to connect with them and their families to make sure they’re OK. The charter network set up an emergency fund for families who lost their jobs because of the pandemic. And a new perk for students who rack up the most participation, good behavior, and correct answers: pizza delivery for their family.

But when school was in session during videoconferencing, it was down to business. About 50 seventh-grade students and eight teachers joined from their living rooms, bedrooms, and kitchen tables. The occasional younger sibling popped up in the corner of the screen to see what was going on.

Davis and her fellow teachers recognized students were thinking a lot about the coronavirus and its impact on their families and the larger community. So, they chose a lesson on comparing photos of Los Angeles’ smog-filled skyline in 1998 and a clearer photo last month to talk about how the coronavirus and stay-at-home orders unexpectedly benefitted air quality in the polluted city. They also read and discussed poems that contrast the calmness of nature amid previous pandemics.

During this session in mid-April, Davis was not leading a class, but helped facilitate small group discussions. At the end of the 30-minute lesson, she and the rest of the English and social studies teachers cycled off and a group of math and science teachers joined the call. The entire 90-minute session allowed students to take three classes, including an elective such as book club or art.

Soon after online classes started at the end of March, Davis noticed that many students had their video feed turned off. When she talked to her school’s counselor about it, she said Davis shouldn’t pressure the students to turn on their cameras. Though some students may have kept the camera off so the teacher wouldn’t see them tuning out, others may have been embarrassed.

But many students still participated in discussions.

“It’s exciting because you get to see their faces, but you also have those moments when you realize the living space of students,” most of whom live in poverty, Davis said. “So, reality kind of settles in.”

Crosstown High School: Few online classes, more independent work

Lily Smith, a sophomore at Crosstown High School, is quick to admit she — like many of her classmates — wakes up 10 minutes or less before her morning check-in with a teacher and about a dozen classmates.

She likes the newfound flexibility and short commute from her bed to her desk — unless she stopped by the kitchen first for some waffles to eat during class. The check-in, known as advisory group, is a less formal class meant to build a sense of community among students.

It’s the only time Crosstown High students have a live online class. Even before the pandemic, the school’s leaders encouraged teachers to guide students, rather than lecture them. So, if a student has a question on an assignment, teachers are available for virtual office hours, but no individual classes on specific subjects are held.

Sara Grisanti, a sophomore, confessed she misses the live interaction.

“I like school better than online school,” she said. “You have to wait for a certain time to get help. Before if I needed help, someone was right there.”

Without the live lessons, algebra teacher Shelley Cox rarely sees her students who aren’t in her advisory group.

“I think about my students a lot. I really miss them,” she said.

As Cox waited to start the advisory group one morning in early April, she told her students to call or text their missing classmates and remind them to log on. Some joined on a laptop and kept an eye on their smartphone nearby. That’s on top of the tablets Crosstown provided to each of its 280 students. Unlike most Memphis charter schools, there are fewer students from low-income families.

Cox started class with an update: Teachers were planning to host more video sessions for students. They had been complaining they were bored and wanted to see each other more often — one student mentioned he briefly thought about shaving off his eyebrows to satisfy his boredom. Cox was considering sharing baking tips and recipes, and other teachers wanted to focus on students becoming lawyers and exploring other possible careers.

Before the coronavirus crisis, Cox had prompted the group to take turns sharing a hobby or talent to get to know each other better. To continue the routine, two students performed a rap to brag on their advisory group. They were met with thunderous applause — just as soon as Cox unmuted their microphones.

Gestalt Community Schools: Similar to the school day, but simpler

Austin, a kindergarten student at Gestalt Community Schools, was attentive and didn’t leave his seat for most of the online class until he asked his teacher if he could go to the bathroom. His teacher, Candace Hill, stifled a chuckle and gave him permission to go — something that would have been normal in a classroom but seemed out of place during a video call from home.

Hill was surrounded by charts and props to keep the attention of the 5-year-olds. During this videoconference in late April, which lasted about 45 minutes, just three of her 19 students were present. Participation had been spotty as leaders across the network’s five schools sought to connect families with laptops and internet access for nearly 2,300 students.

During a review game of “tricky” sight words on flash cards, Austin tapped a finger on his temple to signal that he disagreed with his classmate about a word.

“Ms. Hill that’s from,” not four, he said. He was right.

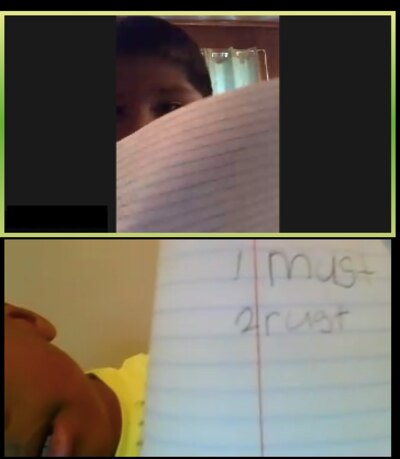

In the next exercise, Hill read a word out loud for them to write down on their papers. Then she asked them to hold their notebooks up to the camera so she could check their spelling. Austin and his classmates needed a little prompting to make sure their answer actually showed up on the camera’s range, but they adapted and needed fewer directions the next time.

Austin did a few jumping jacks along with his other classmates. Then they all took turns reading a short story on the teacher’s screen about a boy who had chores to do around the house. When one student stumbled on a word, the teacher highlighted it on her screen and Austin helped him out by reading the word out loud.

Hill’s goal, along with other elementary teachers, is to check in by phone with each student outside of class. Elementary school students like Austin, who are in the middle of some of the most critical lessons in building reading skills, pose a particular challenge for online learning even if the family has internet access, because students need adult help to log on.

“It’s really about making sure, not just that we do the virtual part, but more so connecting with families on the daily,” said Bobbie Turner, the network’s chief academic officer.