Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

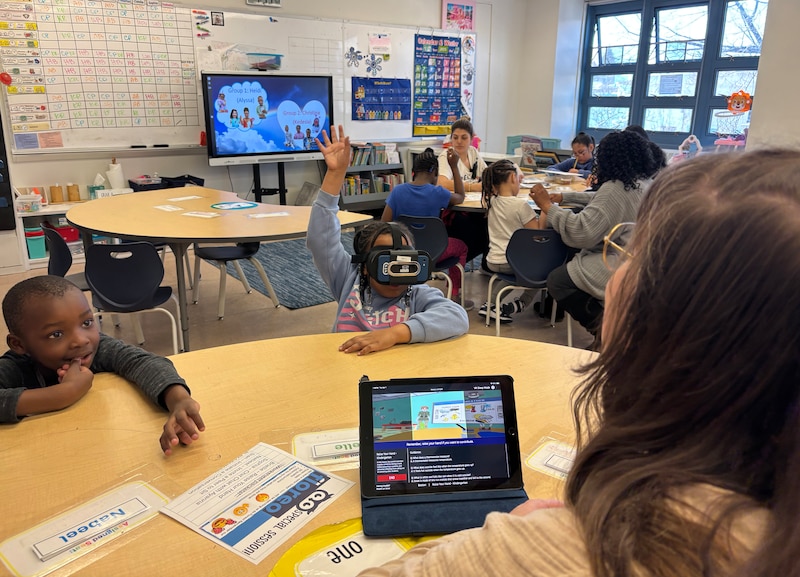

In a sunny classroom at the New York City Autism Charter School in the South Bronx, young children eagerly waited their turn to step into a cartoon virtual world.

A girl in a lavender and pink Disney sweatshirt strapped on the virtual reality headset, resembling futuristic ski goggles. Through the VR program, she will be learning to raise her hand and take turns.

Heidi Brueckmann, her teacher and a clinical supervisor at the school, sat opposite the student and views and operates the virtual reality program, called Floreo, through a tablet. Her screen displayed what the child saw, along with prompts to help her coach the student through the lesson.

Virtual reality, increasingly, is becoming an educational tool for autistic people. The tech is backed by research suggesting that virtual reality can help children and adolescents with autism. A review study published in May in the Journal of Internet Medical Research analyzed 14 previous studies on VR’s role in autism therapy and found multiple benefits, especially with social skills such as understanding social cues, interpreting facial expressions, engaging in conversation, and forming or maintaining relationships.

The student’s goggles placed her inside a colorful VR classroom populated by a virtual teacher and animated classmates. A virtual whiteboard displayed weather-related drawings and words. Brueckmann prompted the virtual teacher to ask questions. When the virtual teacher asked what a thermometer measures, Brueckmann’s student called out the answer. Brueckmann tapped a button, prompting the virtual teacher to remind the girl to raise her hand. Then, with the press of another button, Brueckmann prompted the virtual teacher to ask the question again.

One of the benefits of the VR setup, Brueckman said, is that it enables her to work individually with a student while teaching them to interact with other kids. In real-world group settings, it can be hard to coach kids through scenarios when they are surrounded by, and potentially interacting with, other students who are struggling with similar social skills.

“If I have two kiddos who both have some deficits in their social skills,” Brueckmann said, “it can get a little muddy.”

Benefits of virtual reality as a teaching tool

In the past, VR equipment was heavy, expensive, uncomfortable, tethered to a computer, and located in research and academic environments. Now, lighter-weight, moderately priced, stand-alone virtual reality goggles have made the tech much more accessible in various settings. Medical schools use VR to train surgeons. VR is also used to train emergency responders and to distract patients with chronic pain. A growing number of educators, like those at the New York City Autism Charter School, are embracing the technology to help their neurodiverse students.

Virtual reality scenarios can help autistic people build confidence as they practice real-world tasks. For example, crossing-the-street simulations teach safety awareness and decision-making in traffic, while virtual shopping environments offer opportunities to practice making purchases, handling money, and interacting with cashiers. Other scenarios focus on navigating public transportation, helping users learn to read signs, board buses or trains, and ask for assistance when needed — all in a controlled, low-stress setting.

Before virtual reality emerged, teaching social skills involved things like watching videos about how to start a conversation, said Maggie Mosher, an assistant research professor at the University of Kansas who studies artificial intelligence and extended reality in education.

Watching videos is usually too passive to help children get it, and “direct instruction feels so monotonous,” she added. And a commonly used teaching method, applied behavior analysis, also known as ABA, has come under fire in recent years for pushing children with autism to drop behaviors they find soothing, such as flapping or stimming, no matter the emotional cost.

Virtual reality, by contrast, is immersive and immediate, and it’s fun, like a video game, Brueckmann said. Her students look forward to their turn.

“We use it as reinforcement for completing work,” she said. The students remember and request specific virtual reality activities. When they finish other tasks, they might get to explore an ocean simulation or observe a virtual pride of lions — activities that spark curiosity and engagement.

And VR encounters are low-stakes because the other people involved aren’t real. No one is going to get teased or end up feeling embarrassed.

“They don’t feel afraid to ask questions, to tell you things that they maybe wouldn’t say out loud if they didn’t know the answer,” Mosher said. “And you really know how they would react to certain situations.”

Designing VR teaching modules with, and for, neurodiverse learners

Floreo, the VR program used at New York City Autism Charter School, teaches skills such as crossing streets safely, recognizing bullying, and even how to go trick-or-treating. Its creator, Vijay Ravindran, got the idea after watching his autistic son engage with early examples of virtual reality-type technology.

“One day, after spending some time exploring a dinosaur simulation and Google Street View in virtual reality, my son began acting out what he had just seen,” Ravindran said in an email. “For many autistic youth, pretend play and social skill development don’t come easily—but in that moment, I saw VR spark something powerful.”

More than 100 schools and therapy offices in the U.S. currently use Floreo, which is one of a handful of virtual reality-based programs with autism-related applications. Others include SocialWiseVR, a program that helps adolescents navigate attending parties and workplace situations, such as accepting feedback. Another program, Blue Room, focuses on helping children manage phobias.

Some creators of VR apps for autistic people recognize the risk of repeating the coercive teaching methods of ABA that characterized previous teaching tools for autism. To avoid this, Nigel Newbutt, an assistant professor of advanced learning technologies at the University of Florida, includes autistic co-researchers in his work.

“I don’t like the idea of using this technology to fix autistic people and make them conform to neurotypical norms,” he said.

Instead, he believes virtual reality should be designed through a “disability lens, where environments are being created more inclusively, to adapt to and receive and enable autistic people.”

Newbutt’s team worked with an autistic young man to develop a VR program about the social norms of eating out in a restaurant. His input shaped the storyboard, interactions, and key steps — insights the team wouldn’t have had without his involvement.

However, widespread implementation of these VR tools remains a challenge, says Noah Glaser, assistant professor at the University of Missouri’s School of Information Science & Learning Technologies. The cost of the equipment can be a barrier, as well as varying levels of comfort with technology among families and teachers. Many insurers do not cover virtual reality therapies — a headset can cost hundreds of dollars. And using these tools effectively requires some technical support to get up and running, says Glaser.

Some schools have overcome these obstacles through partnerships and government funding. At the New York City Autism Charter School, where most of the 34 children are from low-income households, Floreo is paid for with a grant from the Disability Opportunity Fund, and the company provided the technical expertise and training needed for a smooth rollout at no cost. And the platform qualifies for reimbursement under Medicaid waiver programs in six states, including New York. Floreo is also approved for reimbursement through the New York State Office for People With Developmental Disabilities as assistive software.

When the young student in the Bronx finished her weather lesson, she passed the goggles to one of her classmates, in a lemon-colored party dress, who entered a world designed to teach turn-taking in conversation. The program is called “Chit Chat with Ayanna” and featured a friendly-looking virtual child in a wheelchair who sits in a park waiting to be greeted.

Next up for the VR tool was a little boy with short-cropped hair in a long-sleeved black and grey shirt, who was practicing making friends and asking them to sit with him in a classroom. In this simulation, a virtual boy walked in the door, and the prompt was “try waving him over.”

Brueckmann has seen her students make real-life progress using virtual reality. One child who initially avoided her peers began sitting closer to them after practicing social scenarios in VR.

“Even if she still prefers her own table,” Brueckmann noted, “she’s now waving to other kids from across the room.”

This story was produced in partnership with Healthbeat and the Health & Science Reporting Program at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY.