Even on the eve of Randy Butler’s return to school, the fifth grader’s parents weren’t sure if they were making the right decision, he said. But as he connected with peers and met his teacher in person Monday for the first time since online classes started in August, he was excited.

“It’s a happy reunion, basically,” said Randy, who attends Riverwood Elementary. After months of his younger siblings interrupting his classes and wearing a mask and social distancing at the grocery store with his family, he was ready to be back in a classroom.

“It’s definitely a lot easier to focus,” he said.

Randy was one of more than 17,000 elementary students, about a third, expected to return to Shelby County Schools classrooms Monday. About a fourth of middle and high school students are scheduled to return March 8. Most parents opted to keep their children learning remotely. School buildings in the Memphis district have been closed to students since the pandemic hit the city a year ago. Shelby County Schools was the last district in Tennessee to reopen classrooms.

When Superintendent Joris Ray unveiled his initial reopening plans last summer, teachers could choose to work remotely. He delayed the plans as COVID-19 devastated the community. But after state lawmakers threatened to cut funding if the district did not offer in-person learning and the virus’ spread started to recede, Ray two weeks ago announced he would require teachers to return to classrooms.

Still, Ray did not get as much pushback from the district’s 6,500 teachers as other cities across the nation did about returning to classrooms. But unions in Tennessee also have little power to challenge district actions after state lawmakers stripped them of bargaining rights a decade ago.

“The teachers, them returning in person, just did my heart glad,” Ray told reporters Monday afternoon. “So far, so good. We’ve had a great day.”

Ray said the public should expect some COVID-19 cases and possible individual school closures like other school systems across the nation have when students or staff have to quarantine. Ray said Shelby County Schools will report all cases to the state so the information will be publicly available by school.

“We’ve done everything we can possibly do, but the virus is still here,” he said.

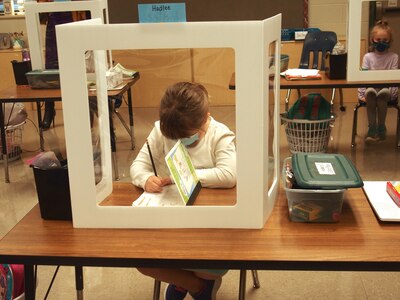

But under the district’s plan, returning to classrooms does not mean a return to traditional in-person learning. All students, whether learning remotely or in a classroom, will continue to log on to live videoconferencing with their teachers.

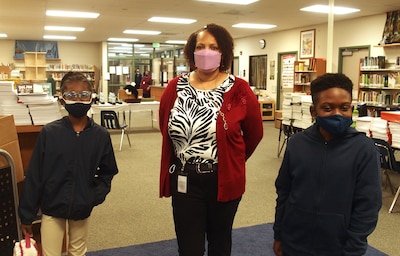

At Riverwood Elementary, the third stop of the day for Ray and his leadership team, about a third of the school’s 919 students were expected to return. Principal Latisha Brown said she was missing about 40 whose parents had signed them up to return.

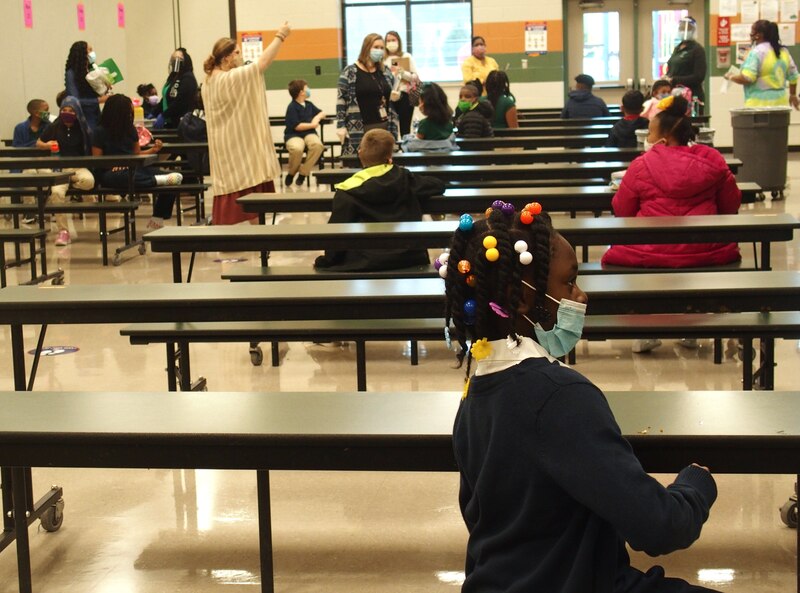

As masked students stopped in the hallways, they looked down to see if they lined up with floor markers set 6 feet apart and backed up when needed. At the entrance of each classroom, there was a table with a large bottle of hand sanitizer. Some had boxes of disinfectant wipes. Inside classrooms, students worked on their tablets with headphones behind mostly clear desk shields. As students rotated through the cafeteria for lunch, each class was assigned a row and spaced out to have two students at each table.

Still, parents and teachers have expressed concern about buildings staying clean, having hot water in bathrooms, and having ample ventilation if windows aren’t operable. A district spokeswoman said Monday that though janitorial staff clean surfaces more frequently and restock paper towels and soap dispensers daily, the district’s vendors have not hired more staff to carry out the increased workload. Some fixes for building ventilation are expected under the district’s next round of federal COVID-19 relief money.

While Monday’s reopening got the most attention, most of the district’s students are still learning remotely. Porsha Holloway has four children at Vollentine Elementary and decided to keep them home. She doesn’t want them to wear masks all day and worries that they could get sick.

“I doubt if [other students] will follow the directions with keeping their hygiene up,” she said. “You got to tell them how to bathe… just to expect them to do it on their own is a lot.”

Holloway stopped taking hair styling clients so she could stay at home with her children during virtual learning because their father works. But she worries her children will be bored as teachers assign more work for students to do on their own. When teachers did this last week, her children finished all their work by Wednesday.

In anticipation of returning to classrooms before Ray’s announcement, Carol Welch, a kindergarten teacher at Riverwood Elementary, drove to neighboring Haywood County about a month ago to get her first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine before it was available locally. On Monday, about half of her class was in the classroom, while the rest were learning remotely. At top of mind for her is making sure that students at home don’t feel left out.

“I’m determined to make it equitable,” she said. She will offer the same materials and activities to students at home that she offers for students in her classroom.

When Jamie Veals, a fifth grade teacher at Whitehaven Elementary, first learned that teachers would be required to return to classrooms, she felt “against a wall” and wasn’t sure how it was going to work out. But once the district arranged for teachers to get their first vaccine doses last week and her principal reviewed safety protocols, she felt better.

“It is not as bad as we think it is. It was actually a lot better,” she said. “If we can follow the guidelines… I believe we will be fine.”

District officials did not reveal how many teachers have quit, received accommodations under federal disability laws, or taken extended leaves since Ray announced the new reopening plan Feb. 12. Ray did say that only 40 of the 300 teachers who are eligible to retire said they would.