Newark schools have a new history curriculum. It has a long history of its own.

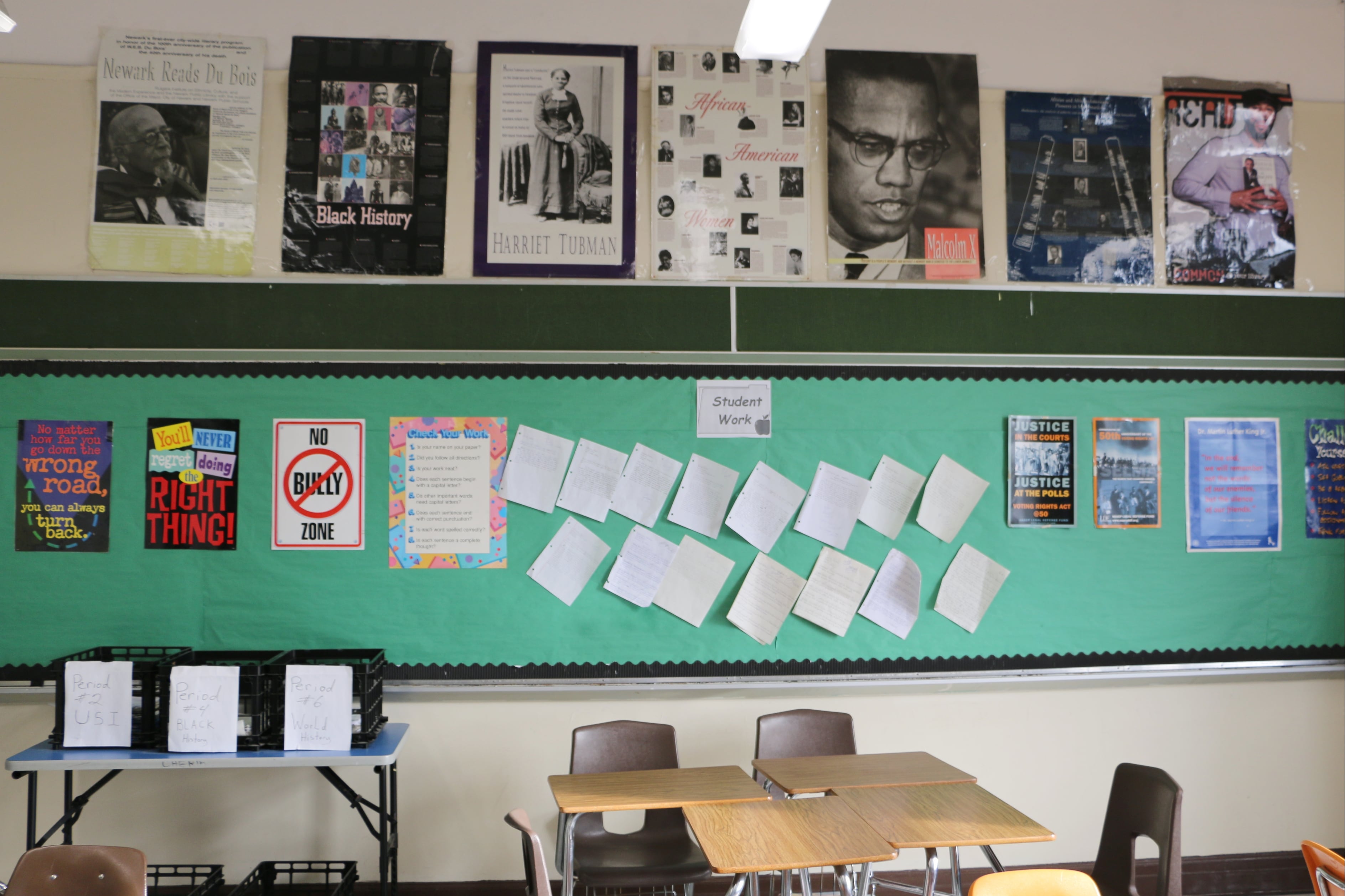

The school district’s new curriculum includes lessons for every grade level about the contributions — and oppression — of Black people and other marginalized groups in America. Students will learn about ancient Africa, the enslavement of African people in the United States, the long struggle for civil rights, and much more.

For decades, Newark community members have called for schools to thoroughly teach African American history; in the late 1960s, some Newark students even staged a school boycott in part to demand that officials add “Negro history” to the curriculum. In 2002, New Jersey adopted the Amistad law, which required schools to teach African American history. But many districts failed to abide by the new rule.

“Amistad is written in the legislation,” Newark Superintendent Roger León said in 2019, “but if you try to find it in any of our curriculum, it is absent.”

León has set out to change that. In 2020, the district rolled out a new curriculum — essentially teaching guides — for grades K-5 that combines social studies and English language arts and puts Black, Hispanic, and indigenous people center stage. And, after teachers wrote then rewrote a new history curriculum for grades 6-11, the district finally introduced it in schools last fall.

Officials say the goal of the new materials is to ensure that students learn accurate accounts of American and world history — not sanitized or Eurocentric versions.

“Those histories marginalized people,” said Carynne Conover, the district’s social studies director, during a recent presentation. “We’re just putting them back in.”

Newark has undertaken this work at a time when some states are trying to restrict what students learn about America’s past. Republican lawmakers in at least 36 states have sought to limit certain classroom discussions about race and racism, which conservatives have dubbed “critical race theory.”

“In this district, we are pioneers,” Newark school board member Asia Norton said in October, during a discussion about the new curriculum. “We didn’t need someone to talk about critical race theory for us to do this work.”

But even as board members tout the curriculum, few parents or community members know what’s in it. The rollout of the new materials, which some teachers say was rushed, was done with little fanfare. The district hasn’t made the documents easily accessible, and did not invite community members to speak during an online “community roundtable” last month about the curriculum.

District officials did not respond to questions for this article.

Nadirah Brown, whose daughter attends Harriet Tubman School, said she had no idea schools had adopted a new history curriculum.

“This is news to me — and I attend all the PTA meetings,” she said. “I can’t tell you what is being taught.”

So what is this curriculum and how is it working out in schools? Chalkbeat’s guide has the answers.

What is the new curriculum?

Curriculum here means a collection of materials that shape what students learn.

Mainly intended for teachers, the materials include weeks-long “units of study,” daily lesson plans, readings, discussion prompts, and learning goals and activities. They cover social studies and English in grades K-5, and U.S. history, world history, and geography in grades 6-11.

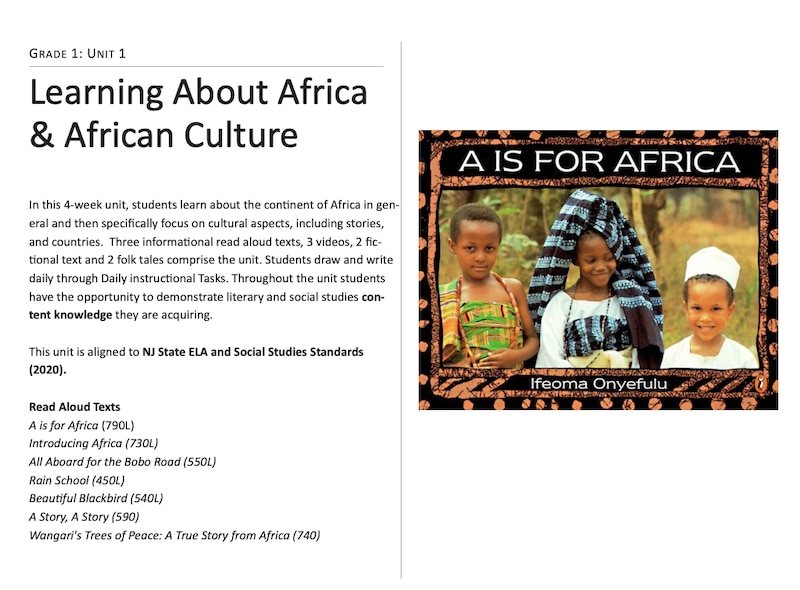

Here are some examples of the lower-grade teaching units..

- Grade 1: “Learning About Africa & African Culture,” a four-week unit about the countries and cultures of Africa.

- Grade 2: “The Science of Skin Color and Colorism,” a three-week unit about the biological processes that produce skin tones and the concept of “colorism,” coined by writer Alice Walker to describe prejudice against people of the same race based on their skin color.

- Grade 4: “Life After 1492: Native American Assimilation, Human Rights, and Genocide,” a five-week unit about the history of Native Americans after Christopher Columbus’ arrival, including natives’ forced assimilation and their ongoing fight to protect their rights and traditions.

- Grade 5: “Initiating Change: Boycotts, Marches, Sit-Ins and Strikes,” a four-week unit about the movements in the U.S. in the 1950s and 60s for African American, Latino, and workers rights, led by Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Chavez, and others.

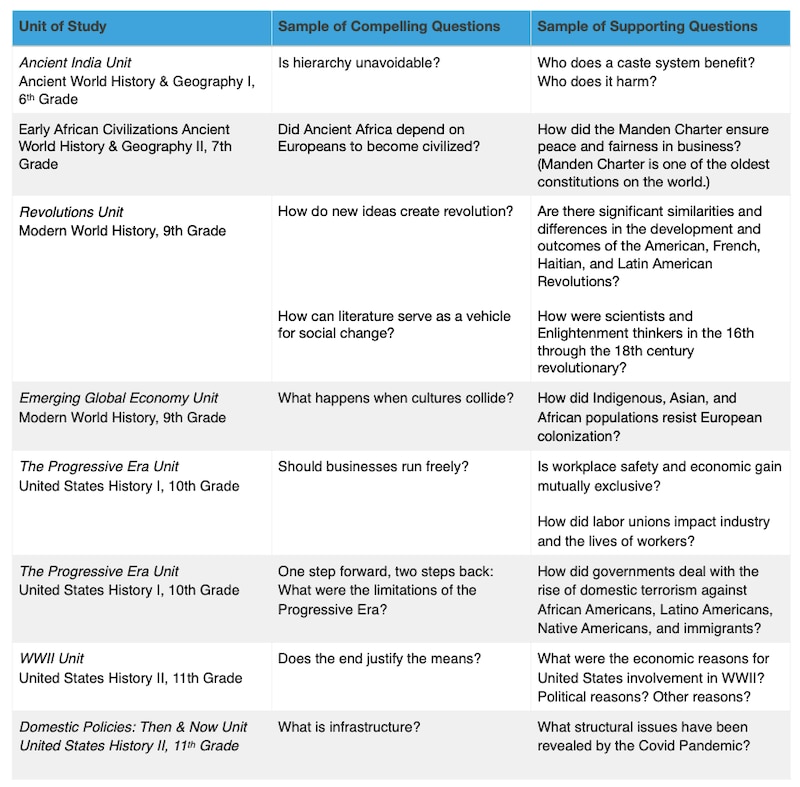

Here are some examples of units from the grades 6-11 materials, which include “compelling questions” to guide student thinking.

- “Early African Civilizations: Did Ancient Africa depend on Europeans to become civilized?”

- “Emerging Global Economy: What happens when cultures collide?”

- “World War II: Does the end justify the means?”

In addition to the district-created materials, the board also approved new social studies textbooks last August. Harcourt Mifflin Houghton, a Boston-based education publisher, will provide the books under a one-year, $1.75 million contract.

Who made it?

Newark educators created most of the new materials.

Thirty district teachers and 16 administrators convened last summer to write the social studies curriculum for grades 6-11, which includes 68 different units, Conover said in her April presentation. The materials are intended to meet the mandate of the Amistad law, as well as other New Jersey laws requiring students to learn about the societal contributions of LGBTQ Americans, people with disabilities, and Asian Americans, Conover added.

The new materials, which teachers started using this school year, are actually the district’s second attempt to create an Amistad-compliant curriculum for the upper grades. A group of educators wrote such a curriculum in 2020, but Conover, who was not involved in that process, decided to try again.

“She felt the curriculum wasn’t as in depth as she had hoped,” said Yvette Jordan, a high school history teacher who helped write the 2020 curriculum for the upper grades but was pleased with the revised version. “I think she and the teachers did a phenomenal job.”

District educators and staffers also wrote the K-5 curriculum.

It intentionally features books written by and about people of color, said Mary Ann Reilly, the district’s assistant superintendent in charge of teaching and learning, during a talk in 2020 hosted by Rutgers University-Newark. When students see their own cultures and ancestors reflected in the curriculum, that captivates their interest and enhances learning, Reilly said.

“This is a major lever for student achievement,” she said, adding that “the community has been asking and wanting us” to more deeply embed African American history in the curriculum.

Where can you find it?

It isn’t easy.

The district website includes a “Curriculum Resources” page, which has a separate curriculum section. However, the social studies materials only include grades 6-12 and appear to be outdated; they don’t feature the newly adopted teaching guides. A separate Amistad section is labeled “Under Construction,” and also does not include the new materials.

The Newark school board uploaded some, but not all, of the materials to its online agenda when the board approved them in 2020 and 2021 — but parents and members of the public must search through two years of agendas to find them.

The lack of curriculum transparency is not limited to Newark — other New Jersey districts also make it difficult or impossible for the public to review the documents that dictate what students learn.

In response to recent controversy about sex education, the state Senate’s education committee advanced a bill on Monday that would require districts to post their health curriculums online. Sen. Vin Gopal, the committee chair, said a forthcoming bill will extend that requirement to other subjects.

What are people saying about it?

The curriculum has received some favorable reviews.

Charles Payne, an African American studies professor at Rutgers University-Newark and an expert on school reform, gave the K-5 materials high marks during the university event in 2020.

“One of the biggest things for improving districts is high-quality curriculum and teaching,” he said. “This curriculum looks high quality to me.”

Other people have expressed concerns. Wilhelmina Holder, a longtime Newark activist who died this month, said the K-5 curriculum materials she reviewed in 2020 were “terrible” and “did not live up to the letter of the [Amistad] law.” She said district officials were receptive to her feedback, but did not show her any subsequent revisions.

In September, the district hired a local historian, Junius Williams, to help develop additional K-5 materials. He told Chalkbeat that the district also asked him to review the teacher-created curriculum.

Other criticism has focused on the district’s rollout of the curriculum. Teachers said the new textbooks did not arrive at schools until late September — after classes had already begun. One high school teacher said the curriculum provides lesson overviews, but teachers still must create their own worksheets and assessments.

Another teacher said the district didn’t give educators enough time to get acquainted with the new curriculum.

“Nobody liked how it was rolled out at the beginning of the year,” said the teacher, who requested anonymity to avoid retaliation. “It shouldn’t have been rushed in — particularly coming off a COVID year of chaos.”

Yet other teachers said the curriculum is worth celebrating, even if it leaves room for improvement.

“Although the Amistad curriculum is not perfect, it has opened up our classrooms to factual and balanced instruction in history,” said Bashir Muhammad Ptah Akinyele, a longtime history and Africana studies teacher at Weequachic High School.

Nadirah Brown’s daughter, Kareenah, said she learns about historical and current events in her seventh grade social studies class through news articles and the new textbook. Kareenah said the class has studied famous figures, such as her school’s namesake, Harriet Tubman, but has not gone as deep into African American history as she would like.

“It feels like I’m just getting retaught what I already know,” she said.

What’s next?

More materials are on the way.

Conover, the social studies director, said her team is working on assessments for the new curriculum, as well as a freestanding social studies curriculum for grades 4-5 — a shift from those created before she arrived that combined social studies and English.

They also have created teaching guides for seven Advanced Placement social studies courses to be offered next school year, and are developing survey courses for high schoolers on African American, Latino, and Caribbean history, Conover said.

Her team also is exploring the creation of high school elective courses focused on topics such as the roots of inequality in the U.S., the politics of conservatism, and the history of Black women in music.

This summer, the educators who wrote the grades 6-11 curriculum will work on improving it.

“Like the U.S. Constitution, curriculum is a living document,” Conover wrote in a district newsletter. “It requires space to change and expand.”

Patrick Wall is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Newark, covering public education in the city and across New Jersey. Contact Patrick at pwall@chalkbeat.org.