Leer en español.

When Mily Cepeda returned to Newark to teach in 2019, she felt like it was a meaningful homecoming.

“I had been in Florida teaching, but I kept feeling like I had to move back to Newark and pay it forward,” said Cepeda, a Newark native and graduate of East Side High School. “It was my calling.”

Cepeda also saw the need for special education teachers who are bilingual — she speaks Spanish and works with many students in fifth to eighth grades who are navigating both a language barrier and learning with a disability.

She started teaching two decades ago but was in her first year at Louise A. Spencer Elementary School in Newark when the pandemic struck. Like in many communities throughout the U.S., Newark’s Black and Hispanic neighborhoods were especially hard hit. By this June, nearly 360 out of every 100,000 Newark residents had died from COVID — twice the national average.

Cepeda was one of more than 275 educators, parents, and students who wrote into Chalkbeat when, as part of our partnership with Univision called Pandemic 360, we asked our readers in New York City and Newark to tell us how the pandemic impacted their school communities. She spoke with Chalkbeat about her approach to visual teaching in a virtual world, the importance of strong parent relationships, and why every teacher should take mental health first aid.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Why did you decide to return to Newark to teach, and what was your first year back like?

I was born and raised in Newark and in our public schools. I started teaching in 2000 before moving to Florida, where I took a break and was caring for my son. We both have a bleeding condition — hemophilia. I felt I belonged in the classroom and decided to come back. I saw the need for bilingual special education, for teachers who can navigate both the language barrier and learning challenges. It was my calling. I had some dynamic teachers when I went through Newark Public Schools, and I wanted to pay it forward.

Newark Public Schools hired me in the fall of 2019 and was getting everything established. My kids were getting to know me, and I had close communication with my parents both in Spanish and English. Then comes March of 2020. I still remember my son, who is in high school, calling me frantically one day in March to say that his school was telling everyone to go home. Our school made the call not long after.

I took everything out of my classroom, packed up my Jeep, dumped everything on my living room floor, and cleaned it all. Then I took a breath and said, ‘OK, what am I going to do now?’ I instantly started printing off and collecting packets for my students.

How did you adjust to teaching your students in a virtual world?

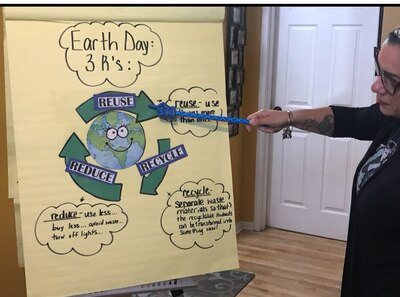

I and other teachers at my school got masked up and gloved up to pass out Chromebooks to our students when all of this started. I also designed and delivered take-home packages for each of my students — literacy packets, pencils, and paper, and other supplies that I knew not all of my kids would have at home. This was a very frustrating time for my kids, many of whom are very visual learners.

I had to get a lot of students and their parents on FaceTime during the transition, trying to tell them why it was crucial that the children signed on to class every day. After live classes, I would spend several hours each day recording videos in Spanish and in English of lessons and telling students how to do their homework step-by-step. I would often videotape just my hands filling out worksheets — again, my students are very visual learners. I would often sit beside them in class and show them what I wanted them to do, then watch as they tried to copy me.

You mentioned that many in your school community have faced hardships during the pandemic — and even before. What have your students experienced and how have you responded to their families?

I know parents who have lost work, who were evicted from their homes. Some students don’t have enough food. And especially at first, it was heartbreaking how many of my kids had problems with technology. It took a lot of advocating to get them set up with Wi-Fi and a lot of coaching to get them comfortable with the Chromebooks.

We’ve all lost people, family and friends, due to COVID. Teachers, too — I know a lot of teachers who had to put on a poker face when they logged onto class every day. You have to be there for your students and families, even when you yourself have lost a loved one. I believe a lot of teachers deserve an Oscar after this year. We’ve all had to act. It was hard to be joyful, but every week I would put on silly hats and do YouTube sing-alongs — whatever I could to get my kids to smile regardless of what they faced.

How do you feel your school community has supported students and educators struggling with the loss of loved ones or financial trials?

Our guidance counseling department meets with students every morning. Teachers have really been community coordinators in many ways. We communicate with families about COVID testing, about food banks, about financial aid programs. There are a lot of resources but how to access them doesn’t always make it into a home.

For our family, this has been a difficult year. My son and I have continued school at home because we have hemophilia. We spent so much of this year so scared and careful. We all — my husband, son, and I — got COVID in January and we were devastated. I was so angry, but we fought it for a week and a half and pulled through. So many, including within my own family and friends, did not survive this pandemic. We as a school family have to acknowledge that and treat one another with such care and compassion as we all try to move forward.

Parent and teacher relationships have been essential to weathering this year in many communities. How has the pandemic affected your relationships, and what have you learned?

I feel like we’re best friends, I know it sounds a little cheesy. I told my parents from the start of the pandemic that we’re all resilient and we’re here in this together, so let’s make it work. I’ve spent a lot of time calling and FaceTiming parents this year. Honestly, I feel like we’ve become much closer. We have to communicate more because their students are adjusting to so much. And they have so many questions.

When I get a random text from a parent, I feel a sense of joy because they were comfortable enough to reach out to me, and now we can have a conversation and start a relationship. If they know and trust me, they can better help me teach their kid. If you asked me the one ingredient to a good relationship, I would say that communication is all you need.

What specific mental health and learning supports do you want to see schools add, given the hardships of this year?

I witnessed a lot of stuff this year: crying voices from parents, children talking about losing their loved ones. I decided this year that I needed to find more opportunities to learn about mental health and wellness. I took a mental health first aid class from the Hemophilia Foundation. I think educators have a role to recognize when a student might be in crisis and help them take that first step, to open a dialogue.

My hope is that schools provide more counseling opportunities for students and more activities that center on mental health, but I also truly want to see all teachers trained on mental health first aid. I know I’ll be sharing my knowledge with coworkers this year.

Is there any element of teaching during a pandemic that you hope continues after life returns to some sense of normalcy?

I’m getting a doctoral degree (I actually graduate in a few weeks!) and have focused my studies on parents of students with chronic illnesses and their resilience. I hope the hybrid model of learning is something districts continue to offer, especially for kids with chronic illnesses who often have to miss in-person classes. I also hope society’s new or renewed focus on mental health is here to stay.