With one day’s notice, Merry Miller Moon found out on Facebook last week that her son’s school was switching back to remote learning for the rest of the month.

A surge of COVID-19 cases had tipped Clay County from orange to red on Indiana’s color-coded map, triggering health officials to shut down in-person school.

The new Chromebooks that the district had promised this fall hadn’t yet arrived, so the school sent her fourth-grade son home with an older laptop. Miller Moon and her husband rearranged their work schedules. And the family of three in western Indiana settled into the now-familiar but isolating routine of learning from home — and the uncertainty of when it will end.

“I’ve kind of felt like that since March,” Miller Moon said. “Every day it’s like, OK, what’s going to happen today?”

Amid spiking COVID-19 cases, school closures are rippling unevenly across Indiana. While some remain open for full-time in-person instruction, others have shuttered due to high community spread or having too many teachers quarantined.

Schools have reported more than 8,200 cases of COVID-19 among students, teachers, and staff since the start of the school year. So for some, the fall has already been dotted with closures of single classrooms or schools amid widespread exposure, two-week stretches where hundreds have stayed home.

Miller Moon’s district hopes to return in person Nov. 30. Indianapolis schools won’t be back until January at the earliest. In Merrillville, schools haven’t reopened classrooms yet this year.

With the patchwork of local decisions, it’s nearly impossible to say at any given moment how many of Indiana’s roughly 2,300 schools remain open or have moved online. But the Indiana Department of Education is asking schools to track daily attendance based on whether students are in person or online, and report at the end of the year which days were spent on remote learning.

By the end of the year, the state should be able to tell how many days each student spent online or in person, and could use that information to examine trends.

Schools have tried to position themselves to more smoothly transition to e-learning this time around, but changes can still mark disruptions — and disappointment.

In Indianapolis Public Schools, parent Lindsay de las Alas panicked when she found out her children would be learning from home again after just a few weeks back in classrooms.

Her 8-year-old son, Harvey, had been excited to wake up to finally go to school. A second grader at IPS’ Center for Inquiry School 2, he is still learning how to read and needs the direct help from his teacher.

Without that in-person support last spring and at the start of this year, Harvey had struggled with virtual learning, and his parents struggled to give him the help and supervision he needed.

“I’m honestly worried that he’s going to eventually enter third grade with a first-grade reading level,” de las Alas said.

Her 11-year-old daughter, Beatrice, had already started remote learning, sent home to quarantine after being exposed to someone at school who tested positive for COVID-19.

Beatrice has trouble concentrating with her siblings around, trying to do homework in the bedroom she shares with her brother. At times, the online platform doesn’t work, or she can’t figure out how to submit her work online.

“It’s hard for kids that are more social because kids rely on their friends for advice and help,” Beatrice said. “I don’t think virtual learning is working all that well.”

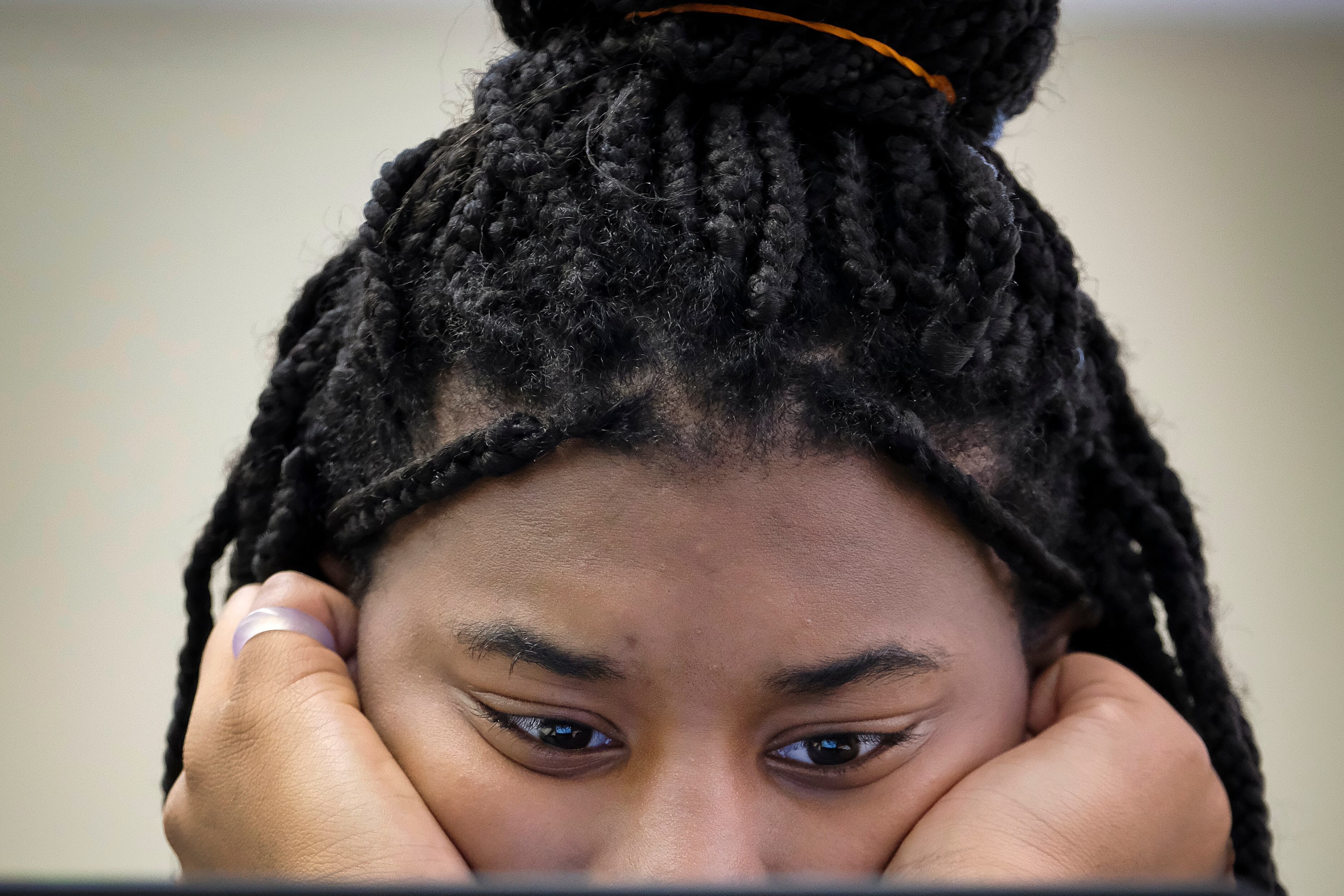

In Crown Point schools, elementary school counselor Andre’anna Maynor has moved all her sessions with students online for at least two weeks. Alongside a positive behavior coach, she works with more than 500 students and worries about losing her connection with some of them.

When in person, Maynor gathered small lunch groups to connect with students who need extra support. Now, she plans to hold Zoom lunches instead. She hopes it’s a way for students to stay excited and engaged online.

The pandemic, she said, “is not going anywhere as of right now. So how can we make things work in the middle of this?”