New York City is moving forward with plans to launch two virtual schools that will serve ninth graders only next year, officials recently revealed.

One of the schools will have a “heavy” career and internship focus while the other will be “completely remote,” said Carolyne Quintana, deputy chancellor for teaching and learning, during a virtual meeting last week with the NYC Coalition for Educating Families Together, a parent advocacy group.

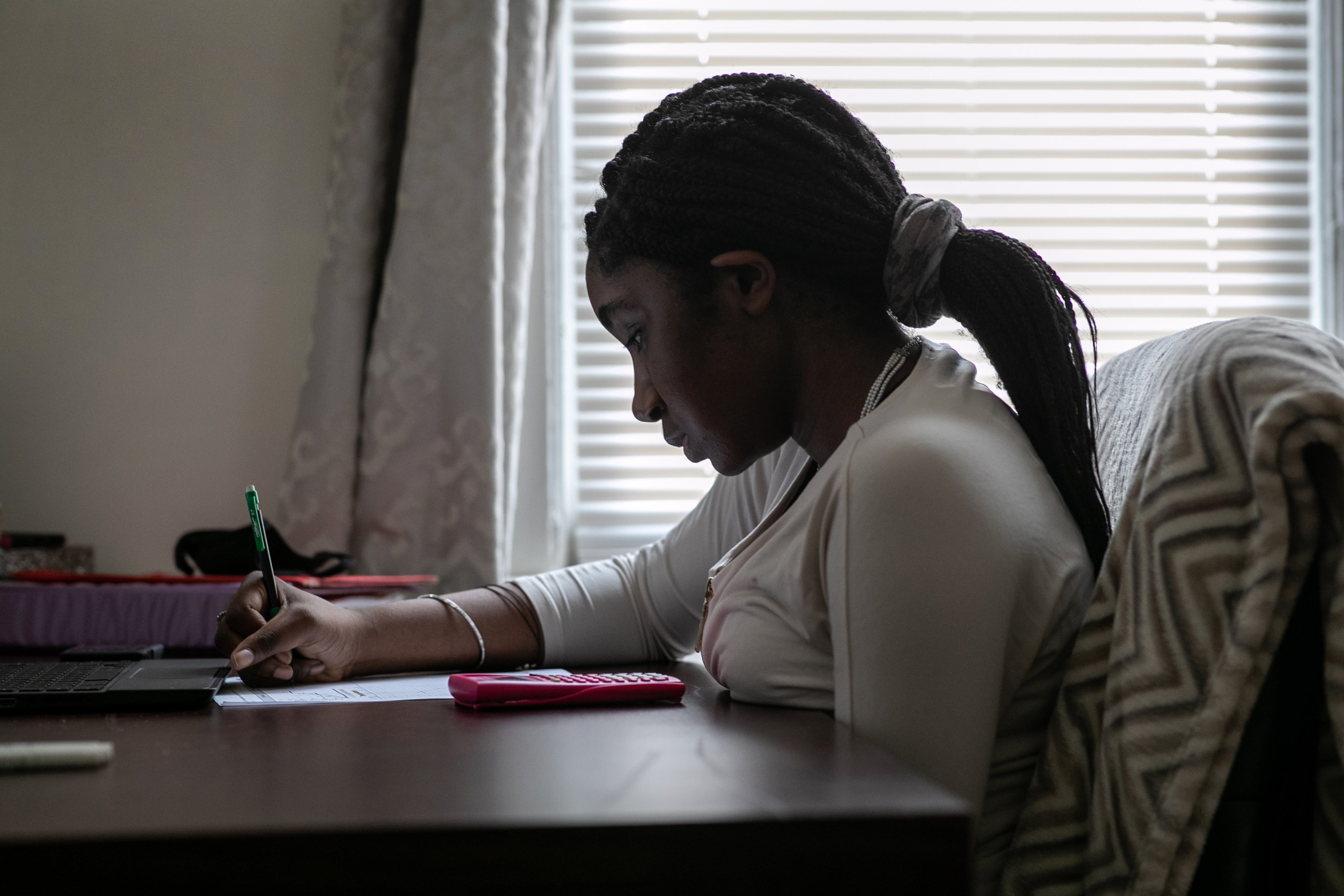

“Those virtual school options are for students who may need to work from home, whether it’s for health reasons, for socio-emotional reasons, [or] maybe they were more successful that way,” she said, adding that the city is “working with partners to get that done.”

The city plans to eventually expand the offerings to include middle school students, Quintana noted, though she offered no timeline. The department did not want to create a virtual option for elementary students for now since that would require a caregiver to stay home, she said.

Since taking office in January, schools Chancellor David Banks has repeatedly said that he sees a greater role for virtual instruction even absent the COVID pandemic, arguing it could give students access to a wider range of quality learning experiences.

But he has yet to share the specifics of that vision, and many unanswered questions remain about the city’s two forthcoming virtual programs. Among them: how will they be structured, what will the curriculum be, and how can families enroll. The regular high school application process has concluded, though students have not yet received admissions offers.

Tom Liam Lynch, who runs the InsideSchools online guide, said it is crucial for the city to provide information to the tens of thousands of rising ninth graders who are expected to soon receive high school admissions offers and may want to consider a virtual option.

“The onus is on the administration at this point to formally share those specifics so families can start to wrap their heads around what the fall might look like for their children,” he said.

Providing students some virtual offerings a la carte, such as computer science or AP classes, as the city has previously tried, would be relatively easy to quickly launch, Lynch said. But launching a full-time virtual option is a much heavier lift.

Education department officials declined to answer questions about the virtual programs and have not said who will staff them or even if they will launch by the first day of school in September. Nathaniel Styer, a department spokesperson, said more details will be shared “soon.” The city’s teachers union said last month that they had “initial conversations” with the city about virtual teaching, but did not yet reach any concrete agreements.

“We’re still awaiting further discussions with the DOE,” a union spokesperson said Wednesday.

Jennifer Goddard, a Brooklyn mom who asked Quintana about virtual options during last week’s meeting, said she was disappointed to learn they would only be available for ninth graders.

Her 10-year-old son, who has asthma and an overactive immune system, has been enrolled in the city’s program for medically fragile students, which only provides one hour a day of instruction. Goddard said the education department instructor her son works with during that hour is excellent, but she still spends hundreds of dollars a month on supplementary instruction from a company called Outschool. She had hoped the city would provide a full-fledged remote learning option this fall.

“I want him to be in school and make new friends,” Goddard said. “[But] it’s a choice between a child’s health and their education, and it shouldn’t be that way. It fills me with dread to have to make this decision again.”

Banks initially suggested he was open to creating a remote learning option as the omicron wave exploded this winter, but that never materialized, frustrating some parents who were fearful of COVID exposure in school buildings. More than 175,000 students and 56,000 staff have tested positive this school year, according to city data.

New York City is one of just a handful of large school districts that did not provide a virtual option this year. Philadelphia and Detroit created virtual academies during the pandemic. Los Angeles, the nation’s second largest school district behind New York City, plans to launch new virtual schools this fall. But for some districts that ran virtual academies separately from their regular schools, there was less interest in them, in part because there were fewer opportunities for students to interact with their classmates and teachers.

In New York City, it’s unclear how much demand there will be for virtual options this fall, though limiting them to ninth grade will significantly narrow the potential pool of students. If the programs are popular, and as they expand to middle school, significant tradeoffs could arise.

The city’s public schools (excluding charters) have seen enrollment slide about 6.4%, or roughly 64,000 students, since the pandemic hit, and new remote offerings could further drain students — and funding — from brick-and-mortar campuses. Such attrition could increase pressure to close or merge schools. On the other hand, the virtual programs could help keep some families in the district who might otherwise have considered other options.

Whether remote options will work well for students remains murky. Research has linked online learning to worse test scores. Students who learned remotely last school year tended to do worse academically than students who were in person, according to two studies. Even those who voluntarily chose virtual schools before the pandemic tended to experience lower test scores and graduation rates.

Still some argue that an online option can help prevent students from dropping out or provide needed options for students who were bullied or have medical needs. New York City officials initially suggested that virtual options could help battle chronic absenteeism, which has surged this school year. And some parents reported that their children thrived with remote instruction.

Quintana acknowledged that officials aren’t sure how many students will be attracted to future virtual offerings but said parents “should be able to choose and be supported” if they wanted a remote option.

“There are some folks who are absolutely opposed to this — it’s not for them,” she added. “And for the folks who absolutely need it, it is.”

Matt Barnum contributed

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.