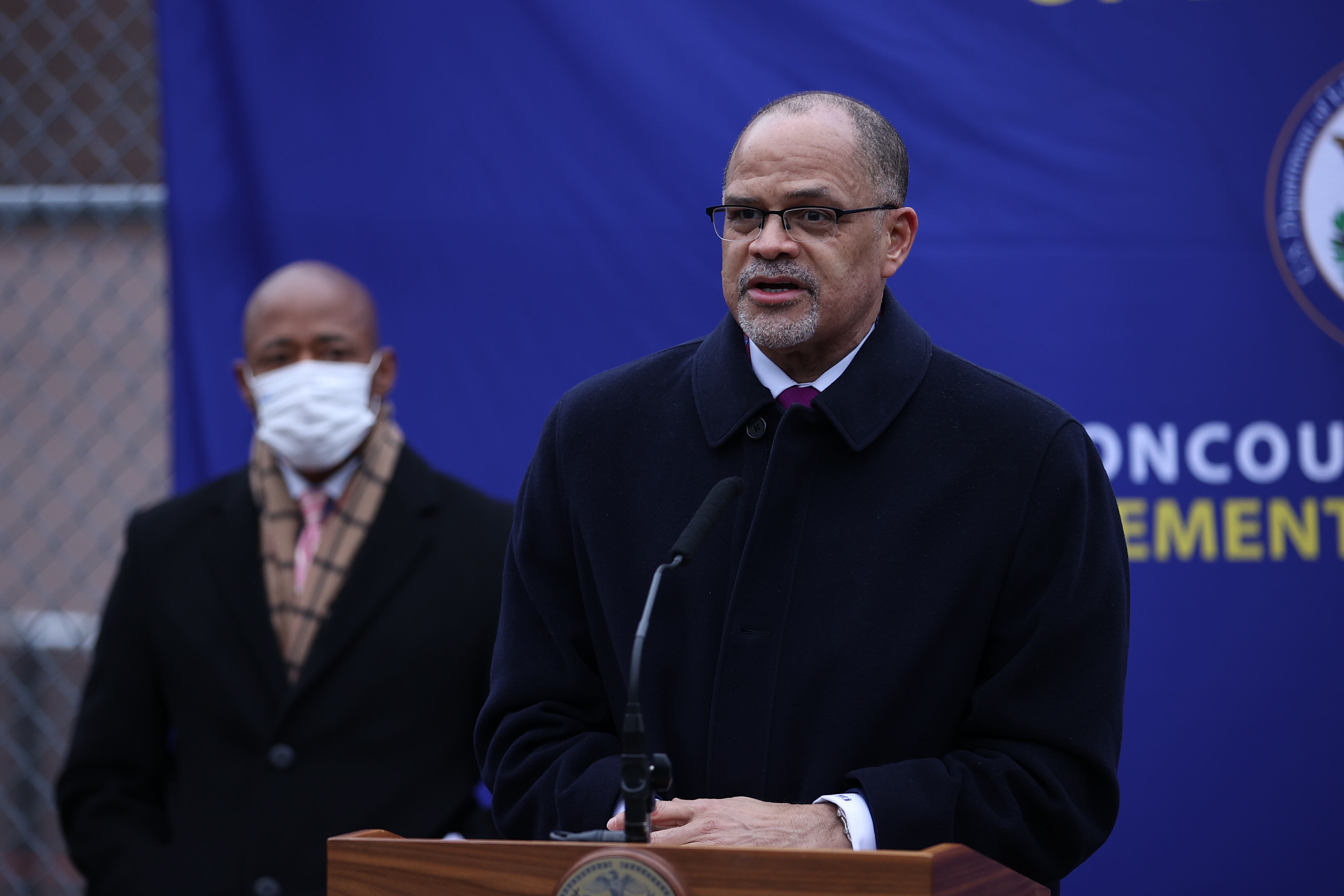

New York City officials are planning to open a new school focused on serving students with dyslexia, Chancellor David Banks said Wednesday.

Banks made the announcement during a virtual, education-focused state budget hearing, after Bronx Assemblyman Michael Benedetto asked for Banks’ thoughts on screening young children for learning disabilities.

“I’ve met with many other advocates around the city. We’ve worked very closely around the creation of a school, specifically a public school that will be dedicated specifically for kids with dyslexia — be the first time that we’ve had it in New York City,” Banks said. “And so you’ll hear in the coming weeks more about that new school.”

Banks added that Mayor Eric Adams wants such a school “in every borough.”

An education department spokesperson declined to offer more details, including where the school would be located, what grades it would serve, and how students would be admitted. If the new school comes to fruition, it would be the first district-operated school and the second public school in New York City to focus specifically on students with dyslexia. The first, Bridge Preparatory Charter School, opened in 2019.

The chancellor’s comments suggest that addressing gaps in the city’s approach to reading instruction may be one of the administration’s early priorities. Advocates and experts have argued for years that the city has no systematic approach to reading instruction, leading to scattershot approaches at individual schools that often fail to properly serve students who struggle to master the relationships between sounds and letters, one of the hallmarks of dyslexia.

At the same time, an increasing number of students with disabilities, including those with dyslexia, have left the public school system entirely, winning hundreds of millions of dollars worth of tuition reimbursements from the city. That process tends to favor families with time and resources. (In 2019, 16% of the city’s students with disabilities were proficient in reading in grades 3 to 8, compared with 56% of general education students, according to state tests.)

Frustrated with the city’s approach, some parents have been working to launch a public school specifically designed to adopt best practices in teaching students with dyslexia. A group of parents applied to launch such a school in 2019 as part of a flashy effort to open 20 new schools, though that program appears to have stalled during the pandemic and none of those schools have been publicly announced.

Naomi Peña, the parent council president in Manhattan’s District 1 and part of the parent group working to launch a school geared toward students with dyslexia, said the parents met with Banks in October, before Adams officially won election. “We presented our model, we presented our idea, and he liked it and even had some more feedback,” she said. It was not immediately clear if the new school Banks mentioned on Wednesday is the same as the one outlined in the parent group’s proposal; a department spokesperson declined to comment.

“If they do tap us, we are ready,” said Emily Hellstrom, another parent involved in the project. The group has been in continuous talks with the education department and has been working to line up partners to help provide teacher training, even though the city has not formally greenlit their proposal. “It is so refreshing and exciting to hear the chancellor speak in these terms.”

On the campaign trail, Adams repeatedly mentioned struggling with a learning disability of his own and said he supported universal screening for dyslexia. Some state and city lawmakers have long pushed for more screening, including during Wednesday’s hearing.

Under former Mayor Bill de Blasio, officials set plans to screen about 200,000 students in kindergarten to second grade to see if they were struggling readers. While the screens don’t test for dyslexia, literacy experts said they can identify gaps that are associated with dyslexia, Chalkbeat previously reported. That plan was part of the city’s $635 million plan for pandemic-related academic recovery, almost entirely funded by a portion of the $7 billion federal COVID relief dollars for New York City’s school system.

Banks previously indicated that opening new schools will be a component of his administration’s approach as a way to replicate models that are doing good work. The chancellor recently visited The Windward School, a private program that specializes in reaching children with reading challenges, as part of a tour with Brooklyn Assemblyman Robert Carroll, who has advocated for universal dyslexia screening.

“I’m looking in as many places as I can for innovative and dynamic solutions to the pressing issues facing our children and school system,” he said in a statement at the time.