The number of education department staffers who have died as a result of the coronavirus reached 74, officials announced Monday.

The deaths represent the growing toll of the virus on the education department’s 150,000 employees and have left school communities grieving for staff members who will not return when schools reopen their doors.

The tally, spanning March 16 through May 8, represents an increase of three deaths since last week, and is based on reports from family members, officials said. (One death reported last week was found to have not been related to the coronavirus.)

As school buildings have been closed since March 23, the number of education department deaths may rise more slowly — through the city is running regional centers for the children of essential workers and food distribution centers staffed by department employees.

Still, the potential dangers of reopening school buildings in September — as the virus is likely to still be active — have sparked concern about how school communities will be protected, particularly staff who are in high-risk groups.

Teachers union officials have suggested that universal testing, temperature checks at school entrances, and possibly even staggered schedules could be prerequisites for sending educators back into their classrooms.

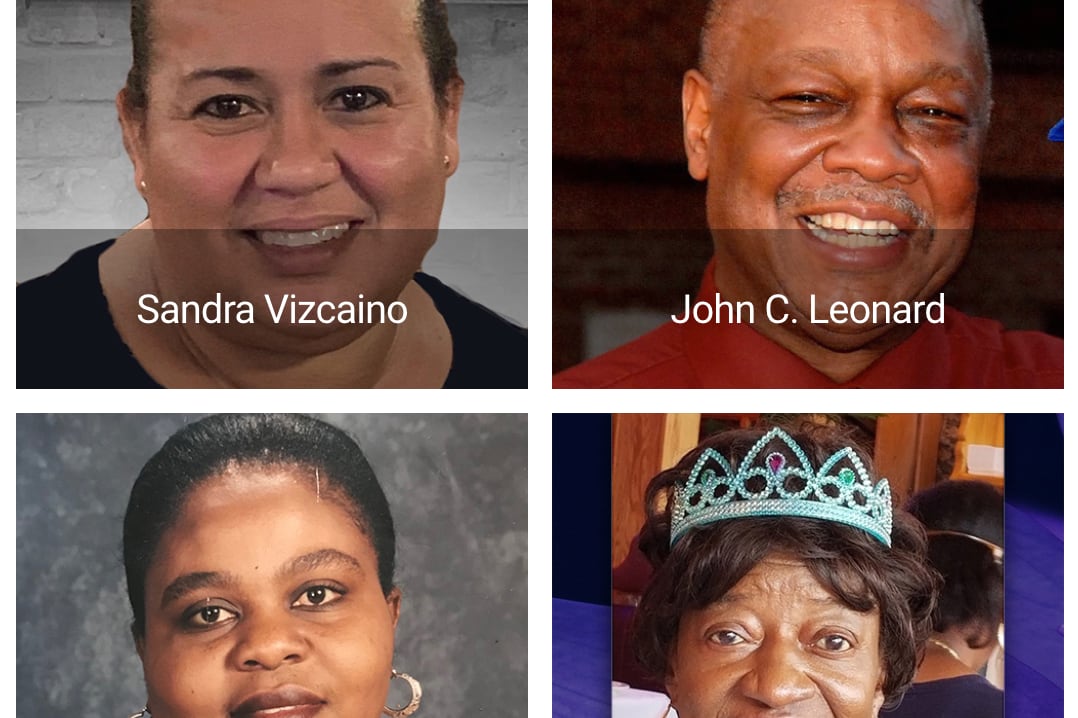

Among the education department employees who have passed away: 30 teachers, 28 paraprofessionals, four central office employees, two school administrators, two facilities staffers, two school aides, two food service workers, two school counselors, one parent coordinator, and one technology specialist.

Paraprofessionals, who are much more likely to be black or Hispanic than traditional classroom teachers and earn significantly less money, have been the hardest hit. They represent about 17% of the education department’s workforce, but 38% of its coronavirus-related deaths. That mirrors a stark divide across the city, as people of color have been disproportionately affected by the coronavirus.

Officials revealed which boroughs have seen the most fatalities of school-based staff: 24 school staff members who worked in Brooklyn schools have died; 19 in the Bronx; 14 in Queens; 9 in Manhattan; and 4 in Staten Island. That breakdown does not include three central office administrators.

They were not necessarily confirmed to be COVID-19 cases by the city health department. No names were released, and no details were given as to which schools the employees had worked in — though some elected officials have called on the department to release more detailed information.

The numbers do not include school safety agents, who are employed by the police department and certain school nurses who are technically not education department employees.

Statistics on educator deaths, which are now being released weekly, come after teachers and elected officials blasted the education department for refusing to release information on the number of deaths within its ranks, as other public agencies have. The education department’s handling of the epidemic is also the subject of an investigation by a city watchdog charged with overseeing schools.

Educators who have been claimed by the virus include: Sandra Santos-Vizcaino, a third grade teacher in Brooklyn described as an “amazing hugger”; Dez-Ann Romain, a Brooklyn principal who “gave her entire self” to students who had struggled in traditional high school settings; and Rosario Gonzalez, a 91-year-old paraprofessional who rarely missed a day of work.

“This is painful news for too many of our communities,” schools Chancellor Richard Carranza previously said in a statement. “We will be there to support our students and staff in any way they need, including remote crisis and grief counseling each day.”

Christina Veiga contributed