By 8:20 Tuesday morning, the mask-wearing students sitting in classrooms in the state’s largest district will have gotten their temperatures checked, answered questions about COVID symptoms, and taken seats at least 6 feet away from each other — while most of their classmates get ready to learn from their homes.

By all measures, it will be the most unsettling beginning to the school year for the Detroit Public Schools Community District and the three dozen or so other districts and charters in the region that officially launch the 2020-21 school year.

In the lead-up to the first day, debate has swirled about whether students should learn online or in person, about the effect COVID will have, and about how schools will help students who have experienced learning loss or trauma.

Here’s a roundup of what you need to know.

Cue the chaos?

Let’s face it, there are a lot of unknowns as we head into this new school year. But we do know this: Things will go wrong. Technology will fail. Some students will thrive online. Others won’t. Some schools will have positive cases of COVID. The debate about in-person versus online will continue to rage on, particularly since a new state law requires districts to revisit their decisions every month.

Fall learning should be different

Most students in the Detroit district will be learning online. So will many others across the region. How will virtual learning differ from last spring’s experience? For one, expect less flexibility on attendance and turning in assignments this time around. Also, we know many districts provided training for teachers on online instruction, so they should be better prepared than they were in the spring. But many will be teaching live lessons for the first time.

Learning at school, but remotely

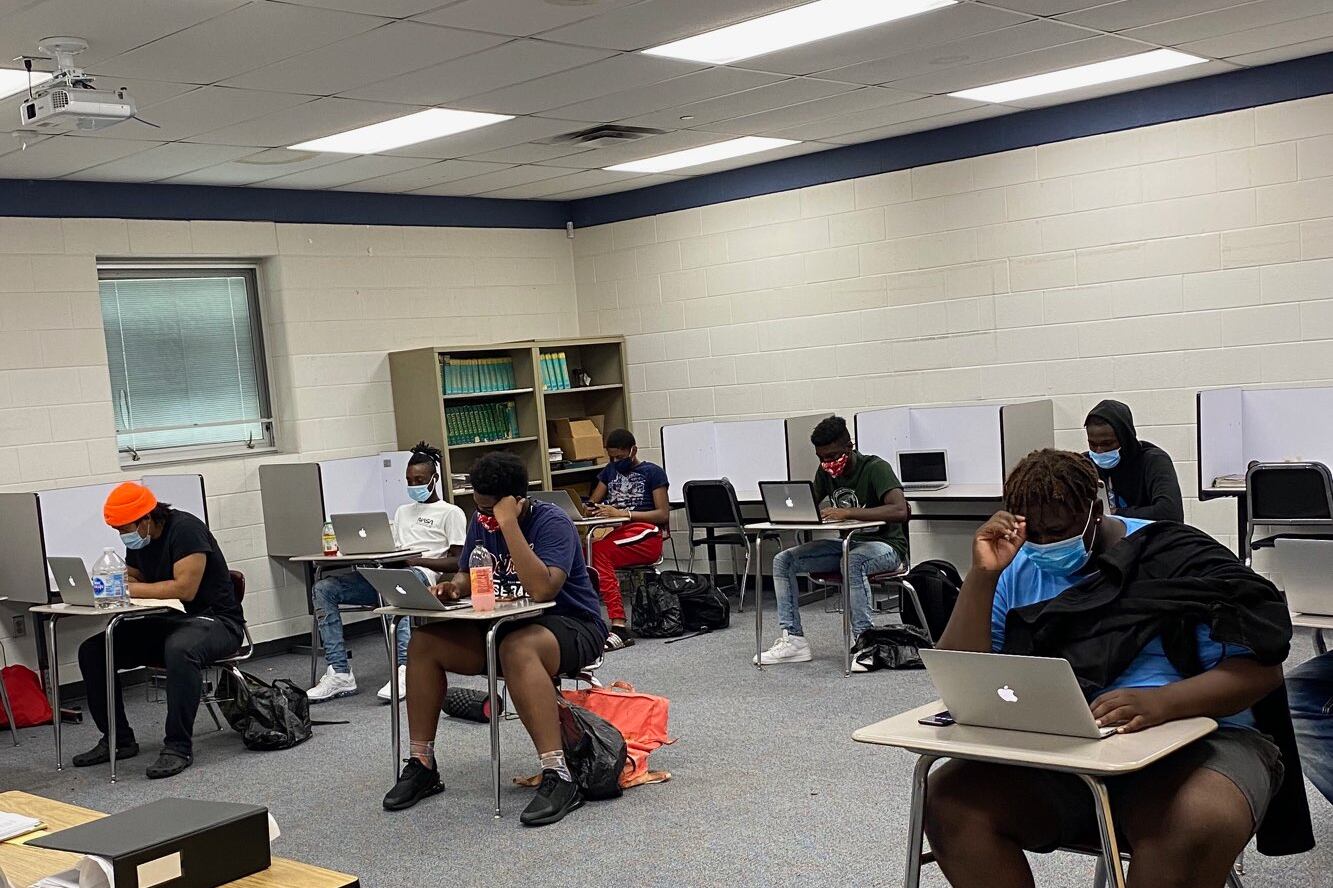

In the Detroit district, students who opted for online learning can sign up to attend learning centers in school buildings, where they can complete their remote work under adult supervision, although not physically with their teacher.

Superintendent Nikolai Vitti said such a program fulfills multiple needs. For one, working parents won’t be home to supervise their children. Others don’t feel comfortable overseeing their studies.

“Public institutions have to put our arms around our most vulnerable families,” Vitti said. “Our families need us more than ever.”

The program is free. In contrast, some districts have received backlash for charging parents for child care programs that allow their children to learn remotely but inside school buildings. Vitti was also critical, saying “It’s a shame,” that districts would charge for such services.

Link between in-person learning and partisan politics

By now, you know what your school’s reopening plan includes. But researchers could have predicted whether a school would open fully in person or fully online based on how your county voted in the 2016 election.

Michigan State University researchers Sarah Reckhow and Matt Grossmann looked at an analysis of reopening plans, which found 59% of Michigan districts are providing at least the option of fully in-person education, while 12% are fully remote. When comparing that data with the results of the 2016 election, this is what they found:

“In heavily Democratic voting counties, school districts are over four times as likely to open fully remote this fall. In heavily Republican counties, school districts are 1.7 times as likely to offer in-person instruction. School districts in political battleground counties are in the middle.”

Why the pattern? The researchers said districts may be following public opinion on reopening, “which is increasingly following partisanship.”

Positive COVID cases

If you’ve been paying attention to what’s happening across the country, you know there’s a good chance schools operating in person will see positive COVID cases. So what happens if that occurs? In many cases, parents won’t even find out. State guidelines give local districts a lot of flexibility in how to deal with positive cases and in notifying people about them.

The bottom line is that unless your child has had close contact with someone who tested positive, you likely won’t find out, at least from school authorities. If a student or employee in a class tests positive, the school will require only those in that class to quarantine and learn online, in many cases. The district would probably only close a building if an infected person had contact with many people throughout it. Want to know how your district is handling COVID? Check their reopening plan that should be prominently displayed on the home page of their website.

Meanwhile, the state has released numbers of outbreaks in K-12 facilities — but not their specific location or name. The state’s website defines an outbreak as “two or more cases with a link by place and time indicating a shared exposure outside of a household.”

Last week, the state’s outbreak tracker listed five new outbreaks and three ongoing outbreaks in K-12 schools. The lack of specifics about where the outbreaks are will change soon. After facing heavy criticism, the state says it will release details Sept. 14 on the locations of the K-12 school COVID outbreaks.

School budget uncertainties

School districts are starting the school year without knowing how much state aid they will — or won’t — receive. The Michigan Legislature has yet to approve a budget, and the pandemic-related recession has led to a steep decline in state revenue. Districts are bracing for a reduction in state aid. The most recent revenue forecast for the state provided a less steep decline, but it’s unclear if that will mean no cuts for schools.

Far fewer teacher vacancies in Detroit

Months after Nikolai Vitti became superintendent of the Detroit district in 2017, the school year opened with more than 300 teacher vacancies. This year, Vitti is expecting vacancies to dwindle substantially, particularly for general education teachers. Districts statewide still struggle to hire enough special education teachers. Last week, Vitti said the district was fully staffed for elementary general education teaching jobs.

Vitti attributes the drop in vacancies in part to two steps the district has undertaken in the last two years: Boosting the starting salary for beginning teachers to $51,000, and giving incoming teachers far more credit on the pay scale for their years of teaching than it had done previously.