For Claiborne Wade, the week has been a blur of shuttling among the rooms where three of his children learned online and trying to keep them on track. That’s sometimes a tall order for his first grader, whose attention slips away from his teacher occasionally to playing with a pencil or parading his toys for his classmates on screen.

For Chicago families such as Wade’s, the start of the school year this week brought an often hectic return to supervising their children’s learning — but with markedly higher demands than last spring. After an uneven foray into remote learning, Chicago Public Schools called for a six to seven-hour school day this fall, with hours of live video instruction for most students. First graders like Wade’s son, for instance, are expected to spend three hours a day in live classes.

The Chicago Teachers Union and some parents are pushing back against the changes, saying they saddle students with too much screen time and make for a draining school day, especially for younger children. District officials counter that these changes are needed to keep Chicago’s academic momentum going and prevent ceding to the pandemic major gains students have made in recent years.

Some parents said they feel torn: The first days of school have left them overwhelmed and sometimes at a loss for ways to keep students focused on their screens. But they balk at the idea of scaling back requirements.

“It’s a lot. It can be challenging,” Wade said. “But that’s what we need to do until we can go back to the classroom — and then we kick it into overdrive.”

The debate about how far districts should go in trying to replicate a brick-and-mortar day virtually is picking up nationally, where many districts are stepping up online learning’s rigor. Some parents have argued that districts are overcorrecting after a spring of lowering expectations, and have signed petitions to demand a shorter school day. Others say more live teaching, structure and direction from schools makes their role of orchestrating at-home learning a bit easier.

“Chicken with his head cut off”

The first days of the school year meant lots of juggling for parents. LaTeShia Hollingsworth, the mom of four students in pre-kindergarten, fourth, seventh and ninth grade, set up her older children at the dining room table, with their laptops and school supplies at the ready. But, in the course of the school day, the students increasingly gave each other “little mad faces” as live classes overlapped and threatened to drown each other out.

Hollingsworth’s children attend two UChicago Charter campuses on the South Side, where she says virtual school days are also longer and more structured this fall.

So on the second day, each student logged onto classes from separate rooms. That meant Hollingsworth had to dash from room to room to supervise, making sure each child was in the right digital classroom at the right time, before heading off to her part-time job at a daycare.

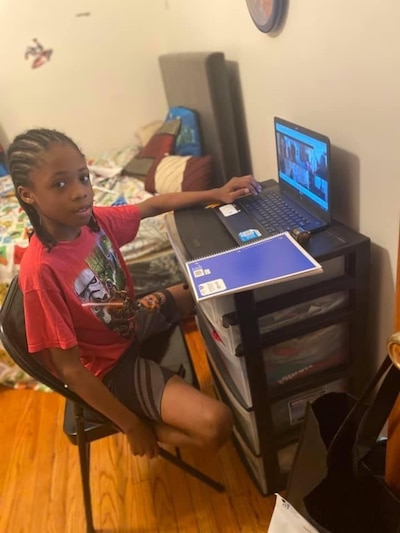

For Wade, the dad of a first and third grader at DePriest Elementary and a fifth grader at G. R. Clark Elementary on the West Side, the hard part was juggling three different schedules, all of which toggled between live classes and time for more independent school work. All the while, Wade, a parent liaison at DePriest, was trying to troubleshoot issues for other families over email.

“Working with all those schedules was really hectic,” he said. “I was running like a chicken with his head cut off.”

The stresses of those first days spilled over onto social media, where some parents said the new virtual days felt way too long, especially in the early grades. As the district resumes taking daily attendance, parents worried their elementary students might get marked absent if they felt they needed to take a break and wander away from their screens. (The district stressed this week students will not be marked absent if they step away from their computers briefly.)

The stress was also evident in a Spanish-language Facebook forum Univision hosted Tuesday, at which parents peppered district officials about resolving technical issues and “battling with all the links” to get into virtual classrooms.

The new virtual day with its more demanding schedule was an adjustment for students, parents said. In the early afternoon on the first day, Hollingsworth’s seventh grader asked her if he could close his laptop, go to his room, and lie down. “No,” she told him. “You are in school.”

By the end of day two, after listening to her fourth-grader’s teacher continually remind students to sit down, turn their cameras on and pay attention, Hollingsworth felt more understanding.

“I felt like closing her laptop and telling her to go and take a rest,” she said. “Sitting there for two or three hours straight in front of the computer, they were getting restless. The energy wasn’t the same.”

Chicago Teachers Union leaders have said the district is trying to squeeze a brick-and-mortar school day into a virtual format, and sometimes the outcome is not developmentally appropriate. At a press event the union hosted on the first day of school, some teachers voiced anxiety about keeping students engaged for lengthy stretches in front of a screen.

District leaders, on the other hand, have said they want to step up the rigor of learning this fall to shore up gains in graduation rates and other metrics the district has made in recent years. They stressed that schedules do blend screen time with independent work away from computers. Illinois issued state guidelines this summer requiring at least a five-hour day and strongly recommending at least two-and-half hours of daily live instruction.

“If teachers have a lesson plan, and a mission and path, students are going to be connected and are going to learn,” Mayor Lori Lightfoot said.

A pendulum swinging

Districts that are kicking off the school year in virtual mode across the country are grappling with how to strike a balance between setting high expectations and keeping the school day manageable. Largely, the pendulum is swinging sharply toward longer days of learning and more live instruction.

A recent study of 477 districts by the Center on Reinventing Public Education, a nonprofit organization based in Seattle, found that many districts pulled back significantly last spring, with only a third of districts requiring any direct instruction or tracking student participation. This fall, at least in the country’s larger cities, “A lot of districts are planning for much more than they provided in the spring,” said Alice Opalka, one of the study’s authors.

Almost 90% of 106 districts the center is tracking explicitly require some live instruction, even if many are not specifying the length of time as Chicago did.

Chicago’s school day is longer and includes more live teaching than some other big urban districts. Los Angeles Unified School District negotiated with its teachers union a school day that runs from 9 a.m. to 2:15 p.m., with at least 90 minutes of live instruction for most students. New York is giving schools more discretion to design their days and cautioning that shorter periods of video instruction might work better for younger learners.

But Chicago is by no means an outlier. Districts from Atlanta to Aurora, Colo., to San Antonio are calling for six-hour school days or longer, in some cases with more stringent live instruction expectations than Chicago’s.

Without much precedent, “We’re seeing a huge range between what districts are offering,” Opalka said, adding that a slew of sometimes conflicting pressures have factored into district decisions, from state mandates to teacher union negotiations to parental input.

She noted some Los Angeles parents have called for more instruction this fall. Meanwhile, in Shelby County Schools in Tennessee, more than 17,000 parents have signed a petition to limit live instruction from 8 a.m. to noon, instead of 3 p.m.

In Chicago, parents said that although breaking up the live screen time with off-screen learning and physical activity can make supervising students more demanding, it does help with screen exhaustion. They commended teachers who actively encourage students to close their laptops and take a break from the screen — and who give them clear, detailed instructions for making the most of their independent learning time.

Some said they appreciated the additional structure and the higher expectations this fall. Last spring, Elvia Herrera’s daughter, a fifth grader at the time, shared her mom’s laptop, catching up on school assignments after Herrera was done with work. The girl, a student at Burrows Elementary on the city’s Southwest Side, now has a district-issued Chromebook, and so far, she has gamely navigated the switch in middle school to multiple teachers and multiple virtual classrooms.

“The fact that it’s a full school day brings more normalcy,” Herrera said. “The school and teachers are doing the best they can in this uncharted territory.”

Gabriela Oria said the school day for her son, an eighth grader at Madero Middle School on the Southwest Side, can feel intense, with its 5-minute breaks between classes. Her child complained that it’s too much. “There’s more work and more responsibility for us as parents as well,” she said. But she said that after worrying last spring that her son was losing too much academic ground amid the disruption, she feels more relaxed now and more confident he is on track to recoup any losses.

Said Hollingsworth, “If you scale back, students are going to be missing so much. They are still trying to play catch up from last year.”