Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

A few weeks ago, Kyla Harrison, a Manhattan eighth grader, attended math class in an unusual setting: Hamilton Fish Park.

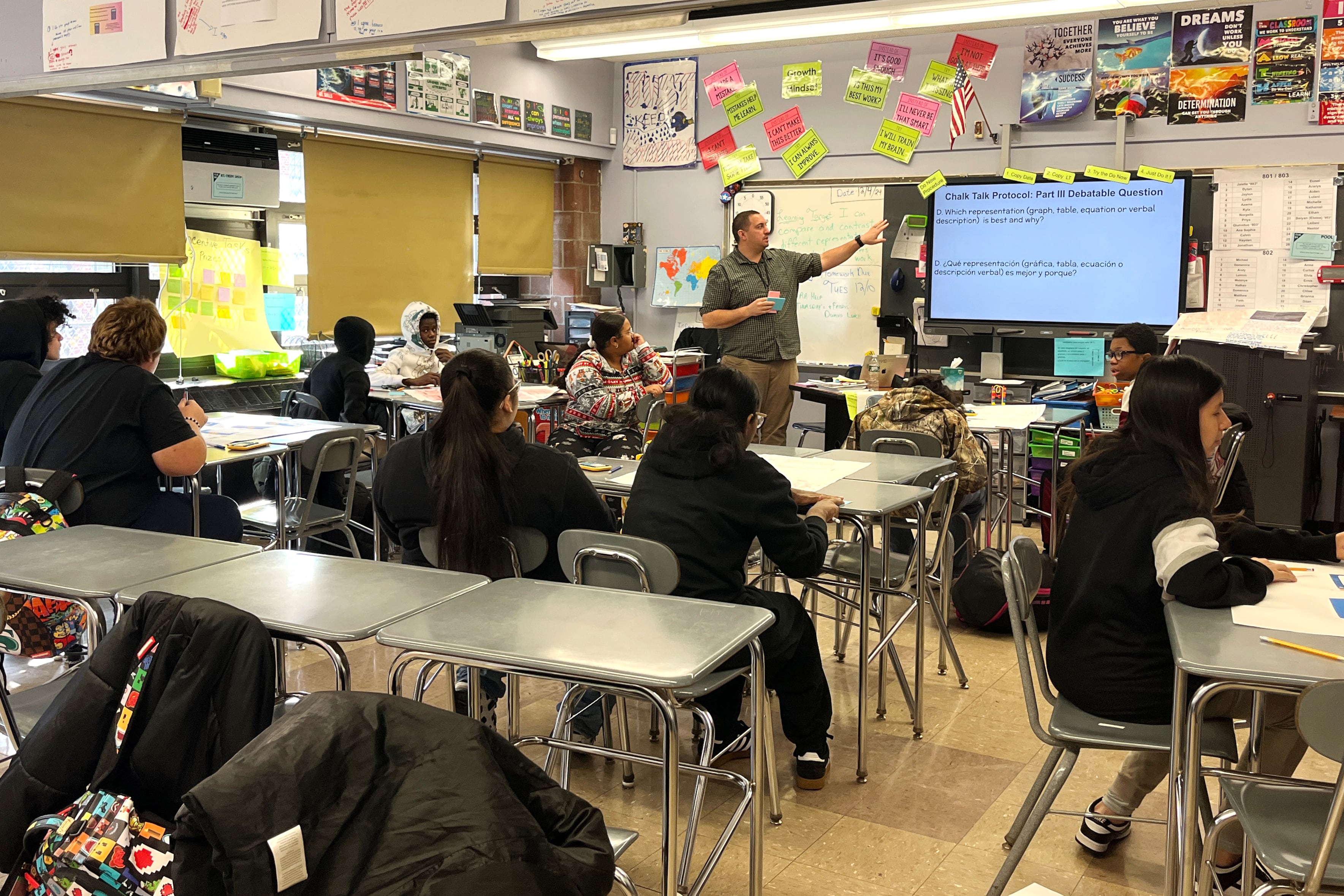

During the excursion, Kyla and her classmates calculated the slopes of staircases in the park — an activity that was a natural extension of the teaching philosophy at the School for Global Leaders, an International Baccalaureate middle school on the Lower East Side.

The International Baccalaureate program, often referred to as IB, centers student learning in self-directed, project-based work, aiming to help students take greater ownership over their academic work and establish connections between the knowledge they gain in the classroom and its real-world applications.

Some New York City schools have embraced the model as a way to offer families rigorous academic options outside of “gifted and talented” programs, which often sort and separate students within campuses. Offered across the globe, the IB program — which requires schools to undergo a multi-year accreditation process— may see increased interest among city schools seeking to distinguish themselves as the state changes diploma requirements. Regents exams are expected to be optional by fall 2027. Meanwhile, the IB program already offers state-approved alternative exams to the Regents.

For Kyla, trading worksheets for a concrete example made the lesson more memorable.

“I’m definitely going to remember how to calculate slopes,” she said. “It’s more fun when you get to interact with the work, instead of just sitting in a boring classroom all day.”

And though she’s nearing the end of her time in the middle school program, Kyla isn’t quite ready to leave the unique academic environment she’s found at the School for Global Leaders. She plans to stay at the school as part of its first ninth grade class next year, as the school looks to expand to a 6-12th grade program.

Principal Keri Ricks hopes the expansion will give local families a wider menu of academic options when considering where to attend high school. And for students like Kyla, Ricks said the high school will offer a chance to stick with the IB curriculum over a longer period, facilitating further growth.

Statewide, there are 121 accredited IB schools in New York, including about 106 public schools, according to the IB website. As of last year, at least 17 public schools across the five boroughs offered the IB curriculum, and more appear to be in the works. Brooklyn’s District 13 has added eight IB elementary schools and four IB middle schools in recent years, in part to offer families an alternative to more exclusive gifted programs. (Only four of the district’s schools were represented in the data.)

“The IB program definitely cultivates a deeper understanding of the curriculum,” Ricks said. “It’s not teaching math in a step-by-step format. It’s teaching math in the global context of how we’re going to use it in the real world.”

She pointed to a recent seventh grade outing to tourist hotspots like the Empire State Building around midtown Manhattan. Students had to devise their own visitor guides to the various locations — calculating distances between them and optimizing walkable routes, while also learning about the history behind the city locations.

The school serves about 150 students across its middle school grades. Expanding to a high school program over the next few years, the School Global Leaders hopes to welcome about 100 students per grade, Ricks added. The school already has classrooms allocated within the building for its incoming ninth graders, with sufficient space available to build out additional high school grades, Ricks said.

The school is also planning to offer a career-focused track that specializes in computer science — giving students a chance to earn skills and experience that will translate into careers in the field. Through the IB program’s partnership with Arizona State University, Ricks hopes students will be able to take virtual computer science classes at the university, potentially earning certification in different computer science programs while still in high school.

Starting up a high school program isn’t without its challenges, particularly as state education officials are engaged in a multi-year process to update New York’s high school graduation requirements. That effort seeks in part to expand options for students, introducing more project-based assessments and other means of demonstrating proficiency in core subjects.

Though that effort appears to pair well with the philosophy of the IB program, it also introduces some uncertainty, Ricks said.

“We are building it out using the state requirements,” she said. “But we are also thinking about how we need to be able to change on a dime.”

Parents, educators say IB program has bolstered student engagement

Parents and educators at the school said the creative freedom offered by the IB curriculum had allowed their students to excel.

For eighth grader Jaielle Alejandro Welch, an English unit on mystery novels let her own creativity thrive. She had the opportunity to write her own mystery story inspired by her love of Agatha Christie and other mystery writers. Then, she turned her story into a pitch for a Netflix T.V. show.

“I enjoyed it so much,” Jaielle said. “To learn about different kinds of writing techniques, and to compare perspectives, and to learn about how people might react.”

Jaielle’s mother, Jenay Alejandro, attributes her daughter’s recent academic strides to her heightened engagement with her work.

“She talks about it all the time,” she said of the mystery story assignment. “We’ve been beyond happy with her growth. I don’t believe in the test, the test, the test, but all her scores have just skyrocketed over the past couple years.”

As part of his class, Anthony Sanchez, a Spanish teacher at the school, tasks his students with completing “neighborhood reviews.” Students are encouraged to spend time in Latino communities in New York City with their families, using their Spanish skills to order food from restaurants, and listening to everyday conversations in the neighborhoods.

“That’s what really differentiates IB,” he said. “You’re not trying to just fill in a check box, you’re trying to equip this human being with tools to traverse the world.”

And as the school expands to serve high school students in the coming years, Ricks said she hopes to attract individuals who are eager to shape their own academic experience.

“I think the beauty of it is that we’re at a place right now where we’re building the program,” she said. “That’ll give us amazing opportunities to actually sit with the kids that are going into this program and figure out: What are their interests? What are their wants? What do they want to study?”

Julian Shen-Berro is a reporter covering New York City. Contact him at jshen-berro@chalkbeat.org.