A version of this article first appeared on citybureau.org. Read Here.

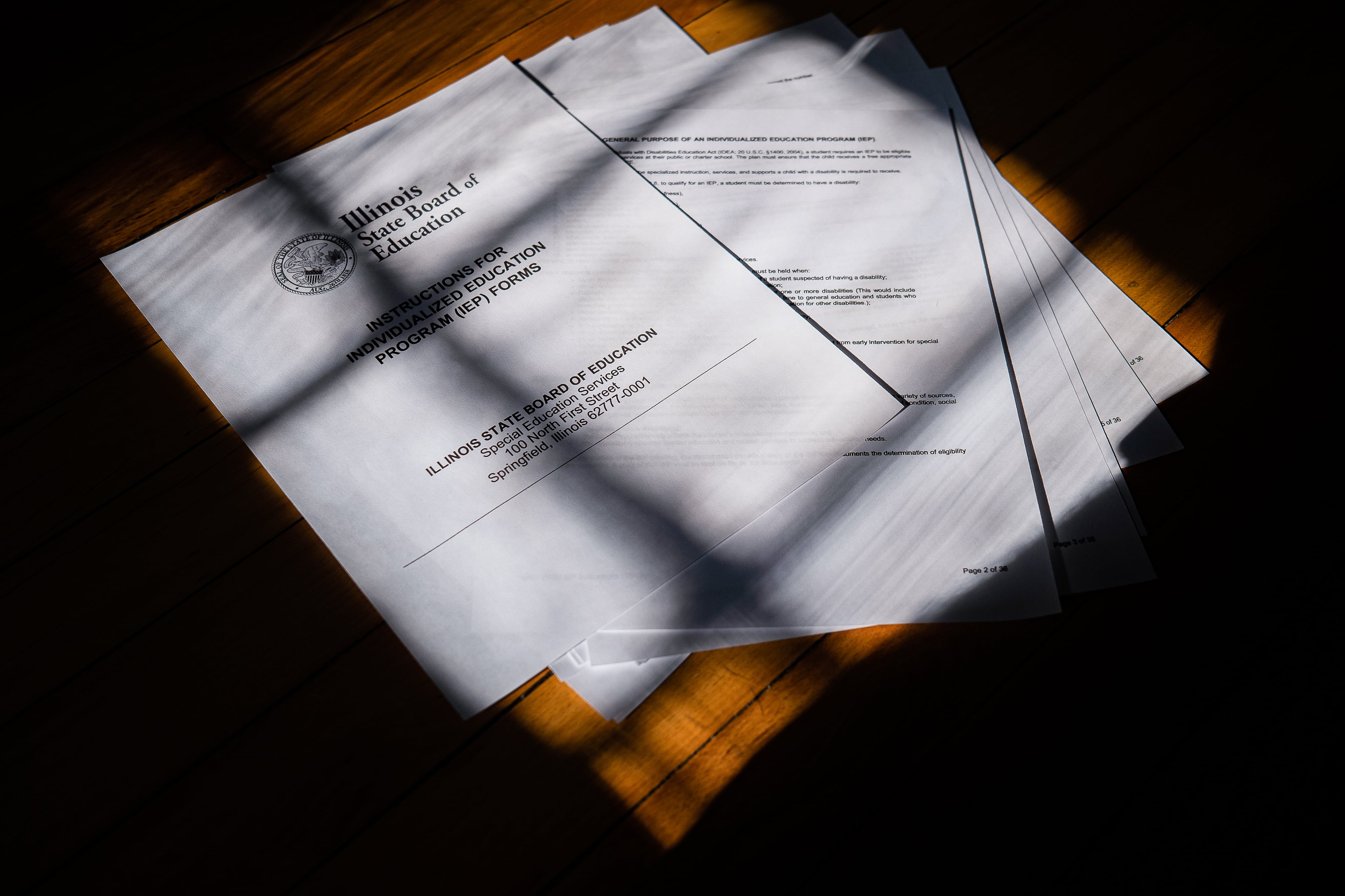

Thousands of Chicago families have been waiting for Chicago Public Schools to create new Individualized Education Programs (IEP) — a legally binding document that outlines services for students with disabilities — or update old ones for students since the pandemic started. Many are still waiting this year.

Chalkbeat Chicago and City Bureau hosted a public conversation in October about IEPs and why they are vital to ensuring that students with disabilities are academically successful. Panelists Chris Yun, formerly of Access Living; Barb Cohen, Legal Council for Health Justice; and Rachel Shapiro, an attorney at Equip for Equality, spoke about how Chicago delayed or denied IEPs in the past up until the current school year.

This year, Cohen said, parents are still being ignored. “Parents are being told that their kids won’t be evaluated,” she said. “I understand a big part of this is that they are overwhelmed with that backlog.”

Here are five takeaways:

During the 2019-2020 school year, CPS failed to complete thousands of IEP evaluations

“Once a year, students and their parents are supposed to have an IEP meeting,” Smylie said. These meetings should identify a student’s disability, as well as what kind of instruction or related services (think: speech pathology or physical therapy) they’ll need. State law requires that schools conduct student evaluations before they’re provided with an IEP (students with an existing IEP must be re-evaluated every three years). After filing a FOIA request, Smylie found that during the 2019–2020 school year, CPS failed to complete more than 10,000 evaluations and annual reviews. (Chicago has a little over 330,000 students; about 14 percent have IEPs.) No evaluation? No updated IEP for students.

Students across Chicago’s South, West, and Far East Sides were most likely to have IEP delays

Smylie said the data they obtained as part of their FOIA request showed CPS students in Networks 11 and 13 were unlikely to receive re-evaluations during the school year. These networks include Englewood, parts of the Southwest Side, as well as neighborhoods on the city’s far south and far east sides. Shapiro said she heard from CPS parents all over the city who felt that CPS lacked a sense of urgency when it came to addressing its IEP backlog.

Shapiro said one of the students she represented went without services for five to six months because CPS didn’t conduct their re-evaluation on time. “The reality is no matter how many services we give [them] now, that can’t make up for the fact that, for those five or six months delay, they didn’t get the support they needed,” she said. This lack of support threatened and likely slowed the student’s progress in school.

Parents should prioritize frequent communication with their kid’s teachers

CPS’s struggles to provide IEPs for students with disabilities predates the pandemic. As Yun put it: “Denial of special education services is a product of CPS culture.” As far back as 2015, CPS was found to be in violation of federal standards that require schools to provide IEPs to their students. Cohen, a parent of a former CPS student with disabilities, said it’s hugely important for parents to communicate with their children’s teachers as much as possible.

“Teachers have always appreciated the communication and the troubleshooting we can do together,” Cohen said. “I think [that relationship] leads to better IEPs.”

Get everything in writing, and request documents you can use to show which services you’re owed.

“Whatever you do, get it in writing,” Cohen said. “If you just [verbally] say to a teacher or case manager that I think I’d like to have my child evaluated...officially, it never took place.” Emails are best because they have the date on them.

Hazel Adams-Shango, an attendee at the Public Newsroom who advocates for students with disabilities in New York City, said that right now is the time to request a copy of attendance and service logs, which you’ll need whenever you request makeup services from CPS.

Word choice matters; consult free legal services before you file any complaints

You don’t need a lawyer to file a state complaint, but it helps to have someone who knows special education law look over your complaint before you send it in. That’s because slight wording changes can make a big impact. “The law doesn’t require a school to do what’s best for your child,” Shapiro said. If you tell officials that a one-on-one aide for your child is what’s best for them, they have no legal obligation to make it happen. Instead, Shapiro says, tell educators and officials that your child “needs” a one-on-one aide or other service.

Equip for Equality provides free services for folks at (866) 543-7046.

If you’re interested in advocating for yourself, your student, or want to help make a difference in your local CPS network, here are a few places to start:

Stay in touch with our guests:

- Rachel Shapiro: (312) 895-7308, rachel@equipforequality.org

- Barb Cohen: (312) 605-1948, bcohen@legalcouncil.org

- Access Living education advocacy team: (312) 640-2100, advocacy@accessliving.org

More coverage on the issue:

- “What more than 50 special education parents in Chicago told us about schooling this fall,” from Chalkbeat

- Read about outstanding CPS transportation requests, of which students with disabilities account for more than 50%, from Chalkbeat

- Read this report on how CPS fell behind on IEP plans, from Chalkbeat