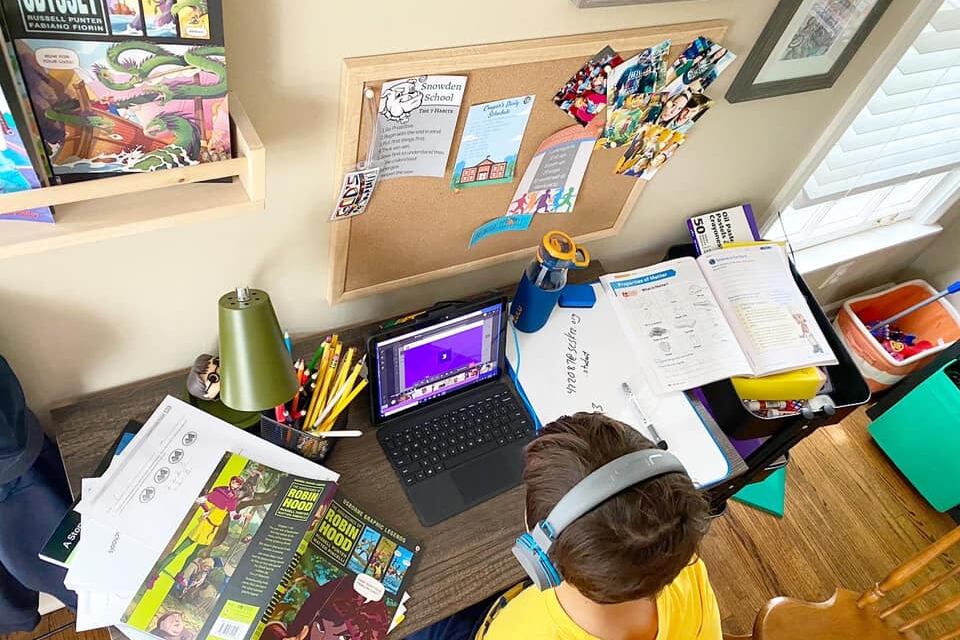

Three weeks into the school year, Sara Corum’s two sons, Cooper and Aiden Tate, had finally gotten into a solid routine after all the upheaval COVID caused over the last two years in Memphis schools. Then, the family’s world was turned upside down — again — when they got “the call.”

Cooper, a fourth grader at Snowden School, was a close contact of a fellow student who tested positive for the virus. Neither Cooper nor Aiden, a second grader, was exhibiting symptoms, but they were required to stay home and quarantine for the next two weeks.

What came next was chaos, Corum said. The boys’ teachers had not been informed by administrators or local health officials that they were in quarantine and would miss the next 10 school days, she said. Although a state board of education rule says teachers are not permitted to teach students in quarantine, the district has said quarantined students will receive “virtual asynchronous learning.” But Corum said no virtual instruction was provided, and the little schoolwork they did receive came with few directions.

Her family’s experience is just one example of the mayhem quarantines have caused for thousands of Memphis families and educators two months into the school year. Some parents say they are increasingly frustrated with Shelby County School administrators, complaining of poor communication, dissatisfaction with the instruction quarantined students receive, and a lack of access to learning devices and hot spots that the district previously provided.

Districtwide, 3,381 students and 523 staff members had contracted COVID as of Thursday, according to the SCS dashboard, meaning that since August, thousands of students and staff who were close contacts have likely had to quarantine.

Shelby County Schools spokesperson Jerica Phillips said administrators and educators continue to pivot and make improvements. She asked families for patience while the district serves the majority of the district’s more than 110,000 students in person.

“This is just beyond the scope of work that we’ve ever had to do,” Phillips said, “so we understand there’ll be frustrations among parents and we just ask for grace as we continue to do this work.”

Although they know the district is limited by the state’s virtual learning restrictions and operating a school system during a pandemic is challenging, many parents still say they wish the district’s quarantine instruction was better.

Schoolwork provided to children in quarantine varies between teachers, Phillips said. In some cases, a quarantined student’s teacher may also be in quarantine, Phillips said, and a substitute teacher may not know how to use the district’s distance learning platforms.

She emphasized that quarantine learning is meant to be “supplemental,” and like a sick day, any makeup work given won’t completely replace instruction given in a classroom.

“There is no one size fits all when it comes to asynchronous learning,” Phillips said. “We don’t want families to get discouraged about what that looks like. We just want to ensure some continuing learning.”

Many parents don’t feel it’s safe to send their children to school at all, and wish the district would have started the year with an online option amid the delta surge — even if it meant defying state orders.

“It felt like things were going well, then we had the rug pulled out from under us,” Corum said.

She and husband Josh McClurkan juggled their jobs as pastors while becoming makeshift quarantine tutors. “We’re not teachers. We’re not equipped, Lord have mercy, to teach our own kids.

“And now, honestly, I’m just waiting for it to happen again.”

The quarantine obstacles aren’t new this year. In a state educator survey, 65% of responding educators who taught in person last year said adapting to mandated student and staff quarantines was a challenge. And 40% of the teachers who responded said quarantine was the biggest challenge they faced.

In the survey, in-person teachers also listed student absenteeism as their largest worry. According to Memphis schools policy, students who are unvaccinated and come in close contact with a student or a staff member who tests positive must quarantine and monitor for symptoms for 10 days after exposure. Fully vaccinated students, meanwhile, are not required to quarantine.

Districts across the country have started relaxing quarantine restrictions due to concerns about keeping students out of school for weeks on end, as well as growing evidence that other safety measures can successfully prevent the spread of COVID. In New York City unvaccinated students who are masked and follow social distancing guidelines no longer have to quarantine if they’re a close contact. Philadelphia, Colorado, and Indiana have also loosened quarantines.

In Memphis, COVID anxiety remains high, even though the spike in cases caused by the delta variant in recent months is easing.

Although ShaRae Hicks has not gotten notice to quarantine any of her three children — a fifth grader at Ford Road Elementary School and two students at Hillcrest High School — she worries about why they haven’t. She figures it’s impossible that they have never been in close contact with a positive case, given the number of text, email, and robocall notifications she’s received from the school about positive cases. Hicks wishes she had the ability to choose entirely online learning for her children.

When the district “makes these robocalls saying that someone tested positive, you don’t know if it’s someone they were near. You don’t know if it’s a child or if it’s a teacher. You don’t know if it’s an administrator,” Hicks said. “You just don’t know. And that’s stressful and brings about a lot of anxiety.”

On the other hand, Hicks worries about what would happen if her children were forced to quarantine. After moving to a different neighborhood and switching schools this year, they still don’t have district-provided tablets, laptops, or hotspots to use at home, she said.

Because of the move, Hicks said, the district asked her children to return the devices issued to them last school year for virtual learning — with the promise they would receive new devices from their new school at the start of the year.

Nearly two months into the school year, the Hicks have yet to receive them.

Phillips said she’s aware of individual cases where families have not yet received hotspots, but principals and administrators are working as hard as they can to find those families and distribute devices to them.

While they recently got Wi-Fi at their home, Hicks can’t afford to buy another device for them to use.

“It’s really been a strain on my family,” she said.

Like Hicks, Malica Hanesh worries about what she doesn’t hear about COVID cases from the district. Hanesh said she never got a notification from White Station High School or the district that her daughter had been near a student with COVID, even though she had been. Within a week of that close contact, her daughter tested positive.

“I’m just ticked off at the lackadaisical attitude of the school and district concerning the health impacts that this virus causes,” Hanesh said, saying communication has been “poor.”

The district’s newly expanded contact tracing team follows guidelines from the Shelby County Health Department and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to determine close contacts, said Dr. Patricia Bafford, the district’s senior manager of health services.

Under that guidance, Bafford said, anyone who came within 3 feet of a positive case for 15 minutes or longer, whether they wore a mask or not, would be considered a close contact. District contact tracers use seating charts to make such decisions, Bafford said, and from there, a team of nurses makes calls to tell those affected to quarantine and for how long.

In an effort to be transparent, the district also informs all students, staff, and parents of all positive cases in their school via robocalls, Phillips said. The district doesn’t disclose who tested positive — even to students’ teachers — in an effort to maintain some privacy.

The district wouldn’t tell Chalkbeat how many students or staff have been in quarantine since the school year began, or how many classrooms have been affected, citing privacy concerns.

Phillips said district officials are continuing efforts to improve communication with families, from the way it contacts families about COVID cases and quarantines to providing COVID updates publicly on the district website. And, Phillips said, the district has held numerous public family forums to encourage feedback and resolve issues individual families are having.

“Our school leaders are doing their very best to adjust as needed and make sure all protocols are being followed,” Phillips said.

Despite these efforts, frustration remains.

In Veronica Jones’ 40 years, she’s never been as frightened as she was when her two daughters, ages 8 and 10, became infected with COVID in late August after she believes they were exposed at school. Symptoms that mirrored the common cold quickly escalated and Jones had to take the girls to the hospital.

Jones, who also helps care for her grandchildren, had to take unpaid time off of her job at a Memphis hospital while her daughters were sick.

“As a mother, seeing my girls in such pain broke me all the way down,” Jones said. “Somebody has to do something. I’m just praying. That’s all I can do.”

Although Jones appreciated that her daughters’ teachers at Frayser-Coming Achievement Elementary were understanding about academic expectations while they were sick, she was frustrated that her daughters were given a printed packet of lessons.

More than ever, Jones wishes Tennessee parents had more virtual learning options.

After four weeks, the girls recovered and had returned to their charter school. But weeks later, just before the district started fall break, Jones’ daughters were back in quarantine after another exposure, and Jones was back at home without pay.