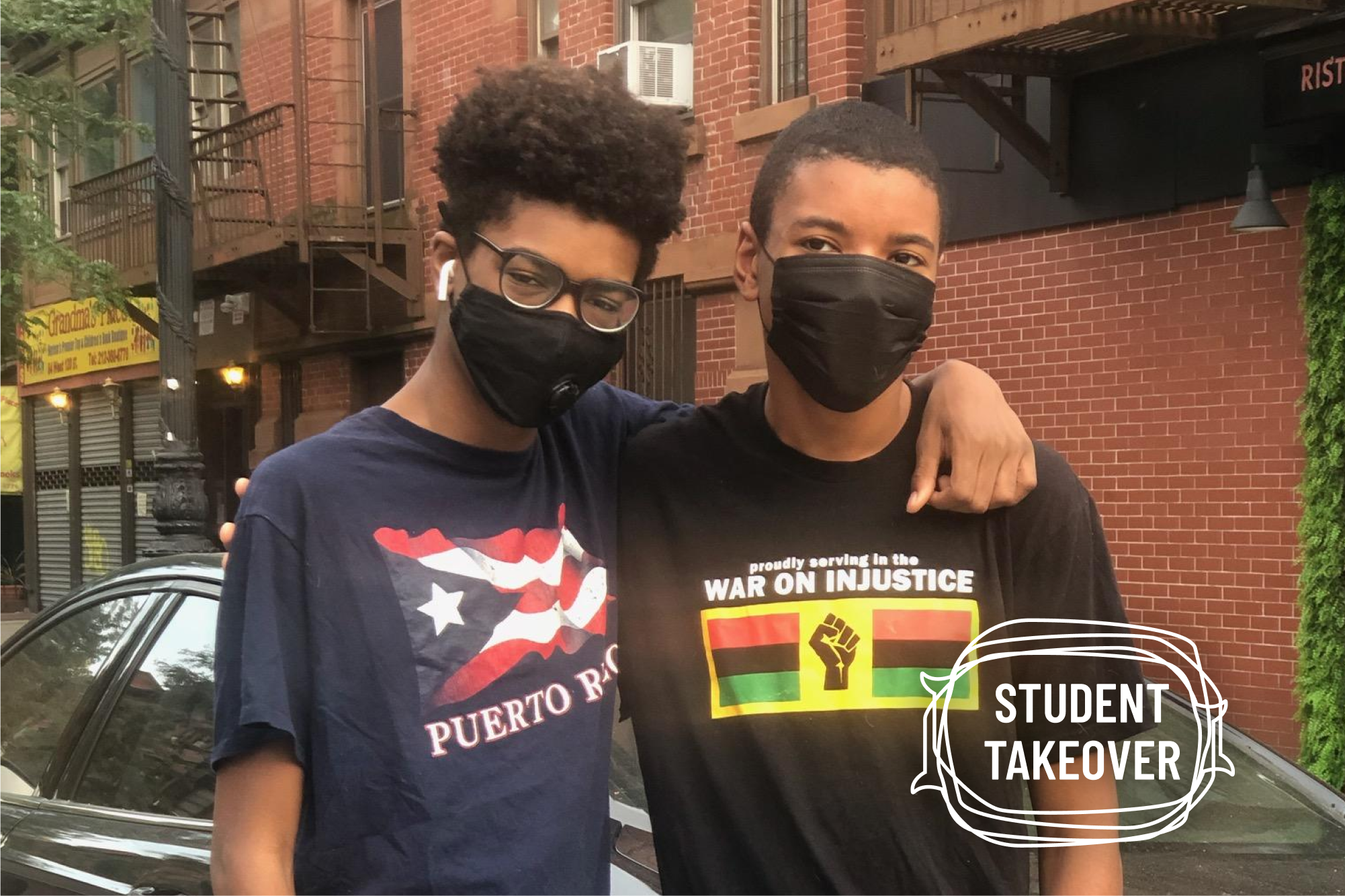

This personal essay is part of the Chalkbeat Student Takeover: a weeklong project meant to elevate the voices of students at this pivotal moment in America. Read more from the takeover here.

The night of June 1, New York City sent a text message to residents. A curfew was starting at 11 p.m. We were on our phones at the time, so we were the first to see the message in our household of six: the two of us, our two sisters, and our mother and father. Honestly, we were scared. We knew protests had been going on all around the country and curfews were in place in other cities. But New York? We were shocked.

After curfew began, we were taking out the trash and noticed that no one was outside. It was as if the city was sleeping. We noticed several cop cars moving slowly down our Harlem street, as if they were looking for people outside. This made us nervous. We realized the trust between us and cops is so very thin.

The fact that a Black person has to die in order for people to hear our voices is disturbing. We are scared because we are Black males in a country where being a Black male and getting killed by cops isn’t rare. Or, if we are not getting shot by police, we are being brutalized in other ways — by racial slurs and by systems we have no control over.

This is America.

A week later, our dad asked if we wanted to go to a protest in our neighborhood, Harlem. We were anxious and thought, what if something goes wrong? What if a riot breaks out? What if our family gets hurt in the process? And then we remembered that we’re all here for the same reason, to have police and the general community acknowledge injustices and police brutality against Black people. It’s an issue we can change.

We decided to make a protest sign out of an old cardboard box and thought about what we should write. Then it came to us: FIGHT THE POWER in big black letters. It’s a Public Enemy song we heard last summer in Brooklyn at Spike Lee’s “Do the Right Thing” block party. We thought of political injustice in America and the police systems that are set up against Black boys like us.

When we neared the protest, we were shocked because the crowd was massive. There was a speaker, and people were chanting What’s his name? George Floyd. What’s her name? Breonna Taylor. Honestly, we were a little nervous being in such a big crowd because of the risk of COVID-19 transmission and because of possible police violence. It took a while, but then we started chanting, too. We felt like we were part of something that was changing people’s perspectives.

We were so energized by the time we returned home. Our dad asked us what we want to see happen in the future. One of our sisters said she wanted to see a change in our laws so that cops can’t avoid being held accountable for their actions. To us and to all of the people protesting, this was our goal. And if we could tell our teachers, classmates, the community, and political leaders just one thing, it would be that Black lives matter.

Twin brothers Hunter and Hudson Russell-Horton, age 15, are ninth graders at West End Secondary School in New York City. They also serve as Teen Leaders with Read Alliance, tutoring first-grade students in reading. They thank their mother for inspiring them to write every day.