Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

With just six weeks to go before all New York schools must comply with a “bell-to-bell” ban on cellphones, officials said they are putting $29 million behind the effort for New York City’s public schools.

But the funding — $25 million from the city and $4 million from the state — has not yet been distributed to schools, and officials did not say when it would become available.

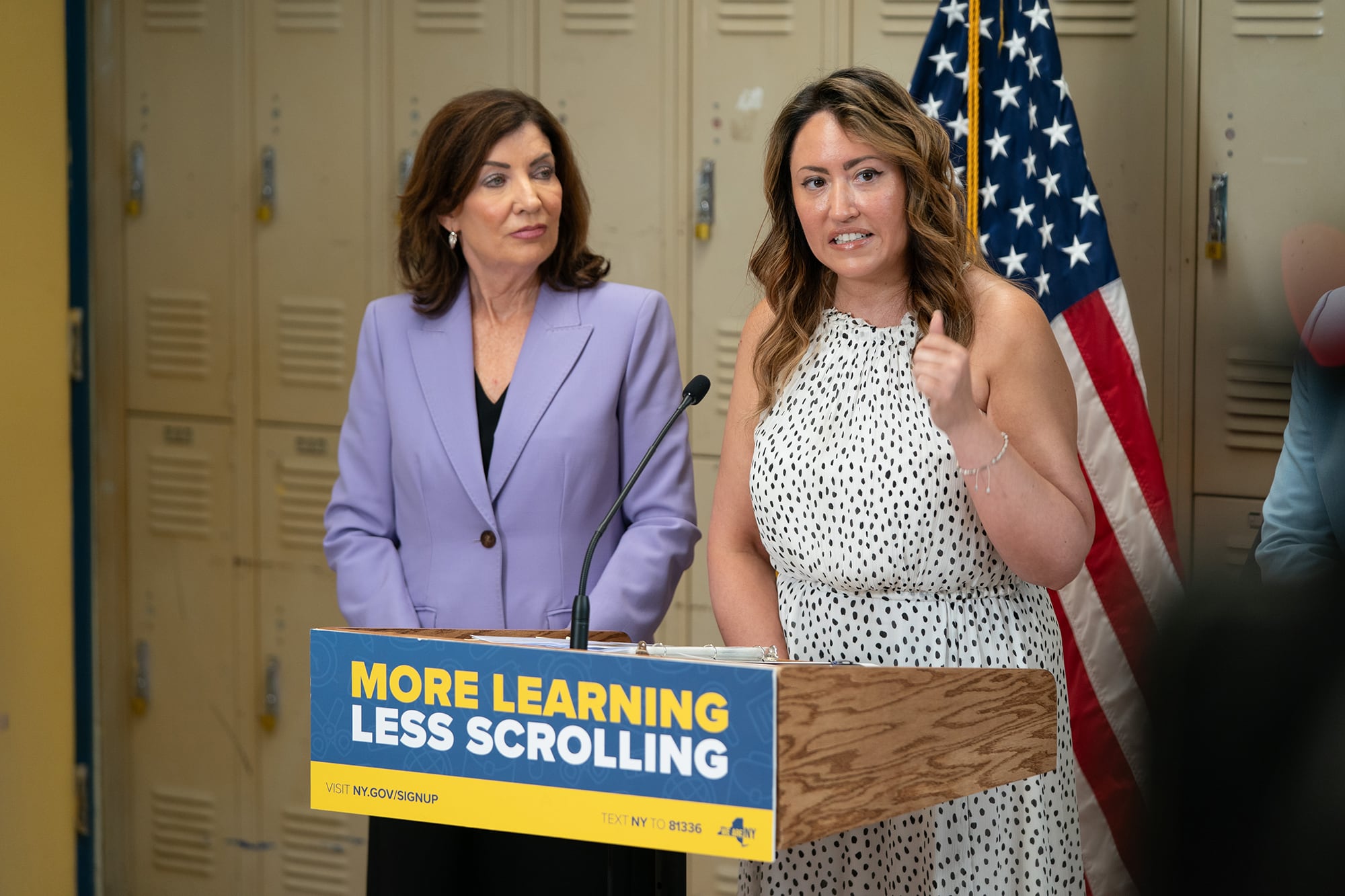

Many school leaders have been planning to implement cellphone bans for months, and more than half of the city’s schools already restrict cellphone use, Chancellor Melissa Aviles-Ramos said Wednesday at a Bronx press conference with the governor. On many campuses, students use lockable pouches or store their phones in bins or lockers before they head to class.

But other principals may still be devising their policies, decisions that could be complicated by the uncertainty about the availability of funding.

A city Education Department spokesperson did not respond to questions about when funding would be distributed. Officials said some schools that recently purchased storage devices could be eligible for reimbursement.

The $29 million earmarked for New York City represents roughly $35 per student in grades K-12, which is about the cost of Yondr pouches, cloth devices with metal locks that students keep with them during the day. The state’s contribution, which is designated for secondary students only, will be made available to districts on Aug. 29.

During a joint appearance with Aviles-Ramos on Wednesday, Gov. Kathy Hochul stressed that the policy is meant to reduce distractions, boost learning, and improve students’ mental health.

It may be a difficult transition for students, she acknowledged. “We have to prepare the parents for really what will be a detoxing period for them,” Hochul said.

In New York City, Aviles-Ramos said principals must be ready to restrict phones on the first day of school and will not be granted leeway to slowly phase in the new policy.

“If we slowly trickle it into the school year, what ends up happening is we miss the moment,” Aviles-Ramos said. “Habits are built from day one and so we are going to be ready on day one.”

New York City officials have already updated the Education Department’s guidance, which had been on the books for nearly a decade, after former Mayor Bill de Blasio lifted the school system’s cellphone ban over equity concerns. (He worried that students at schools with metal detectors were hit harder by the ban, forcing many kids at low-income schools to pay $1 a day or more to store their phones at bodegas.)

The new guidelines call on schools to come up with a plan to store all internet-enabled devices — cellphones, smartwatches, laptops, tablets, MP3 players, and game consoles — that students bring to school. Possible methods include: school storage lockers, students’ assigned lockers, or Yondr pouches. Schools are also on the hook for providing a way for students to access their stored devices during school hours “when necessary.”

“The law is very flexible, and it does not state that we must collect, and so there are a number of methods that schools can use,” Aviles Ramos said.

Officials outlined a host of exceptions, such as for specific education purposes, to monitor medical conditions, or for student caregivers. Devices might still be used for translation services, for student emergencies, or for reasons related to a student’s special education plan. (And students can have access to their devices if they go off campus for lunch, which adds another logistical complication for schools.)

Schools must also provide families with their direct phone number or any other ways they can contact their children in an emergency during the school day. Schools must clearly explain how students will be disciplined for cellphone ban violations as well policies for confiscating devices when students violate the rules. Students may not be suspended solely because they violated their school’s cellphone ban and accessed a device during the school day, the city’s guidance states.

The city also requires schools to consult their school leadership teams, which include principals,teachers, and parents, on developing their cellphone policies. These teams, however, don’t typically meet during the summer.

The rules are expected to be voted on by the Panel for Educational Policy on July 23.

This story has been updated with an additional response from the city Education Department.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex atazimmerman@chalkbeat.org.

Amy Zimmer is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat New York. Contact Amy atazimmer@chalkbeat.org.