When David Banks was tapped with a group of local leaders to advise the mayor on how to reopen schools in the fall of 2020, he asked nearly two dozen principals for ideas.

A former principal himself, Banks laid out their concerns in a detailed memo about staffing and the need for timely information about safety rules. He grew frustrated when, three months later, Mayor Bill de Blasio twice delayed the start of the school year, citing some of the same problems that many principals had seen coming.

“There are no easy answers...but the failure here has been a failure to anticipate the obvious,” Banks told the Wall Street Journal at the time. Some task force members said the memo reflected deep relationships with principals and an understanding of the urgent questions school leaders were asking across the city.

Now, as the pandemic disrupts a third school year in the nation’s largest school district, Banks could soon be directly responsible for the system rather than offering advice from the sidelines: He is considered to be at the top of New York City Mayor-elect Eric Adams’ list for schools chancellor.

Adams has time to weigh his options before taking office on Jan. 1, and he could keep current Chancellor Meisha Porter in her role, though many observers expect him to appoint a new schools chief of his own. One thing is clear: As a key education advisor to Adams, Banks already is shaping the mayor-elect’s education agenda.

Banks, who declined to be interviewed for this story, is a natural choice to help Adams hone that agenda. He has a long track record as an educator, becoming the principal of a new Bronx school nearly a quarter century ago.

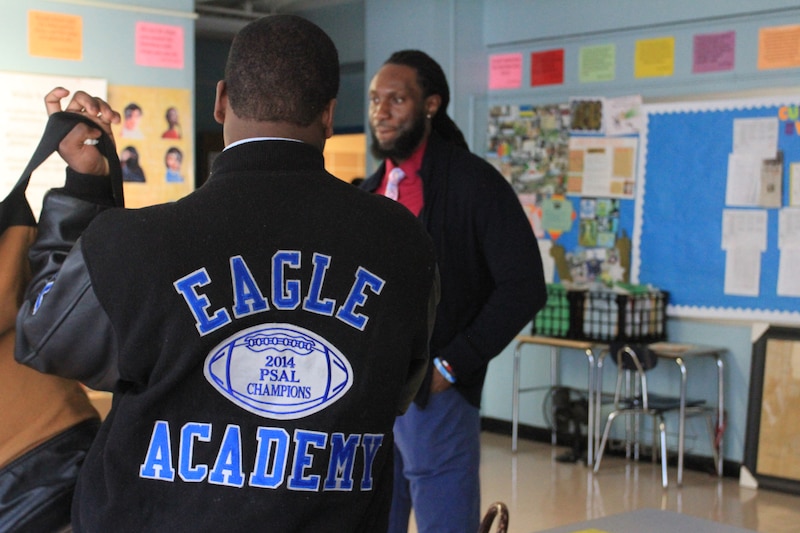

He helped launch the Eagle Academy, a group of public schools that boasts six campuses that almost exclusively serve boys of color, part of an effort to boost graduation rates and improve life outcomes for students who are often poorly served by the public education system. Banks now runs the foundation that helps provide training and support for those schools, such as college counseling, mentoring programs, and funding longer school days.

“He’s intensely, intensely passionate about this work, he’s deeply knowledgeable, and he’s also pragmatic,” said Mark Dunetz, president of New Visions for Public Schools, an organization that supports a network of district and charter schools. Banks is “the type of leader that I think a system as complex and large as ours needs.”

Banks, 59, has navigated shifting winds in education policy throughout his career. His profile rose during the Bloomberg administration, which was aggressively pursuing an education reform agenda — one that was gaining traction across the country — that called for closing low-performing public schools and opening new ones like Eagle Academy, and promoting the rapid growth of charter schools. Eagle Academy and Banks have won praise from some of the architects of that reform movement, including former Mayor Michael Bloomberg and former schools Chancellor Joel Klein.

Banks also has advanced ideas that have traction in progressive circles. None of his schools are charters, which have fallen out of favor among many Democrats, and he has advocated for the need to innovate within the strictures of union contracts. He was an early champion of infusing schools with culturally responsive curriculum and practices that celebrate Black and brown people, an idea that the New York City school system is now embracing.

“They were intentional about developing a positive self image in young people,” said Shael Polakow-Suransky, who was a senior education official in the Bloomberg administration and got to know Banks when they were both principals in the Bronx.

“They were way ahead of their time in terms of working on anti-racist approaches to education and doing it in a real, thoughtful, and sustained way.”

Perhaps most importantly, Banks has a deep relationship with Adams, according to people who know him, and his family is intertwined in Adams’ world. Banks’ partner, Sheena Wright, a nonprofit executive who leads the United Way of New York City, is co-chairing Adams’ transition team. Banks’ brother, a former senior police official, is advising Adams on public safety issues, the Daily News reported. And Adams has been a booster of Eagle Academy, appearing in a recent documentary about the schools.

“I think there’s chemistry there that allows that relationship to flourish,” said Dennis Walcott, a former schools chancellor under Bloomberg and current president of the Queens Public Library. Walcott pointed to their common backgrounds: Adams and Banks, who are both Black, grew up in working-class neighborhoods in Queens and Brooklyn and attended the city’s public schools.

He added: “Their DNA has been shaped on the values of the boroughs, the value of working class communities, and the value of education and what it has meant for each of them.”

Working-class roots in Queens

The son of a police officer and a secretary, Banks credits his parents with keeping him and his two brothers out of trouble and setting them up for success. When their Crown Heights block saw an uptick in crime during the 1970s, including burglaries in their building, and gang members trying to recruit other boys in the neighborhood, his parents moved the family to Southeast Queens, according to Banks’ 2014 book, “Soar: How Boys Learn, Succeed, and Develop Character.”

In their new neighborhood, Banks’ parents were determined to keep their children under their supervision and tried to make staying home as appealing as possible, buying pool and ping-pong tables and ensuring sleepovers happened at their house.

“They both sacrificed a lot of their own socializing, a lot of cocktails and card games and evenings out, for our benefit,” Banks wrote. “Moving to that block in Queens may have saved our lives.”

Banks enjoyed school growing up and had an early interest in teaching, though he decided to pursue a legal career. But within two years of graduating law school in 1993, he had enrolled in night classes and completed enough credits to be a school administrator. He became the assistant principal at P.S. 191 in Crown Heights.

Two years later, in his mid-30s, Banks would be given the chance to start a school from scratch. He wasn’t the most experienced candidate for the job, but his ambition and charisma impressed Richard Kahan, who at the time ran Urban Assembly, a nonprofit organization that was developing its first school and which now supports 23 schools across the city.

“He didn’t have anything like the experience or the track record of the others,” Kahan said, but “he was exactly the compelling person we wanted to hire.”

As the leader of the Bronx School for Law, Government, and Justice, Banks was excited by chances to promote hands-on learning. When a cigarette billboard went up across the street the school’s leaders designed a unit about it: studying the effects of nicotine in science class, estimating the distance from the school to the ad in math class, and researching tobacco laws in social studies class.

The school launched a letter-writing campaign to local elected officials, an effort encouraged by Porter, who then worked at the school and was mentored by Banks. City officials ultimately invited some of the students to a ceremony signing a law that banned cigarette advertisements close to schools. The ad on the billboard came down.

“That to me is what education is all about,” Banks wrote in his book, describing the episode as “the most successful month, educationally speaking, that I ever had.”

Building a network

Seven years later, Banks would get another shot at building a school from the ground up, a project that would mark the beginning of the Eagle Academy schools.

A civic group, One Hundred Black Men, was alarmed by a report that suggested a majority of the state’s prison population came from just seven New York City neighborhoods, including the South Bronx. The group, which counted Banks and his father as members, believed opening a school specifically for young men of color could help reverse those outcomes and improve their odds of graduating high school and going to college.

In 2004, with the support of then-Senator Hillary Clinton, the organization convinced the Bloomberg administration to greenlight the Eagle Academy for Young Men in the Bronx, according to Banks’ book. Banks would be its founding principal.

The Eagle Academy was part of a movement under Bloomberg aimed at giving families in under-resourced communities a wider array of schools from which to choose.

The Bloomberg administration closed many low-performing large high schools, replacing them with smaller ones that could offer a more personalized education. And they helped turbocharge the proliferation of charter schools, which are publicly funded but generally free of union contracts that include strict tenure, seniority, and work rules.

Banks has long been friendly to the sector, according to charter leaders, but he has also argued for the importance of running schools under the auspices of the school district. None of the Eagle Academy schools are charters.

“We did not want to open as a charter,” Banks told the Buffalo News in 2014. “We wanted it to be a public school and show that you could have an innovative school in a traditional public system.”

The Eagle Academy schools have embraced strategies to reach boys of color who have traditionally not been well-served by the city’s public schools, including extended school days to keep students engaged and out of trouble after regular hours. The schools also run mentoring programs and cultivate relationships with business leaders to serve as role models and expose students to career possibilities they may not have considered.

Banks has prized parent engagement, something multiple observers said could give him credibility in school communities if he became chancellor. To encourage attendance at PTA meetings, Banks held them on Saturdays every other month, two-hour long events that included meals, information about the school, and also seminars on topics like job hunting, according to his book.

At one point, Walcott, the former chancellor, was invited to attend one of those Saturday meetings in the Bronx and was blown away by the attendance. “That place was jam packed,” Walcott said.

The schools have also prized strict rules and high expectations, Banks has written, and has deployed practices such as strict uniform policies that are reminiscent of charter networks such as Success Academy or KIPP.

“We talk about how dressing in the style inspired by prison clothing — no belt, sagging the pants — sends a message about how you see your own future,” Banks wrote. “Like it or not, the world takes them more seriously.”

Students are also sorted into “houses” named after prominent figures of color, such as Roberto Clemente, W.E.B. Du Bois, or Malcom X, partly as a way to build camaraderie. But if an Eagle Academy student failed to turn in homework assignments, for example, they could lose points for their house, a fact that would be displayed for the rest of the school to see, Banks wrote in his book. (An Eagle spokesperson did not say if that practice is still used, and not all Eagle schools use the same approaches.)

Since 2004, the Eagle Academy network has grown to include six schools serving students in grades 6-12 — one in each of New York City’s five boroughs and one in Newark, New Jersey. Under the de Blasio administration, which has generally resisted large-scale school closures and openings, opportunities for growth have been limited. The newest Eagle Academy opened on Staten Island in 2014.

The schools have been popular with some parents, including Tanesha Grant, whose 14-year-old son Mandell attends Eagle Academy for Young Men of Harlem. Grant said she was impressed by the school’s commitment to weaving Black culture and history in the curriculum; her son was recently learning about Langston Hughes. As a single mother, she appreciates that many of the teachers are men of color. And she also likes that her son doesn’t have to pass through metal detectors on his way inside.

“I appreciate that Eagle Academy doesn’t paint Black people and Black culture as always struggling,” said Grant. As a parent advocate, Grant has previously fought for culturally responsive materials in a wider set of schools, but at Eagle Academy, they are already woven in.

Still, there are some signs that success has been uneven. Three of the five New York City schools are considered among the lowest performing in the state due to low achievement and growth scores at their middle schools, based on data from the 2017-2018 school year. And some of its schools have posted higher-than-average rates of chronic absenteeism. (State testing, and the state’s accountability system, have been disrupted by the pandemic so there have been no adjustments to schools’ accountability status in recent years.)

But the schools have generally posted graduation rates that are higher than the city average. In 2019, the Eagle Academy schools in Brooklyn and Queens posted graduation rates of about 90%, far higher than the city’s average that year of 77%. The network’s Bronx outpost had a lower graduation rate, at 71%.

Aaron Pallas, a professor at Teachers College who has studied school performance, said the test scores are just one data point and may not reflect the overall quality of the schools. “One can’t ignore test scores,” he said. But “there is a particular orientation to helping young men of color develop and that’s not necessarily going to be reflected in the test scores.”

From 6 to 1,600 schools?

It remains to be seen whether Banks’ could quickly move from supporting a small network of six public schools to supervising the largest school system in the nation, with responsibility for 1,600 schools and nearly 150,000 employees.

Over the last 20 years, the city’s schools chancellors have had widely varying backgrounds. Some have had little education policy experience but had high-level government management positions, including Joel Klein, a lawyer who ran the antitrust division of the U.S. Department of Justice and served as chancellor under Bloomberg.

More recently, de Blasio has selected leaders who have either had experience running big city school systems (Richard Carranza) or spent years rising up the ranks of New York’s education bureaucracy (Carmen Fariña and Meisha Porter).

Banks does not fall neatly into any of those categories; he has not supervised a large bureaucracy nor has he worked inside the system for long. The Eagle Academy Foundation, which Banks runs, aims to scale the Eagle model and support educators’ efforts around the country to reach students of color. (Its website says it has worked with 1,000 school leaders in 65 cities; an Eagle Academy spokesperson did not provide more details about the foundation’s work.)

“He would bring some knowledge of how the system works from the perspective of a school developer, but it seems like a potentially large step up in terms of the size and scale of running the city’s schools relative to what he’s been doing up until now,” Pallas said. “That’s not to say he can’t rise to the challenge, and no chancellor does it alone.”

Whoever takes the reins of the city’s school system will face enormous challenges, as the pandemic has interrupted student learning across three separate school years, with many students experiencing gaps in instruction and emotional trauma.

But there is also opportunity: The city is flush with nearly $7 billion in relief funding for education with more funding likely to come from the state. Adams has only revealed broad strokes of a schools agenda, perhaps allowing his schools chief to play a big role shaping it.

Banks sketched out some ideas of his own in the Daily News, including making better use of digital learning tools to give students access to experiences and educators outside their classrooms, investing in culturally responsive history curriculum, and moving away from an “overreliance” on standardized tests.

“We must not fall into the trap of doing more of the same,” he wrote. “We have never had a better opportunity, nor a more pressing need, to reimagine our school system.”