Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

When her daughter was suspended last spring for having vape pens, including one with marijuana, Brooklyn mom Rubi F. thought the family had a good reason to fight the case: She claimed a classmate slipped them into her bag.

At a hearing to determine if the allegation was true, the school didn’t present concrete evidence about the pens’ contents, according to a legal filing. But the hearing officer still sided with the school, finding the eighth grader had “liquid THC in a vape pen” and was “in possession of drug paraphernalia.”

“They just go by what [the school staff] said,” Rubi said in Spanish through an interpreter. “It’s very unfair.” (Rubi asked that her last name be withheld to protect her family’s privacy.)

A lawsuit filed this week on behalf of Rubi and two other families contends that New York City schools often suspend students without solid evidence, in violation of their due process rights under the U.S. Constitution. The lawsuit could have significant implications for thousands of students every year. If the suit is successful, it would become harder for schools to remove children from class for long stretches.

“All the school has to do is show some piece of evidence that makes the hearing officer feel like this could have happened,” said Michaela Shuchman, a lawyer at Legal Services NYC, an organization that represents families in suspension proceedings and which filed the lawsuit. “It really demoralizes [families].”

When children are removed from school for six days or more, known as a superintendent suspension, families are entitled to a hearing where they can present evidence, call witnesses, and challenge the school’s version of events. A hearing officer determines which facts are true and makes a discipline recommendation.

But the standard of proof at those hearings — “substantial and competent evidence” — requires less than a 50% chance that a student did what they are accused of, legal experts said.

The suit, filed in federal district court, argues that the city should use a standard known as “preponderance of the evidence,” which would require slightly more than 50% certainty. At least 19 states use the preponderance standard, according to Shuchman, including New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut.

Lengthy suspensions can seriously deprive students, suit claims

Some school staff have noted that longer punishments are typically reserved for serious misconduct and making it harder to remove students can lead to more chaotic classrooms. But the lawsuit’s backers contend that a higher burden of proof is appropriate given evolving research on the impact of lengthy suspensions.

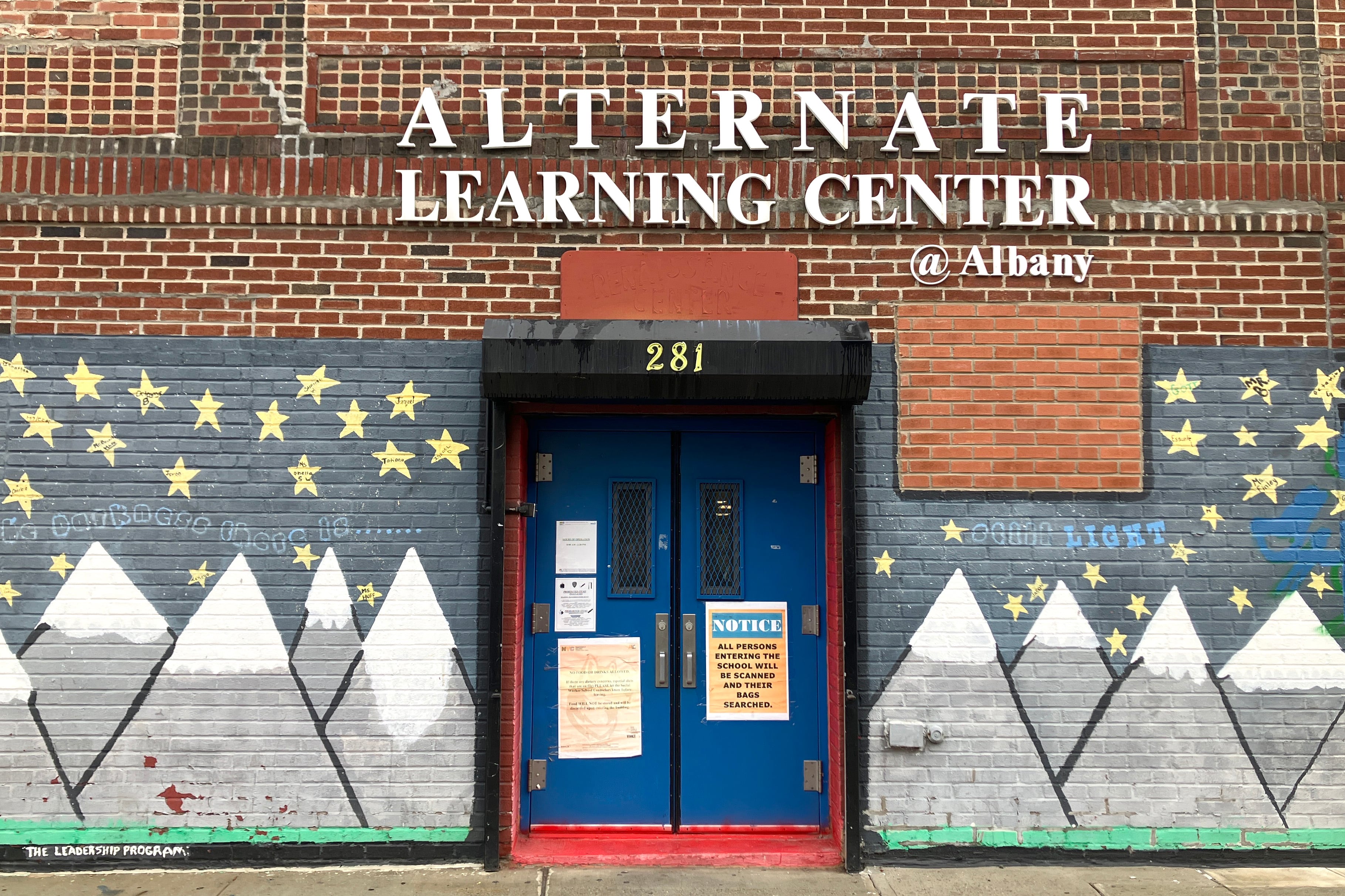

One study focused on New York City found that suspensions can lead students to pass fewer classes, increase their risk of dropping out, and make it less likely they will graduate. Other research generally shows suspensions are linked to worse academic outcomes. Though students who are removed from class are entitled to instruction at alternate learning centers, attendance is often spotty and teaching can be disconnected from what students were previously learning at their home school.

The punishments can also contribute to students getting entangled in the criminal justice system and limit access to free meals and health care, as schools have increasingly become hubs of social services, the suit claims.

Rubi’s daughter, who has a disability, did not receive all of her special education counseling services when she was assigned to an alternate learning center. She was sometimes sent home with worksheets immediately after arriving, according to the suit.

“The impact was so huge on her” after the suspension, Rubi said. “She was a totally different person. She became very angry all the time.” The mom now has to drive her daughter to school because she will otherwise refuse to go.

The principal of I.S. 96 Seth Low, the school that suspended Rubi’s daughter, did not reply to an email seeking comment. (Schools are allowed to discipline students for merely possessing a vape, although they should not typically be suspended unless drugs are involved, according to the city’s discipline code.)

The impact of lengthy suspensions is unevenly distributed. Nearly 45% of the 6,231 long-term suspensions last year involved Black students, and a similar proportion were issued to students with disabilities. Only about 20% of the city’s students are Black, while just 22% have a disability.

Chalkbeat reported this week that the city has failed for years to follow rules designed to protect students with disabilities from long-term punishments if the behavior in question is related to their disability.

An Education Department spokesperson referred questions about the lawsuit to the city’s Law Department, which declined to comment.

Advocates who represent students in suspension hearings have long raised concerns about the standard of proof used in those proceedings. In a 2019 Chalkbeat essay, one advocate cited a case where his client was suspended for punching another student. The suspension was upheld based on an account from a school dean — even though the student who was hit testified that someone else was responsible.

Multiple legal experts said the serious consequences of long-term suspensions merit a higher standard of proof.

Under the current standard, “they’re giving a lot of deference” to schools, said Cara McClellan, an associate practice professor of law at the University of Pennsylvania. Using the preponderance standard would be “a step toward making it a fair and equal adversarial process,” she said.

Other legal experts said the lawsuit may be a longshot. Under current U.S. Supreme Court precedent, students have a right to notice of a suspension and a hearing, but the court did not articulate a specific standard of proof.

Using the higher preponderance standard is a “commonsense argument,” said David Bloomfield, a professor of education, law, and public policy at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center. But he said that might not be enough to convince a judge that the current standard is unconstitutional.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.