New York City officials are figuring out how to evaluate educators this school year, even as typical performance measures have been upended by the pandemic.

After New York became the epicenter of the country’s coronavirus outbreak last year, Gov. Andrew Cuomo issued an executive order in June pausing a state law that mandates school and district leaders formally assess teachers and principals each year.

Despite ongoing disruptions to classroom learning, the governor has not yet issued a similar order this school year, though a Cuomo spokesperson said the governor is still considering it. The state’s education department said they plan to ask the governor to put the evaluation law on hold, but have not yet done so.

In the meantime, New York City’s education department, in consultation with union officials, is drafting a revised evaluation plan to account for the pandemic. City officials did not release any specifics regarding their plans, saying that they were not yet final and will require state approval.

The evaluations offer a formal opportunity for administrators to provide feedback with the goal of improving teaching. That could be especially important this year as educators have had to adapt to unfamiliar platforms and methods of engaging students. These assessments also play a role in whether or not to grant teachers tenure and may also be used as grounds to fire educators. (In practice, very few teachers are denied tenure or terminated due to poor ratings.)

But implementing a revised evaluation system in the remaining four months of the school year could be tricky to pull off, and is already generating pushback from some educators and advocates. They point to the challenge of implementing the two key measures in a teacher’s rating — student assessments and in-person classroom observations — which have both been disrupted.

“Given the situation that we’ve found ourselves in over the past year, the unevenness of the experience of both educators and students makes it very difficult to employ the traditional instruments to evaluate educators,” said Paula White, executive director of the teacher advocacy group Educators for Excellence. “It’s very dicey.”

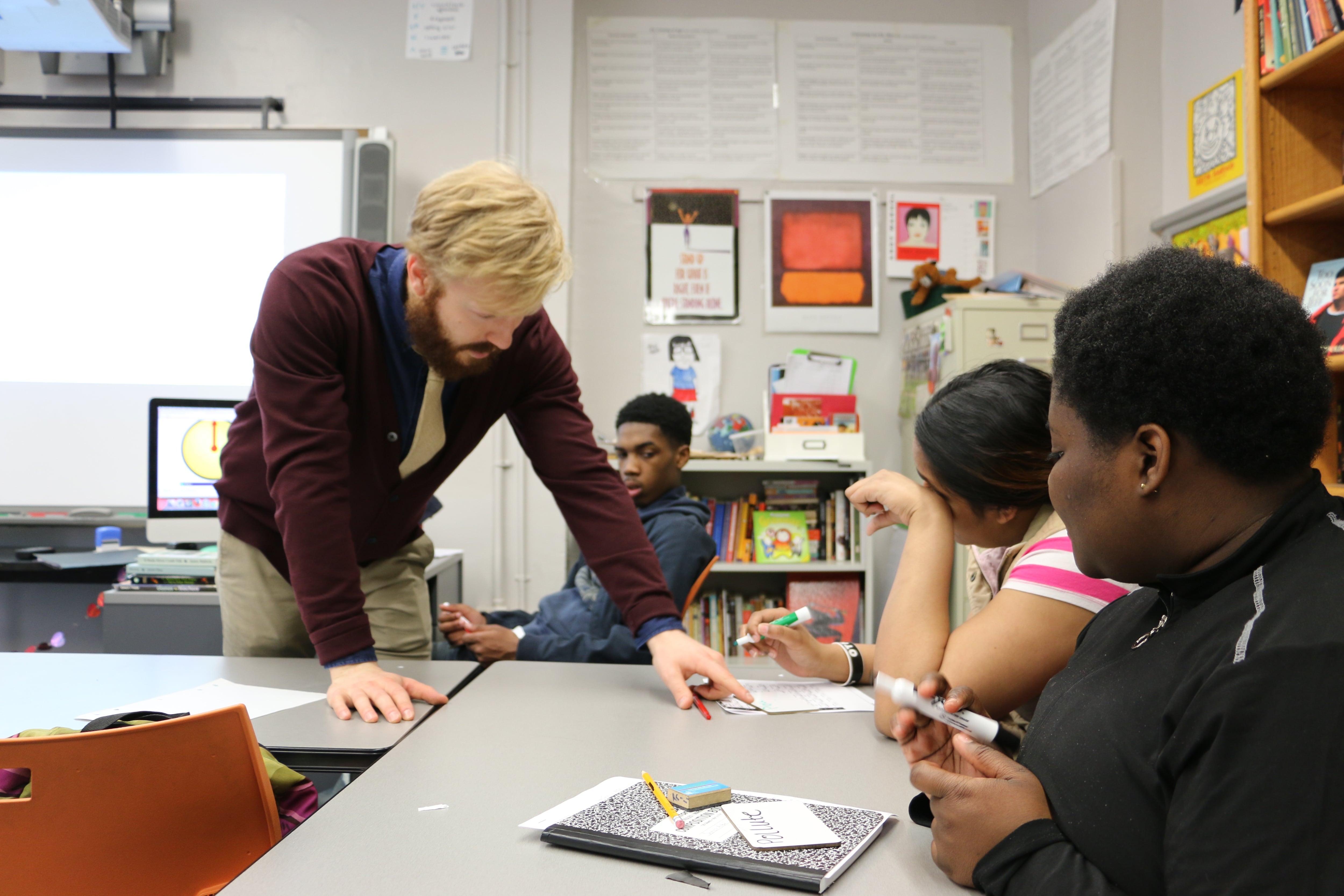

Traditional classroom observations were not crafted with virtual instruction in mind, and most educators are teaching remotely. The evaluations often pay close attention to the level of meaningful interaction and discussion among students, who may not be working as closely in socially distanced or remote classrooms, and the city has not communicated clear standards about what quality remote teaching should look like.

Complicating matters, many teachers have seen their classroom assignments shift this year, whether they’ve gotten new students or had to switch from in-person to remote, as high schools are fully virtual and middle schools buildings are reopening at the end of this month after being closed for three months.

Collecting student assessment data, the other main ingredient in teacher evaluations, is also a challenge. Some schools use state test scores, such as reading and math tests given in grades 3-8, which the state is seeking to cancel, or the Regents high school exit exams, a round of which have already been canceled. Schools may choose from a list of alternative assessments in lieu of those exams, but administering those tests remotely could prove difficult and the results could be unreliable, especially if a significant slice of students don’t take them.

Still, spinning up virtual evaluation systems in the pandemic is not without precedent. In Newark, for instance, district and union officials hammered out a framework for conducting virtual observations, which could include assessments of how effectively teachers are using online “breakout rooms” to target instruction or using screen-sharing to display high-quality work.

In New York City, union officials have also participated in negotiations over the evaluation process, though they have emphasized that deploying a revised system at this point in the school year is not ideal.

“We are being held to the state law for teacher evaluation even though we are already halfway through the school year and our members have so much else on their plates,” officials at the United Federation of Teachers wrote to school-based chapter leaders this month. “The UFT’s goal in its talks with the DOE was to make sure the evaluation plan reflected the unique circumstances and challenges facing teachers this school year.”

A city education department official said “timelines will be adjusted accordingly” to make sure there is enough time for evaluations to be conducted.

Regardless of the formal evaluation system, many school administrators have been providing informal feedback to teachers.

“Evaluations are just part of what’s going on in a school — that’s something that should have been happening,” said Matt Brownstein, an assistant principal at P.S. 330 in Queens.

Still, he worries about whether formal teacher assessments could be fair this school year. Administrators often look for signs of engagement by watching whether students are tracking their teachers, for instance, or based on informal conversations with students in the class. That is difficult to pull off remotely — and in person, a teacher might struggle with engagement if there are just one or two students in the room.

“We can get information by looking at practice, and we can get information by looking at assessments,” Brownstein said. “But to use it to judge teachers in the traditional way is unfair.”