Sign up for Chalkbeat Detroit’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system and Michigan education policy.

When Tyra Smith-Bell took the helm of Pulaski Elementary-Middle School, more than three-quarters of the students were chronically absent.

So Smith-Bell set out to transform the school culture and get teachers, parents, and students invested in attendance: She created a spreadsheet for teachers to log absences and late arrivals, required them to call parents the same day a child missed school, and began checking attendance data every day.

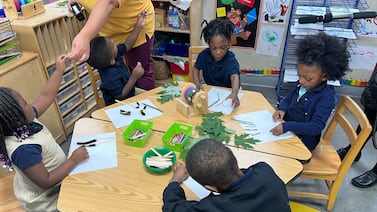

She also looked for ways to address barriers keeping kids from coming to school — offering rideshares to those without transportation, stocking clean uniforms, and creating “Panther Bucks” incentives to get students motivated.

The efforts seem to have paid off.

Over the last six years, Pulaski’s chronic absenteeism rate has dropped by 47.5 percentage points — making it the school with the biggest decrease in chronic absenteeism from 2018-19 to last year in the state, according to a Chalkbeat analysis of data released Wednesday by the state Center for Educational Performance and Information. The analysis looked at traditional public schools.

Other Detroit schools have also made major strides in combatting chronic absenteeism, the Chalkbeat analysis found. Among all of Michigan’s traditional public schools, 14 of the top 15 with the biggest drops over that time period were in the Detroit Public Schools Community District.

The findings of Chalkbeat’s analysis suggest that even compared to other districts serving communities facing systemic barriers that contribute to kids missing too much school, the Detroit district’s efforts are proving to be more effective.

In Michigan, students are considered to be chronically absent if they miss 10% or more of the school year, or about 18 days of instruction in a typical 180-day school year.

Missing too many days of school hinders students’ ability to learn. In Detroit, where chronic absenteeism has long been a problem due to high poverty rates and other systemic inequities, the district has focused on the issue for years in order to improve academic achievement.

Among the schools that reduced absenteeism the most in the state last year compared to pre-pandemic years, nearly all showed improvement in average proficiency on state standardized test results in English and math in the same time period.

As a whole, the Chalkbeat analysis showed, students in the Detroit district were chronically absent at a lower rate than before the pandemic for the first time last year. The district also decreased the rate by nearly 16 percentage points compared to the 2021-22 school year, when quarantine restrictions caused many to miss school.

Superintendent Nikolai Vitti, told Chalkbeat this week the district’s improvement over the years can be attributed to concentrating attendance agents in neighborhood schools with the most absenteeism, changing the mindset of school leaders, hiring more academic interventionists, and adding physical and mental health support for students and families, among other measures.

“Our improvement is rooted in our intentional efforts to expand services to students and families, changing staff mindsets about owning the student attendance improvement process, and increasing family accountability regarding their children’s attendance,” said Vitti.

Creating a culture of prioritizing attendance at Pulaski

At Pulaski Elementary-Middle School, on the east side of Detroit, Smith-Bell says she wanted everyone to have a stake in bringing attendance rates up.

“I asked what can we do to make attendance important to every stakeholder,” she said. “Attendance is not only on the shoulders of our attendance agent – it’s everyone’s business.”

Under her leadership, the 296-student school created a multi-level system to track absences. It includes a schoolwide spreadsheet where absences and late arrivals are recorded and asking teachers to log their calls to parents. Those call logs are then reviewed by the principal.

By 10 a.m. every day, Smith-Bell checks the attendance data. She sees which students are out and asks them where they were once they return to school.

The teachers’ calls to parents also help build a rapport with families and are an avenue to address any needs at home, such as transportation, Smith-Bell said. More than 95% of the students are from low-income homes.

“I have picked up scholars and taken them home to support families myself,” said Smith-Bell. The school also gives bus tickets and rideshares to students in some cases.

After teachers heard from many families struggling to provide clean uniforms for their children, the school began keeping uniforms in the principal’s office. The school also added another washer and dryer to clean uniforms for kids as needed.

A school-based health hub, one of 12 the district started launching in 2023, helps address health barriers for students, said Smith-Bell, as have immunization clinics on campus. Families also have access to food, toiletries, clothing, and other resources at the hubs.

A school-based representative from the Department of Health and Human Services helps make accessing benefits, such as the state’s nutrition program, easier for parents.

The principal said she also makes sure students, staff, and parents know how close they are to reaching the daily goal of 90% attendance.

In the morning announcements, Smith-Bell includes a Powerpoint showing daily attendance data. She also gives weekly attendance updates in the communication sent home to families.

Efforts to improve school climate and culture, electives, and student incentives have also paid off, the principal said.

Every month, the Pulaski’s classrooms compete to get the best attendance and are rewarded with pizza, popcorn, or other celebrations. Kids also work to earn “Panther Bucks” by exhibiting good attendance and behavior to get entry to the “Pulaski Panther Country Club,” where they can play video games and air hockey.

COVID stifled some of the progress the school started to make as in-person instruction was upended. When students came back for in-person instruction in 2021-22, more than 80% of students at the school were chronically absent primarily due to quarantine rules.

But various factors helped the school drop the chronic absenteeism rate down to 45% in 2022-23.

The school had moved to a new building during COVID closures, and Smith-Bell said the upgrade helped make the environment more accessible and comfortable.

“For example, this campus is air conditioned,” said Smith-Bell. “We don’t have to open windows and fight bees.”

Last year, the school’s rate of chronic absenteeism last year was 29.2% — only a couple of percentage points higher than the state average.

Detroit’s districtwide efforts to get kids to school

The Detroit district as a whole has also used a long-term, holistic approach to tackle chronic absenteeism.

That helps it stand out among other high-absenteeism districts, said Jeremy Singer, assistant professor of educational leadership and policy at the University of Michigan-Flint.

Involvement of school leaders and home visits by attendance agents also make DPSCD stand out from other districts, Singer said preliminary research by Wayne State University’s Detroit Partnership for Education Equity and Research, or Detroit PEER, suggests.

The district, where nearly 85% of students are from economically disadvantaged families, has worked for many years to bring the absenteeism rate down.

For example, the district hired more counselors and social workers in recent years to address student’s mental health needs. Schools conduct student surveys to determine the kinds of challenges students are facing and what would make them feel more supported.

“Although we recognize that the concentration of poverty in the city directly contributes to higher rates of absenteeism, we still believe that we can problem solve through operating systems, own the improvement of climate and culture and the student experience, while also thinking more innovatively,” said Vitti.

Offering more electives, fully staffing schools with certified teachers, and hiring more academic interventionists, have given students more reason to go to school, he added.

Last school year, the district began giving high school students financial incentives for perfect attendance.

School leaders have become more invested as the district now evaluates their performance in part on attendance and chronic absenteeism rates, said Vitti.

The district’s chronic absenteeism rate was 60.9% last school year — compared to 62% before the pandemic

Despite the progress, Detroit’s chronic absenteeism rate remains substantially higher than the statewide average of 28% – much of that due to the major social and economic barriers for children in the city and others like it, said Singer.

“We know schools can make progress,” said Singer, “but they alone cannot solve the issue.”

Hannah Dellinger covers Detroit schools for Chalkbeat Detroit. You can reach her at hdellinger@chalkbeat.org.