Sign up for Chalkbeat Tennessee’s free newsletter to keep up with statewide education policy and Memphis-Shelby County Schools.

After more than a decade of state takeovers and contentious charter conversions, Tennessee is set to shut down the state-run Achievement School District and create a new model of intervention for low-performing schools by the start of the 2026-27 school year.

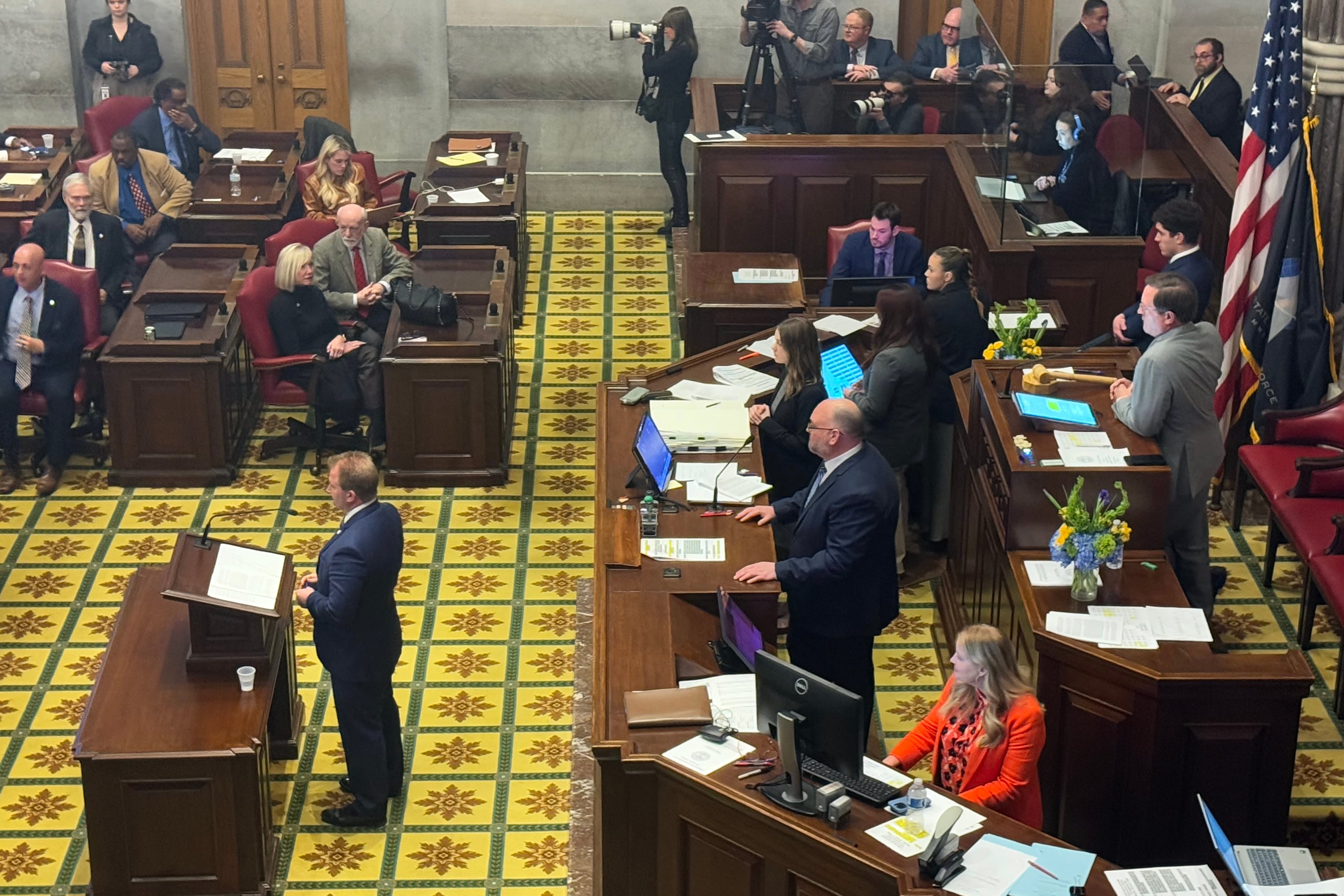

Legislation to replace the failed ASD cleared the House 75-15 on Monday, sending the bill to Gov. Bill Lee, who has indicated his support.

“Tennessee needs a support system for priority schools that contains accountability but also provides school districts more local flexibility in determining which interventions will be most effective,” a Lee spokesperson told Chalkbeat in a statement.

The ASD removed low-performing schools from local control and placed them under a state-run district, with the goal to push Tennessee’s bottom 5% of schools to the top 25%. Many of the schools were turned over to charter operators to run under 10-year contracts.

Research showed the ASD led to high teacher turnover, and did not generate long-term improvements for students. The district also faced community backlash for taking over schools in districts that served mostly low-income communities and predominantly Black student populations. The ASD cost taxpayers over $1 billion. Only three schools remain in the ASD.

The new model creates a tiered system, with escalating levels of intervention for schools that do not academically improve. Schools identified for intervention for the first time would start at the first tier. The Tennessee Department of Education then will review each school’s performance annually to decide whether to change the level of intervention.

Tier 1 would give districts the option to direct their own intervention plans or partner with a turnaround expert.

In Tier 2, districts can choose between conversion to a charter school, transfer of operations to a higher education institution, or the replacement of some or all school leadership and specific staff. There is also the option to implement an intervention committee – made up of school board members, school employees and parents – to develop a plan with a turnaround expert.

Tier 3 involves school closures or replacement of school leadership and instructional staff under the direction of the state department of education.

All strategies would require state approval.

The new model applies to “priority schools” across the state, defined as:

- The bottom 5% of schools in performance. Federal law requires states to intervene in public schools in the bottom 5%.

- All public high schools that fail to graduate one-third or more of their students.

- Schools with chronically low-performing student groups that have not improved after receiving additional support.

Democratic Rep. Antonio Parkinson of Memphis, who has previously brought legislation to end the ASD, celebrated its sunset.

“We finally end this catastrophe of an experiment in education, served on the backs of our communities,” said Parkinson. “Just when we thought the schools couldn’t perform any worse, because they’re at the bottom of the 5%, the Tennessee Achievement School District came and proved us wrong.”

However, he said the bill’s new model was a “remix” of the ASD and cautioned that the legislation could expand charter conversion.

Republican Rep. Debra Moody of Covington, who sponsored the bill, said charter conversion is one option among many that the district could choose.

The legislation now heads to the governor’s desk for signature.