Yajayra Guzman’s day began with tears.

Her son got upset when they had trouble logging on for his first day of online preschool. Her daughter, a first-grader who remembers in-person school, didn’t like the virtual substitute.

“She was just crying, saying that this was boring, that this is not what school is like — that she doesn’t get it, and she doesn’t know what are they talking about,” Guzman said.

Then, Guzman herself started to fall apart. She loved her children’s school but keeping them enrolled and engaged felt increasingly untenable.

Indianapolis Public Schools, which has more than 25,000 students in district-run schools, began the year entirely online today, joining a national experiment in remote instruction amid the coronovirus pandemic. It will test whether the school experience can be replicated online, whether students will learn as much with remote instruction as they would’ve in classrooms, and whether online school can be more than a stopgap measure.

And the results will be measured household by household, day by day.

For Guzman, even high-quality online instruction won’t solve her essential problem: She and her husband both work full time, and most days her children will be with her mother, who does not speak English and won’t be able to help them navigate virtual school.

“I would not mind if they were a little bit older. ... They would know how to read. They would know their numbers,” said Guzman, who took time off work to help her children with the start of school. But without her there to supervise, she said, “they’re going to be left behind.”

Now, Guzman is considering withdrawing her children from IPS and enrolling them in Warren Township, which is offering in-person instruction.

Present in the classroom

Although IPS offered a hastily developed version of remote instruction when schools closed due to the coronavirus in March, officials say this time will be different. All students will get district-provided Chromebooks and iPads. Students will be expected to follow a daily schedule. And teachers will spend more time leading their classes through live video.

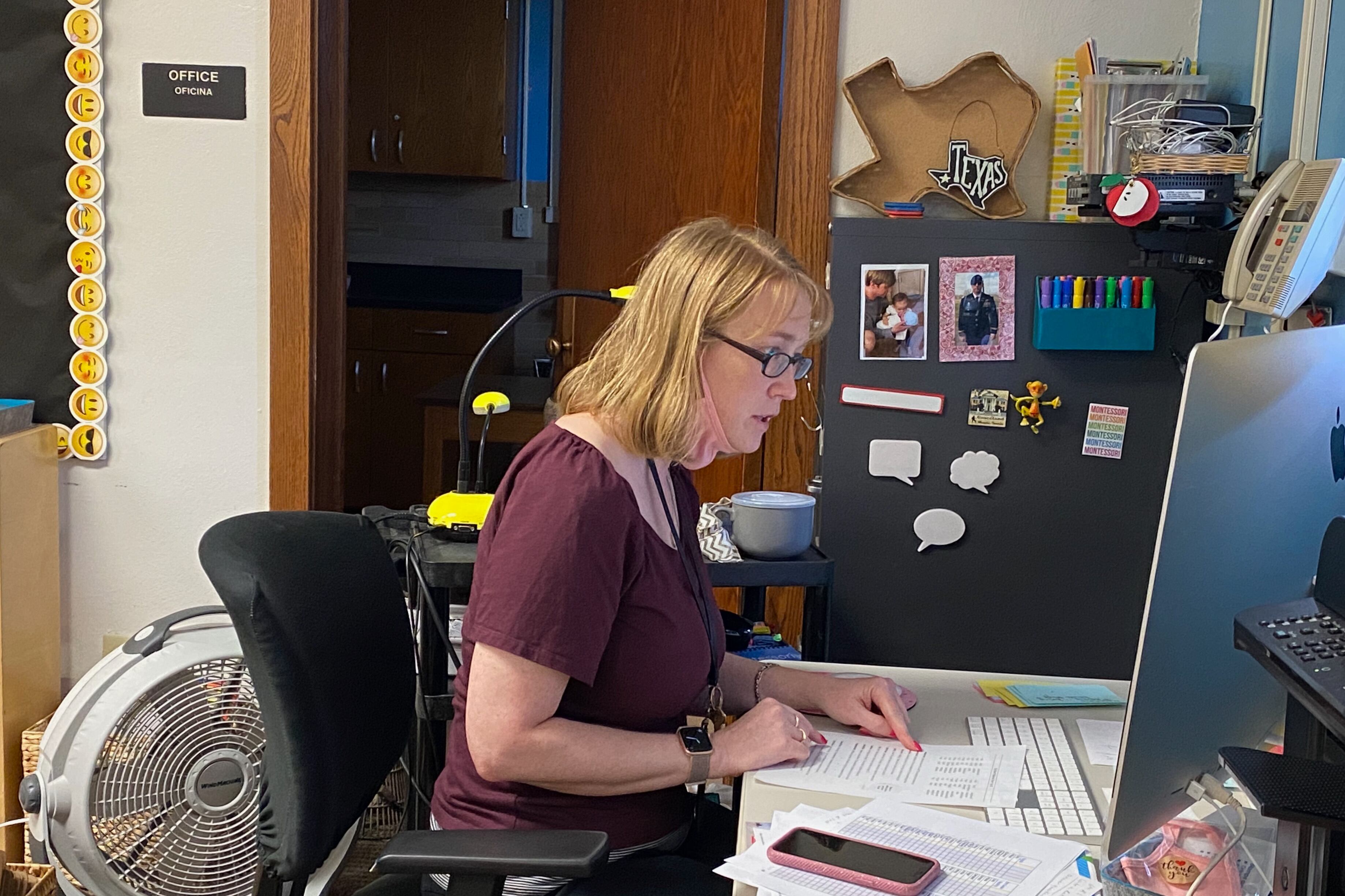

For Juli Cooper, who teaches sixth and seventh grade at School 87 northwest of downtown, the morning began with setting expectations. Rather than teach from home, she chose to go to her classroom so students could see her present at the school building. She wanted them to know she took remote school seriously, and that they should, too.

As she worked with a small group on vocabulary, Cooper looked at a grid of student faces on her monitor. She checked in with them one by one to be sure they knew the next steps to make flashcards. She guided them through the process of logging on for art, their next lesson. When she gave them the choice to stay on the video call or log off while they worked, faces began slowly disappearing until the screen was empty.

The first morning went unexpectedly smoothly, Cooper said, with all but one of her 28 students logging on. Cooper spent hours preparing for the year, figuring out how to transform lessons for the internet. She tried to think of everything students would’ve had in the classroom, even sending home bags of rubber bands for their index cards. “It’s like your first year teaching again,” said Cooper, who has taught for 19 years.

‘The easiest day’

There have been some bumps in the road for IPS. On Sunday before school started, IPS announced that a technical glitch could sometimes prevent teachers and classmates from seeing video of students, although audio should work for everyone. The district is updating accounts to fix the issue and expects it to be resolved by Tuesday morning, the statement said.

Some families struggled with technical problems, child care, and other barriers on the first day of school. Others seemed happy to send their children back to virtual classes, posting cheerful photos on social media of them studying at desks.

Whether students, especially young children, have a good experience with remote instruction will likely hinge on whether their parents are able to supervise closely or get help from others.

Hannah Northup, who has a daughter in kindergarten and a son in third grade, said that the first day went really well — especially compared with the chaos of the spring. She and her husband both work, and managing remote learning last school year was overwhelming. So this fall, they are using money in a child care flexible spending account to pay someone to help.

The woman they hired has experience in education and spent the day supervising the children when they learned online. “I know we are very fortunate. Not all parents are getting to do this,” Northup said. “It’s been the easiest day for me as far as e-learning goes.”

For Brittany Hernandez, whose son is in preschool, the morning also began relatively smoothly. He joined his class online to meet his preschool teacher. With Hernandez by his side, he did school work on his tablet, and while he was often distracted, he was also excited by some of the work.

Hernandez left her job as an insurance agent earlier this year, but she hopes to go back to work soon. She’s unsure how she will handle child care once she does. “If we continue doing virtual,” she said, “I really don’t know how it’s gonna be for us once I start working.”