Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

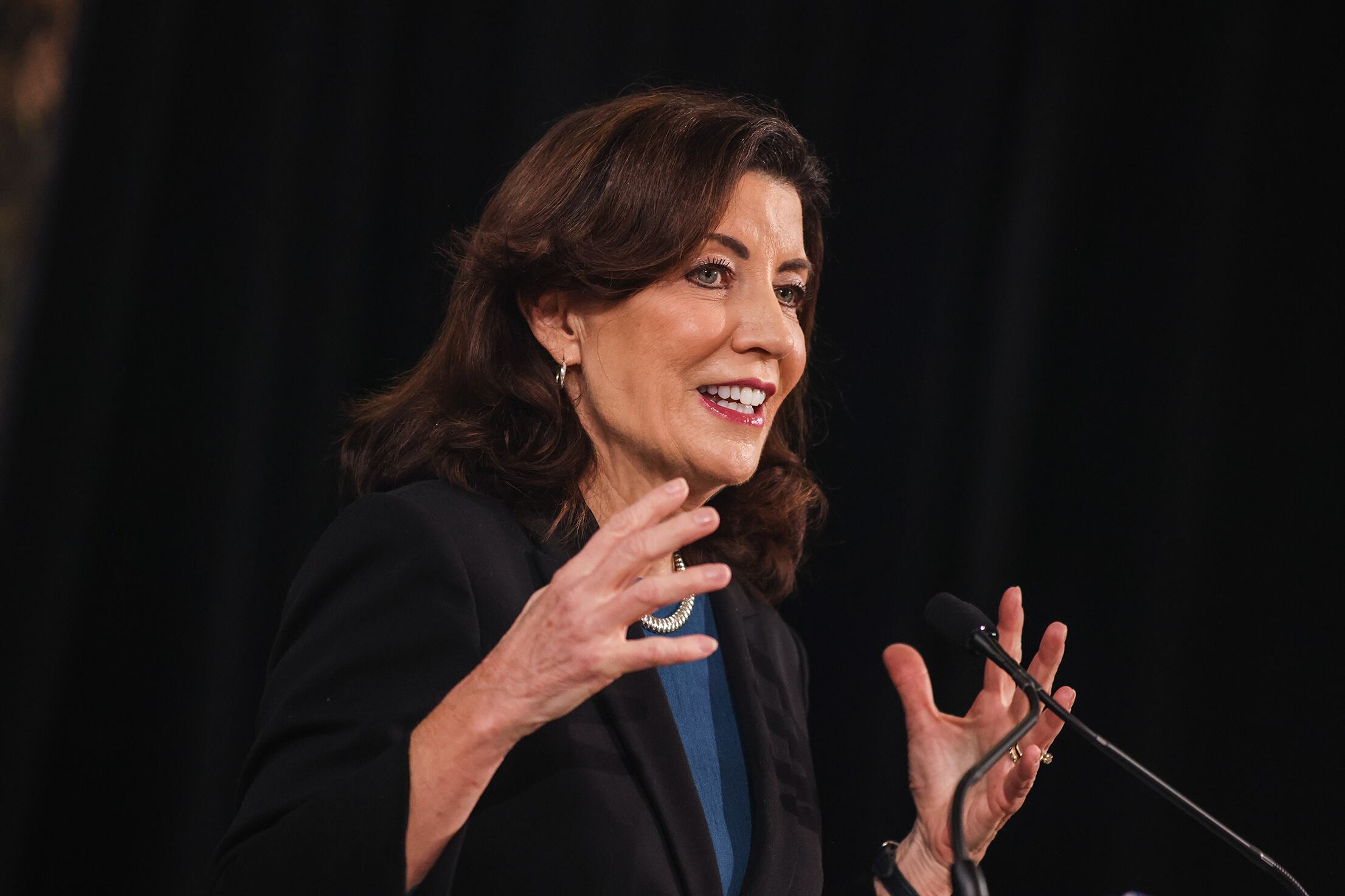

Eight months after New York City announced a major literacy shakeup, Gov. Kathy Hochul sketched out one of her own on Wednesday that may encourage districts across the state to adopt new reading curriculums.

The effort comes amid growing pressure for officials to boost literacy, as dozens of states have enacted efforts to improve reading instruction and embrace what’s known as the “science of reading,” an established body of research about how children learn to read. New York is one of a handful of states that has not advanced similar proposals in recent years, even as fewer than half of students in grades 3-8 are considered proficient in reading on state tests.

Hochul said her goal is to move schools away from “balanced literacy” — including a popular curriculum developed by Teachers College professor Lucy Calkins that has come under intense scrutiny in recent years. The approach includes mini-lessons and lots of independent reading time to get students excited about literature and help practice reading skills on their own. Experts say that method often does not work for students who struggle to read, including those with learning disabilities like dyslexia.

The state will begin to favor programs that emphasize phonics lessons that explicitly teach the relationships between sounds and letters, an approach backed by research. Hochul indicated her plan would help rid schools of discredited methods often found in balanced literacy programs, such as encouraging children to use pictures to guess at a word’s meaning.

“We’re going to throw away the old methods: Say goodbye, it didn’t work, and get back to basics,” Hochul said during a press conference at an elementary school in Watervliet, New York.

The governor’s proposal is unlikely to force changes in New York City because the city’s Education Department already launched its own sweeping curriculum mandate that appears to line up with Hochul’s plan. It remains to be seen whether the governor’s proposal will lead to big changes in other parts of the state, especially as curriculum overhauls can be difficult — and expensive — to pull off.

The state’s power is also limited, as local school districts are responsible for choosing their own curriculum materials. A Hochul spokesperson suggested the state’s plan would require that science of reading principles would need to be “part of” a district’s offerings.

“I think she’s trying to appease people who have heard about the quote unquote ‘reading crisis’ but is being very careful not to step on districts’ toes,” said Jennifer Binis, a long-time curriculum designer who has worked with teachers in New York State.

Hochul’s plan would direct the state Education Department to create a series of “instructional best practices” related to literacy skills including phonics, decoding, and comprehension. By September 2025, school districts would be required to certify that their curriculums, instruction, and teacher training efforts aligned with those best practices, according to a press release. (Officials declined to provide the exact legislative language Hochul supports.)

The governor also proposed a $10 million partnership with the state’s teachers union to train 20,000 educators and to expand efforts from the city and state university systems to help educators learn about the science of reading, a priority among state officials.

Hochul’s plan won support from union officials, advocacy groups, and a flurry of lawmakers. The state’s Education Department declined to comment directly on the proposal until more information about it is available. Some experts said they were happy to see Hochul emphasize literacy instruction, but remained skeptical that her proposal would lead to significant changes.

“It’s the beginning and it’s a good step,” said Susan Neuman, a reading expert at New York University and former federal education official.

But she said it’s “unrealistic” to expect deep changes in classrooms without a more significant commitment to rigorous training, money for new materials, and clear accountability mechanisms. “Unfunded mandates don’t work,” Neuman said.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.