New York City public schools issued significantly more suspensions during the first half of this school year, according to long overdue department statistics.

Between July and December 2022, schools issued just over 10,600 suspensions — 27% more than the same period in 2021. The number is about 6% higher than in 2019 just before the pandemic hit, even though the number of K-12 students has declined over 10%.

Drilling down into the data, principal suspensions — which last five days or fewer — jumped by about 29%. Superintendent suspensions, which stretch longer than five days, and are served at outside suspension sites, spiked by 21%. (The figures do not include charter schools.)

Before the pandemic hit, suspensions were on a downward trajectory, owing in part to a slew of policy changes that made it more difficult to exclude students from classrooms. When COVID forced the city’s school buildings to shutter, suspensions mostly stopped.

Last school year — the first time students were required to attend school in person since March 2020 — suspensions ticked back up but remained far short of pre-pandemic levels. That surprised some student discipline experts, who expected a larger increase given widespread concerns about student mental health and students’ ability to reacclimate to regular classroom rules.

Educators may have been more reluctant to exacerbate learning loss after years of pandemic schooling. Skyrocketing rates of chronic absenteeism and declining enrollment may have also played a role, as there were simply fewer students in school buildings to suspend.

Social distancing rules could have made physical confrontations, which may lead to suspensions, less likely. Suspensions are disproportionately issued to Black students, and teachers may have tempered suspensions in the wake of the racial reckoning after George Floyd’s murder.

Whatever the cause of the decline after the pandemic, suspensions are now ticking back up, mirroring educator reports across the country of more disruptive student behavior. Local data for the full school year, including demographic breakdowns, will not be available until later this year.

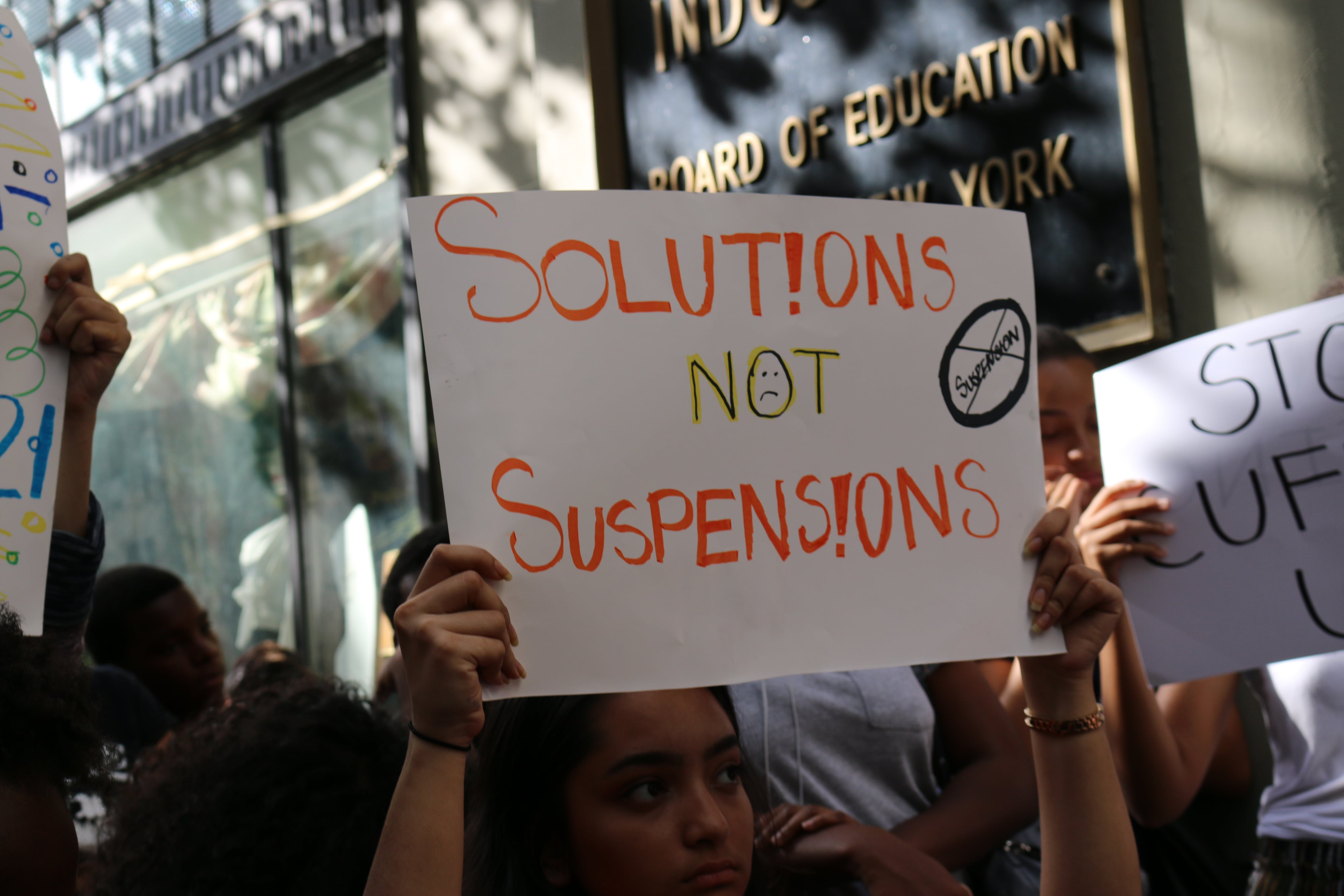

The uptick in suspensions raised concern among some discipline reform advocates.

“That is a huge problem that the city is choosing to increase the use of punitive and exclusionary approaches,” said Dawn Yuster, director of the School Justice Project at the nonprofit group Advocates for Children. “We are in the midst of a youth mental health crisis and we know our young people are literally crying out for more support.”

Jenna Lyle, an education department spokesperson, emphasized that the use of suspensions have generally declined over the last decade.

“We are continuously focused on equipping schools with the resources they need to address any issues in a positive, supportive, and less punitive manner, including through implementation of restorative practices,” she wrote.

Under city law, the education department’s mid-year suspension report is due by the end of March. Despite multiple requests, education department officials did not provide the suspension report for weeks. Lyle did not answer a question about why the city did not provide the figures within the required timeframe, a deadline the city regularly met before the pandemic.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.