Moe Sanders is about to become the first in her Bronx family to graduate from college.

The rising senior at Skidmore College initially planned to pursue a career in publishing, but now she’s preparing to become a college counselor.

She wants to help other first-generation college students like herself, inspired by those who helped her in a summer bridge program organized by Urban Assembly, a nonprofit that runs a network of New York City public schools.

In Urban Assembly’s summer bridge program recent high school graduates get coaching around the transition into college or other career-oriented paths after graduation. Coaches are recent alumni who attended the same high school just a couple of years before.

Research has shown that this peer-to-peer model is highly effective, and it’s offered by many organizations in New York City, a school district where more than 70% of students come from low-income families.

For many low-income and first-generation college students, the summer before their first year of college is nerve wracking. Between endless paperwork and financial aid decisions, some students never matriculate.

This is a phenomenon known as “summer melt,” which refers to high school graduates who apply, are accepted, and commit to a college, but never make it to campus in the fall. These students intend to attend, but something happens in the summer that leads them to “melt.”

Although it’s unclear how many New York City students are impacted by summer melt, research shows that nationwide up to 40% of low-income students who intend to go to college every year don’t make it to school in the fall.

Bridge programs can make a difference

As a Black girl attending high school in one of the poorest neighborhoods in New York City, Sanders felt the odds were stacked against her. After graduating from the Bronx Academy of Letters, an Urban Assembly high school, Sanders relied on the support from her coach as she headed off to Skidmore College, located in Saratoga Springs, N.Y.

Having benefited from a coach, Sanders wanted to pay it forward. The summer after her freshman year of college, she became a coach herself and started supporting younger students.

“That’s when I kind of started my job as what I like to call a mini college counselor,” Sanders said.

And she hasn’t stopped. This is her third summer as a coach.

Urban Assembly is one of many bridge programs that try to prevent New York City’s students from “melting.” Their alumni are 90% Black and Latino, and 86% are from low-income homes. Among its summer bridge participants, only 12% “melt.”

The program, founded in 2008, hires recent alumni coaches to work 20 hours per week for 13 weeks during the summer months. While they coach recent graduates, they also receive training, mentorship, and professional development in topics such as financial literacy and time management. They practice leadership skills while modeling what life could be like after high school.

Stephanie Fiorelli, the group’s director of alumni success, said they hire one alum per high school to coach the senior class from May to August. “They’re kind of near peer mentors, and they pick up where the guidance counselors left off.”

The program empowers recent graduates to make their own decisions. “A lot of what we do in this bridge program has helped students feel that they have control over the choices they’re making,” Fiorelli said. “A lot of times students won’t persist in college or in job training programs because they feel they didn’t really get to make the decision for themselves. So, the coaches learn how to give them all options.”

Because a lot of the transition steps happen in the summer, it can be an overwhelming time for a lot of recent graduates.

Jay Champagne, deputy director of alumni success, said many students struggle with the financial aid process, especially those whose families have a tenuous relationship with money.

Champagne said sometimes coaches get on the phone with financial aid officers to help advocate for the recent graduates. “If you’re at the age of 18, 19 and you’re trying to figure out financial aid, it’s very intimidating.”

It’s even more complicated when students are selected for extra verification from colleges, said alumni success coordinator Angelina Lorenzo. Verification requires students to submit additional documentation to prove a student’s financial status. “They say financial aid verification is selected randomly. But we’ve seen that 99% of our students end up getting flagged for verification.”

Lorenzo, an Urban Assembly alumni herself and former bridge coach, said she has witnessed students being asked for proof that a parent is on food stamps or for a sibling’s birth certificate. And coaches are trained to support students in such situations.

But the role of coaches goes beyond supporting students going to college. They are also able to support those transitioning straight into the workforce.

Jade Hooker, a recent graduate of Urban Assembly Institute of Math and Science for Young Women, is joining the U.S. Air Force. She wants to work with airplanes, and soon she’ll start training in aircraft maintenance. Before that, she’s enjoying the summer and preparing for what’s ahead.

“[Having a coach is] helpful because it’s basically the support system that you need. And they are able to give you resources or maybe get you in contact with other people that are thinking about doing the same things that you want to do,” Hooker said.

Bridge year-round

While Urban Assembly’s bridge program focuses on the alumni from the Urban Assembly high schools, other nonprofit organizations offer bridge training to a variety of public schools. One of them is provided by College Access: Research & Action, or CARA.

Founded in 2011, CARA trains coaches to work with students using the peer alumni model. Their program lasts the whole academic year, which means that coaches start working with students at the beginning of their senior year in high school.

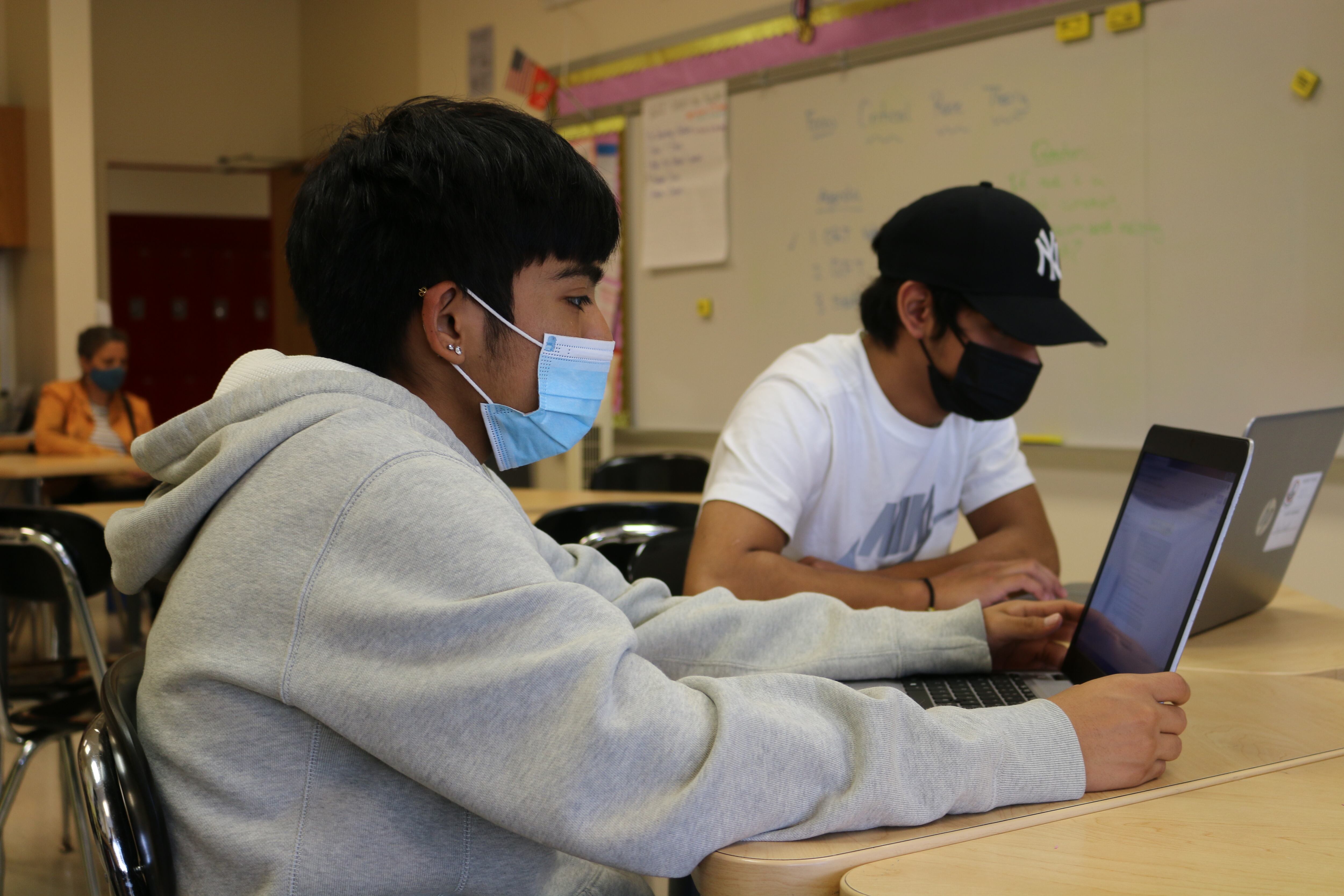

CARA coaches work 10 hours per week year-round. They work at school buildings and hold workshops with their cohort on topics ranging from financial aid to imposter syndrome, a pervasive feeling of self doubt many first-generation college students experience.

Deneysis Labrada, director of the bridge program, said coaches also help first-generation parents understand more about the college process.

“It’s not only the students who don’t know about the college application process. The majority of the families are coming from other countries where the application and college system is very different from the U.S.,” she said. “They have no idea what it means to apply to college, apply to financial aid, and all the scholarship opportunities that New York offers.”

Labrada also said that the majority of New York City high schools don’t have a counselor solely dedicated to college and career. Rather, they have one guidance counselor that is dealing with student mental health and schedules and registration in addition to college counseling.

“For those schools that have one guidance counselor, having a bridge coach is a whole extra person focusing on college and career,” Labrada said.

In addition to that, due to the coronavirus pandemic, many colleges and universities have transitioned their admissions and financial aid offices into a remote system, Labrada said. Many of CARA’s bridge students are struggling to reach officers, saying that they are often on vacation or don’t answer phone calls.

“Some colleges are not necessarily supporting incoming students as structured as they did in the past. Many graduating seniors right now are getting frustrated because they’re not getting answers,” Labrada said. “Our coaches are coming in and trying to close that gap too, and trying to support however they can.”

Bridge coaches develop leadership skills

CARA coach Nyeisha Mallett is an incoming senior at the Cooper Union School of Art in New York City. She attended Medgar Evers High School in Crown Heights, where she didn’t have the opportunity to participate in a bridge program.

She learned about the coach position through her cousin, and she joined the program during her first year of college. She’s currently finishing her third run as a coach.

“[This job] wasn’t something I planned to do, but definitely something important. And I like to do important things,” she said. “If I’m going to do something, I want to make sure that the time that I’m spending is important to somebody else.”

Mallett said her work goes beyond helping students with paperwork. Her role includes encouraging them to be as informed as possible about the decisions they’re making. One example she said comes up often among students is understanding the cultural shock of going from a high school that is predominantly people of color to predominantly white institutions, or what’s referred to as PWIs.

“We talk a lot about PWIs. I go to a PWI, and it’s still hard to navigate. For students of color who might have a hard time understanding that transition, it’s important to have those conversations with them,” she said.

“There are times where students come to me and they’re like, ‘What is your experience like? And I’m real about it. I went to an all Black Caribbean school. So it was a huge shock to me that I’m still navigating right now,” she said. “I tell them the experience about being the only Black person in the class. I want to make sure that they are aware that that could happen.”

If Mallett were a high school senior now, she would’ve been able to sign up for the city’s department of education bridge program. This year, they are offering a “next step texts” program, where alumni coaches support recent graduates via texting. Students from any public school can participate.

Bridge programs not only support high school graduates to transition into life after graduation, but also they offer a job opportunity to young adults that allows them to explore a career in the education field.

Sanders, the rising senior at Skidmore, has fallen in love with supporting other students who came from the same background as her to succeed after high school.

She said she loves working with students who want to take big leaps to better themselves through education.

“I see how important this work is, especially as a Black woman coming from a low-income area. People don’t believe in us. Even being in [predominantly white institutions], people still don’t think Black students and students of color can do it,” she said. “To be a part of that process for other students is kind of magical.”

Marcela Rodrigues-Sherley is a reporting intern for Chalkbeat New York. Contact Marcela at mrodrigues-sherley@chalkbeat.org.