Judith Hernandez never thought she’d miss the old remote learning.

When the pandemic confined her four children to their home this spring, their schools in Newark, N.J. distributed paper packets, loaned out laptops, and posted online assignments. Hernandez helped her children complete their work, while their teachers recorded short videos and checked in by phone or text. It wasn’t much, but it was manageable.

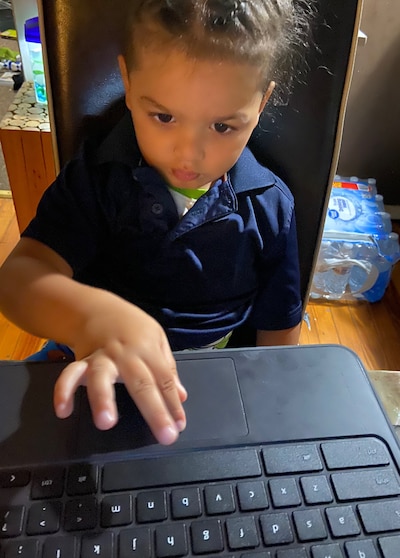

Six months later, as the new school year starts with classrooms still closed, Hernandez’s children in grades 2-4 spend most of the school day in live video classes. Hernandez, who also has a newborn, scurries between her children, troubleshooting tech problems and urging them to stay focused.

Suddenly, it seems, remote learning has gone from on-your-own to always-on — and some families aren’t pleased.

“It’s supposed to be like normal class but it’s just not the same,” Hernandez said last week as classes started. “This whole computer thing is insane.”

With the coronavirus still untamed, an estimated 85% of school districts nationwide are continuing to offer some remote learning this fall. But, this go-round, many districts are ratcheting up their demands.

Now, some students are expected to attend online classes that approximate a traditional school day, with consecutive periods of live video lessons interspersed with brief “brain breaks.” In Newark, elementary and middle schools must provide 290 to 350 minutes of remote learning each day, according to district guidelines.

Districts made the shift partly out of necessity, having watched many students fall behind during the looser remote learning, and partly due to capacity, with more families now equipped with the devices and Wi-Fi needed for online classes. Districts also faced external pressure. States are now requiring more live remote instruction and families demanded it after some children struggled to complete assignments this spring with little teacher guidance.

But now resistance is beginning to bubble up against the more intensive remote learning, with some families and educators saying districts lurched from too little online instruction last spring to too much this fall. Meanwhile, a handful of districts are limiting live virtual classes due to concerns about screen time and a recognition that some students have jobs and babysitting duties during the day.

For districts trying to strike a balance between structure and flexibility during remote learning, the big question now is: What’s the right amount of live instruction?

“I think there will be a natural trend to see that requiring kids to sit in live Zoom meetings for hours at a time is not sustainable,” said Kerry Rice, a professor of educational technology at Boise State University. “They have to come up with other solutions.”

The shift to ‘synchronous’

In the spring, remote learning was more emergency homeschool than online academy.

Because many families lacked reliable Wi-Fi or laptops, most districts were reluctant to mandate live online lessons. Instead, teachers assigned work and checked in with students, while parents did their best to assist their children.

“I had to sit down with him and show him things I didn’t know,” said Vianna Jaramillo, whose son is in the fourth grade at Newark’s Oliver Street School. “I’m Googling everything and YouTubing videos like, ‘What the hell is this?’”

Newark is taking a very different approach this fall. For instance, middle schools must now provide 100 minutes of remote learning per day in reading and writing, 100 minutes in math, and 60 minutes each in social studies and science, along with 30 minutes of tutoring, according to the district guidelines.

Students can spend some of that time working on their own. But a significant chunk must be devoted to “synchronous” learning: live online classes that can include teacher lessons, class discussions, and small-group sessions. The upshot is that Newark Public Schools students now spend most of the school day in front of their computers, often logged onto the videoconferencing tool Webex.

This fall, “there’s more of a demand for the in-person feel of Webex sessions and live teaching,” said Christopher Canik, a math teacher at Newark Vocational High School where students attend four 80-minute classes per day. “Any time I’m teaching actively, that means I’m going to be on Webex for the entire 80-minute period.”

Districts across the country have made a similar shift. Many are pivoting to a more structured version of remote learning this fall that builds in more time for live online classes, said Alice Opalka, a research analyst at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, which is tracking school reopening plans.

One reason is demand from families for more teacher-led instruction, Opalka said. Another is states reinstating class-time requirements that they suspended this spring. For instance, New Jersey recently issued guidance requiring four hours per day of “active instruction” by teachers, whether students are learning remotely or in person.

In the spring, just one-third of districts required teachers to interact with students remotely, according to a Center on Reinventing Public Education analysis of a nationally representative sample of 477 districts. This fall, 87% of districts are requiring at least some live online instruction, according to the center’s review of more than 100 districts’ reopening plans. (That sample includes the nation’s largest districts but is not nationally representative.)

“Most of the districts we tracked in the spring were not requiring synchronous instruction,” Opalka said. “At this point, the majority of the ones we’re tracking in our bigger-city database are.”

A brewing backlash

After pleading for more live lessons this spring, some families now say schools have overcorrected.

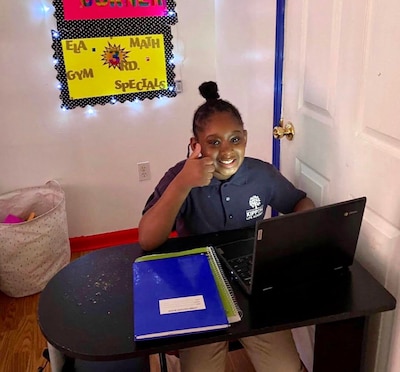

Shanefah Allen said her three children in Newark schools spend most of their day on Webex since classes started Sept. 8. Their teachers are constantly asking students to turn on their cameras, mute their microphones, and pay attention, Allen said. But that’s not easy for many students, including Allen’s fourth-grader who has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

“They can’t just keep sitting in front of a computer all day like they’re at an eight-hour job,” said Allen, who had to switch to the evening shift at her own job at a ShopRite supermarket to supervise her children’s online learning. “They’re getting antsy — they’re kids.”

The pushback to more regimented remote learning is flaring up across the country.

In Chicago, teachers union leaders say the district is trying to squeeze too much online learning into the school day, which they argue is not developmentally appropriate for young students. In Broward County in southeastern Florida, district officials promised to reduce the amount of live instruction in the lower grades after some parents complained about excessive screen time. And in the Memphis region, more than 23,000 people have signed an online petition calling for the Shelby County school district to shorten the virtual school day by three hours.

“You can’t expect kids to sit in front of a computer from 8-3 everyday!” one person wrote on the petition. “That’s ridiculous!!”

Getting the balance right

School districts are in a tough spot.

They don’t want to exhaust students or turn them off from remote learning. But they’re also loath to ease expectations, which could exacerbate the learning loss many students suffered this spring.

District officials in Chicago and Shelby County note that their remote learning plans weave in breaks, physical activity, and off-screen work time along with live lessons. In Newark, the district guidelines advise teachers to limit their live lessons to 30 minutes per subject in elementary school and 40 minutes in high school. They also ask educators to offer “asynchronous” instruction, such as recorded lessons that students can watch if they miss a live class.

“The reality is that instruction is being very much tailored to the individual needs of students,” said Superintendent Roger León.

Some charter schools have also ramped up real-time remote learning this fall.

KIPP New Jersey, which operates schools in Newark and Camden, experimented with some Zoom classes this spring but mostly relied on recorded lessons and online assignments. Now, students are attending Zoom classes for up to three-and-a-half hours a day in elementary and middle school and up to five hours daily in high school, said Executive Director Joanna Belcher.

Teachers are using tools to make their online classes resemble traditional ones, Belcher said. Zoom’s “breakout rooms” allow students to work in small groups, while certain apps let teachers view and comment on students’ classwork in real time — almost as if they were standing over their students’ shoulders.

“In physical school, we talk about making lessons so engaging that kids are on the edge of their seats,” Belcher said. “We’re still trying to create that on Zoom.”

Other charters have gone a different route, using Zoom classes mainly to reinforce material that students learn independently.

Noble, a Chicago-based network of 17 charter high schools and one middle school, reserves about half of its five-hour remote school day for live sessions. But those are optional and mainly focused on relationship-building and class discussions; students are not penalized if they don’t attend. Teachers present most new material asynchronously, through videos and readings that students access on their own time.

“This came down to equity,” said Noble’s Chief Education Officer Kyle Cole, who explained that some students struggle to attend live online classes due to W-iFi issues or because they must look after younger siblings. “Their ability to be on a computer at a given time every day just couldn’t be guaranteed.”

A lot of schools entered the fall hoping to replicate a traditional classroom experience online, Cole added. But the spring taught his network that some students simply can’t attend online classes on a set schedule.

“I’d imagine that’s going to be true for every school across this country,” he said. “If there isn’t flexibility built into their model, I think they’ll probably end up having to react to that and build it in.”