Sign up for Chalkbeat Philadelphia’s free newsletter to keep up with news on the city’s public school system.

Martin Luther King High School social studies teacher Nadirah O’Connor said her students have a lot of questions.

They want to know why their neighborhood is impoverished. Why so many guns are on the street. Why “every five minutes” they are going to a funeral.

And why in nearby wealthier and whiter neighborhoods like Chestnut Hill, there seems to be none of that.

There are no easy answers, but O’Connor tries to unpack these issues in her civics classes, where students learn about the roles of local, state, and federal governments and the responsibility of citizenship.

In time for the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence next year, both the Commonwealth and the school district are taking steps to make sure students graduate high school understanding how the government works and the responsibilities of active citizenship.

The state has embarked on a bipartisan effort to provide guidelines and standards for civics instruction, which is now left up to individual districts. At the same time, Philadelphia is completing a major revision of its civics curriculum, which is required for graduation.

“We don’t even have an explicit civics content course until senior year,” said Ismael Jimenez, the district’s director of social studies. “And it has not been updated in two decades.”

Nyshawana Francis-Thompson, the district’s chief of curriculum and instruction, said the goal is to help students “think critically and act responsibly” when it comes to public affairs and to inspire them to participate in civic life.

On the state level, two former members of Congress, Democrat Joe Hoeffel of Philadelphia and Republican Jim Gerlach who represented parts of Chester and Berks counties, have formed a coalition of educators and good-government groups to focus on the quality of civics instruction across the Commonwealth.

The coalition is now working with districts and educators to offer guidelines and resources for curriculum development and “elevate the importance of this subject statewide,” according to Justin Villere, director of civic education for the Committee of Seventy, the good government group that serves as the fiscal agent of the coalition.

The state and district initiatives are independent of each other, but both come as the Trump administration is attempting to ban anything that could be construed as DEI — diversity, equity and inclusion — and the nation’s political polarization is heightening tensions about politics in the classroom.

Beyond the DEI ban, the Trump administration is also actively seeking to redirect civics instruction away from what it has termed “woke priorities” such as the rights of immigrant and transgender Americans to “the principles of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.”

Not lost on either the city or state officials is that in one of the most important swing states in the nation, students can graduate high school without instruction on how the government works and the importance of voting. In Philadelphia and Pennsylvania, just over half of 18-year-olds were registered to vote, at just under 54% in 2024. By comparison, nearly 74% of the voting-age population as a whole was registered to vote in 2024. Laura Brill, founder of the nonprofit voting advocacy group The Civics Center, cautioned that 18-year-olds are less likely to register in years in which there is not a presidential election.

Pennsylvania civics instruction lacks ‘teeth’

Pennsylvania students have been required to pass a civics test in order to graduate since the General Assembly passed Act 35 in 2018. But, bowing to local control, the state has never specified what the test should include or even whether districts must offer a civics course.

As a result, civics instruction varies widely; Gerlach said a goal of the coalition is to set guidelines, provide more resources for teachers, and develop more programming.

“There’s just not a lot of teeth to [Act 35],” said Villere. Beyond having to send reports to the Pennsylvania Department of Education on what percentage of their students passed the test, the law “doesn’t say what it is assessing, what students need to do to pass, or what are the goals” of civics instruction, he said.

The website, PACivics.org, offers a limited toolkit for teachers, a 2021 report by the conservative-leaning Fordham Institute ranked Pennsylvania near the bottom among states in civics instruction, giving it an F “for the quality, rigor and organization of civics and US history standards.”

Still, little attention was paid until now. “This is a really important conversation,” Gov. Josh Shapiro said when Hoeffel and Gerlach announced formation of the coalition. “The central thing is to focus on teaching our students more about civics and more about how to be discerning about what they read and what they take in on social media.”

That’s part of what Philadelphia’s curriculum update aims to do — although some City Council members, teachers, and civic groups, including Villere’s Committee of Seventy, were disappointed that the Board of Education passed a fiscal 2026 budget that failed to include full funding to pay teachers for continuing to work on the revision or to maintain a “voter champions” program that pays a staffers in high each schools to promote student voter registration.

“District teachers are developing locally relevant, high-quality civics instruction at a fraction of typical costs, yet this funding keeps getting interrupted,” they said in a June letter to Superintendent Tony Watlington and school board members.

“I don’t see this board not supporting civics education,” said board President Reginald Streater in an interview. He noted there was “a lot going on” at the time the budget was voted on, including consideration of charter nonrenewals and dealing with a federal investigation of the district’s handling of asbestos removal in schools. The funds for the civics rewrite and the student registration effort was a tiny piece of the $4.6 billion budget.

Streater cited a 2019 board resolution supporting robust civics instruction and declaring a “student voter registration day” every September. He said, if necessary, it might be possible to find another revenue source to make sure the civics work is completed.

“This board supports the holistic education of students and cares deeply about student civic engagement,” he said.

‘We don’t have to cower from teaching the truth’

Historically — and not just in Philadelphia — complaints that teachers used civics classes to promote a political agenda has tamped down educators’ focus on the subject, a fear that has come to fruition under Trump.

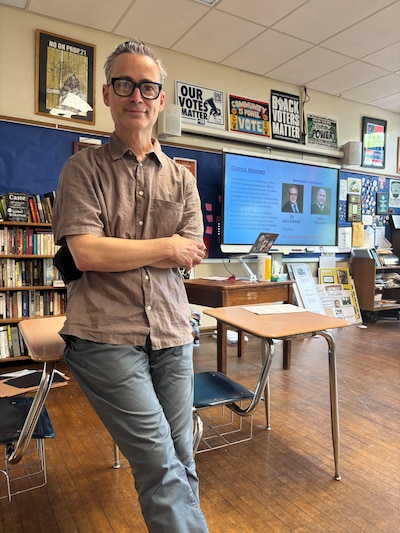

“I think that teachers do have to be careful not to play into that idea that we’re indoctrinating students, because we’re not,” said Central High School social studies teacher Tom Quinn, who also has been involved in the curriculum rewrite. “We’re teaching students how to understand the whole field of government and politics.

“But,” he acknowledges, “there’s lots of controversy in that.”

When Quinn founded the voter registration effort PA Youth Vote in 2018, the state Republican chair accused him of student indoctrination.

“We can’t let fear dictate what we do and don’t teach,” Quinn said. “Of course we have to be nonpartisan, but we don’t have to cower from teaching the truth if it’s what’s happening in the world.”

Plus, he said, students need guidance on how to “navigate going into adulthood as a person of color, a LGBTQ person, as a white person,” adding: “Understanding privilege and oppression doesn’t mean you have to be saddled with guilt.”

Even at Central, one of the most selective schools in the city, some students come into ninth grade not knowledgeable about the three branches of government, Quinn said. But beyond making sure they understand the balance of powers, civics education is about helping students learn how to use government — state, local, and federal — to benefit their lives, he said.

“We’re working on getting away from textbook-type instruction and more towards using authentic materials,” Quinn said. “We want to teach them how to do government.”

Many textbooks say virtually nothing about the state and local level, Quinn said, though they have a bigger impact on students’ day-to-day lives through such policies as education funding and age minimums for driving, for instance.

“Especially for students who come from disempowered, under-resourced communities, it is our responsibility to give them tools to advocate for themselves and give them political efficacy,” Quinn said. “It’s a huge responsibility, and teaching civics out of a textbook is not doing it justice.”

Kamera Osborne, a Central senior, said Quinn’s civics course opened her eyes.

“As a Black American, I want to be educated on what my people are going through,” she said.

While Philadelphia’s required African American history course is valuable, “it was my civics class that gave me the understanding of why things are the way they are,” Osborne said.

For instance, explaining the difference between de jure — by law — and de facto — by circumstance — helped her understand how personal decisions of where to live have resulted in school segregation in states like Pennsylvania today that rivals conditions in the South prior to 1954. That’s when the U.S Supreme Court outlawed de jure segregation in the Brown vs. Board of Education decision.

For his students, the big issues are “gun violence, mental health, school funding, drugs and addiction,” Quinn said. Students use a “research or inquiry process” to explore those topics and policies to address them.

In a recent class, he said, some students researched approaches to reducing gun violence, such as registries, red flag laws, and legislation aimed at straw purchasing. They studied the role of federal agencies including the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, and which Congressional committees deal with gun issues.

Often they send letters to officials and news organizations on such topics as the murder in 2022 of a Saul High School student, the effect of housing vouchers on families’ ability to maintain their homes, and legislation that would curtail the rights of transgender people.

O’Connor, the social studies teacher at King, said that when students get to her class, “they might know the U.S. is a democracy, but they are missing things. Like, where did those ideas come from? They know they are supposed to vote, but they don’t all believe that voting is important.”

While Quinn and O’Connor are concerned that attention to civics education could run afoul of the Trump administration, they say the administration’s anti-DEI agenda makes it even more important for them to make sure that students understand how government works and are well-versed in their legal rights and responsibilities.

What she wants students to understand, O’Connor said, is: “If I don’t activate my voice, nothing gets done.”

This story has been updated with a comment from Laura Brill of The Civics Center.

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated which county Republican Jim Gerlach represents.

Dale Mezzacappa is a former senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia and also reported on K-12 schools and early childhood education for The Philadelphia Inquirer and the Philadelphia Public School Notebook.