Sign up for Chalkbeat Philadelphia’s free newsletter to keep up with news about the city’s public school system.

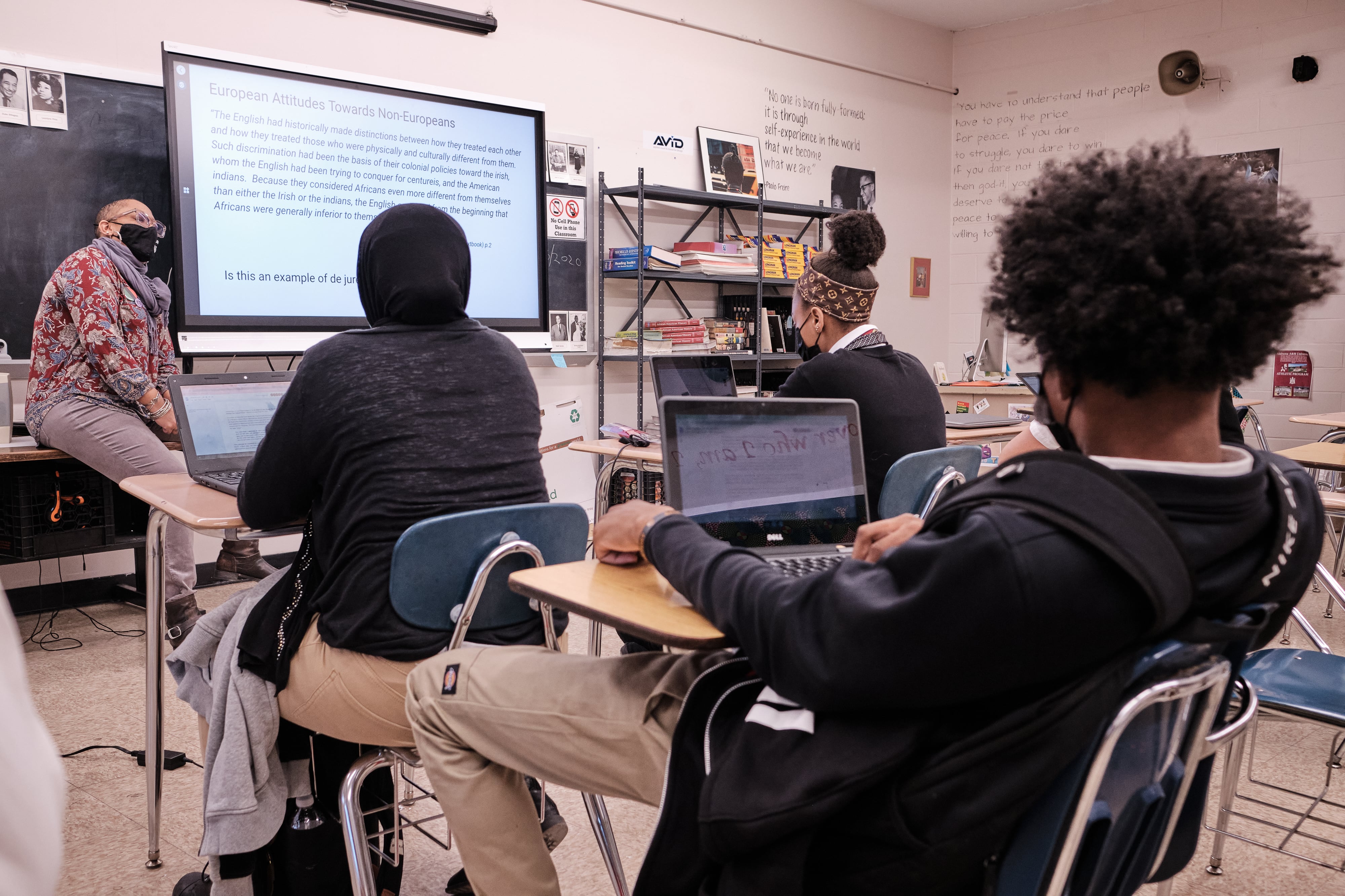

In 2005, Philadelphia became the first big city in America to require all students to take African American history in order to graduate. And as other states and districts pass laws and adopt policies that restrict teaching about race and racism, the city’s public schools are taking a very different approach to classroom topics now under a national microscope.

The district is redoubling its efforts to expose students to Black history and culture. This year, it debuted a substantially updated and revitalized curriculum for the course of study that relies mostly on primary and secondary sources rather than a standard textbook.

Students examine such essential questions as how Black communities retained their cultural identity in colonial America, and they compare the philosophies that motivated figures like Booker T. Washington and Marcus Garvey.

They also discuss whether the nation’s founders were “hypocritical for claiming freedom” while they tolerated slavery in the nation they were creating. And they are asked to ponder why the history of slavery should be taught in schools to begin with.

Philadelphia’s revisions to the course and new training for teachers track with the Board of Education’s commitment in 2021 to “address racist practices” in a multitude of areas, from discipline to the content of classroom libraries. Part of the board’s goal is to ensure that the district’s students, most of whom are Black or Latino, “see themselves in the curriculum” throughout their school careers.

The district is also incorporating instructional materials about Black history beyond the high school course. And the new materials can look quite different from things like traditional classroom textbooks.

Philadelphia’s updated high school course creates a natural avenue for students to think about and discuss topics and authors that were recently removed from early drafts of the Advanced Placement African American Studies course that the College Board has been piloting.

The controversial elimination of topics like the Black Lives Matter movement and Black feminism took place following prominent complaints from Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican. The College Board has said that it did make changes to the course, but not due to political pressure.

Ismael Jimenez, the district’s social studies curriculum specialist and a driving force behind the revisions, cited the growing number of states where, as he put it, “You can’t even have these conversations” like the ones he wants to encourage.

Since early 2021, 18 states have enacted bans or restrictions on teaching topics related to race and racism, according to Education Week.

Legislators in Pennsylvania did make an effort in 2021 to restrict what could be taught about race, but their bill about the topic has failed to gain traction.

In Jimenez’s view, educators now have an even bigger obligation “to teach children the truth.”

New reading material and new training

Teachers in Philadelphia still have a Prentice-Hall textbook from 2005 for the mandatory high school course. But Jimenez said although the textbook is advanced considering when it was published, the district has also incorporated more primary sources, like Marcus Garvey’s “The Negro World.” The course relies on digital access for books like Garvey’s, which is available through the New York Public Library.

Links to sources, topics to be covered, and pacing schedules are listed for teachers in shared Google documents, which are continually updated.

When he taught the course for more than 12 years at two different high schools, “I found myself making my own materials,” Jimenez said.

Schools are also using materials that aren’t just more recent than Garvey’s work, but present history in a different way.

Earlier this month, Jimenez spoke to Philadelphia teachers and other district employees — many of whom work in elementary schools or preschools and don’t teach the mandatory high school course — at a Temple University event unveiling a new book for use in city schools called “Black Lives Always Mattered!”

The book was written and illustrated in the style of a graphic novel. It features 14 Black figures from 20th century Philadelphia history. These range from luminaries like opera singer Marian Anderson and sociologist W.E.B. DuBois, to lesser-known people like teacher and political activist Crystal Bird Fauset, photojournalist John W. Mosley, and Ruth Wright Hayre, who in the 1940s became the first Black high school teacher in the district and later rose to be Board of Education president.

The book’s lead illustrator and art coordinator is Eric Battle, who has worked for Marvel Comics and other publications. Battle said work on the book began in 2018, well before controversies about lessons on race and racism that are now making headlines.

“It came about as a way to let young people know their connections to the city, knowing why a street is named after a certain person. What did that person do to garner such an honor?” Battle said. “We want them to know that the people profiled in this book are ordinary people who did extraordinary things.”

Other changes are afoot to bolster the revised course.

While the student body in Philadelphia is mostly Black and Latino, more than two-thirds of the teachers are white. And although the mandatory course has been in city schools for 17 years, this is the first year teachers are required to attend professional development focused on the class.

Jimenez, who fought hard for the mandatory training, said it can be “problematic” if teachers “are left on their own without appropriate guidance” before presenting such important and potentially sensitive material.

Unlike in science, where teachers in Pennsylvania must be certified in the specialties of biology, physics and chemistry, social studies teachers have no such restrictions. They can be assigned to teach any required course, regardless of their expertise, even though “you have to be very knowledgeable on the subject before being able to go in and determine what should be emphasized or not,” Jimenez said.

Nicholaus Bernadini, who works at Samuel Fels High School, has been teaching African American history for 14 years and worked with Jimenez alongside other teachers to revise the mandatory high school course.

Bernadini, who is white and was born in Philadelphia, spent most of his formative years in Sea Islands, South Carolina among the Gullah people, a group of Black Americans who live along the southeastern coast and developed a distinctive culture. That background gives him a unique perspective. But Bernadini also recognizes that teachers from all walks of life can face “pitfalls” when dealing with the material.

“Teachers navigate better in environments where they can ask questions on what they are unsure about,” Bernadini said. “It is important for teachers to feel free to improve themselves as educators without backlash.”

During the professional development sessions for teachers on the course, Bernadini said there have been “incredible” conversations about everything from the role of states’ rights in the Civil War to personal perspectives on race.

“We had an educator talk about the idea that they don’t necessarily see color. We had a discussion around that along the lines of, ‘We can respect that, but what’s the impact of that mindset on you and your students?’” Bernadini said. “And while not all white teachers think that, there are teachers of color who don’t necessarily disagree. So having these conversations gets teachers to feel more comfortable about teaching the content.”

Jimenez said that teachers have told him that they appreciated the professional development sessions on a personal level.

“They realize that a lot of things they emphasized before were problematic and that it’s a reflection of the indoctrination in what society tells us about racial progress,” he said.

Teachers see broad benefits of learning Black history

Teachers at different levels of the school system say how invaluable it is for students to encounter things in their classes that presents them a fuller picture of American history through the lives of Black people. And they’re puzzled if not angered by those who say otherwise.

Tiffany Johnson teaches fourth grade at Ziegler Elementary School. Her students are learning about topics ranging from Black women’s contributions to society to the Green Book, a 20th century guide for Black travelers to the places they would be welcome to stay and to have a meal, where they could get their hair done, and which gas stations to patronize.

Many of her students previously had no idea about the existence of things like the Green Book in American history, she said.

“I don’t see what’s wrong with teaching the truth of what happened. I don’t get that. It’s not like we’re saying white people are bad,” said Johnson, who is Black. “We’re saying these events happened, this is how people reacted. The facts need to be told. It happened. We can’t sugarcoat it.”

Monique McKenney, now at Central High School, has taught African American history for most of her 24 years in Philadelphia schools. She said she is “not shocked, but disappointed and outraged” that politicians like DeSantis “would try to water down, or whitewash a curriculum that all students would benefit from.”

Central, one of the city’s leading academic magnet schools, is racially and ethnically diverse but it is predominantly white and Asian, unlike the district as a whole. In McKenney’s experiences, a broad cross-section of students have benefited from the lessons she teaches about the topic.

“It’s interesting to see students of various backgrounds who are able to connect with some of the experiences that you have in African American history,” said McKenney, who is also Black.

Some students, she said, “are surprised they’ve never heard about certain things before.”

Dale Mezzacappa is a senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia, where she covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in Philadelphia. Contact Dale at dmezzacappa@chalkbeat.org.