Sign up for Chalkbeat Philadelphia’s free newsletter to keep up with news on the city’s public school system.

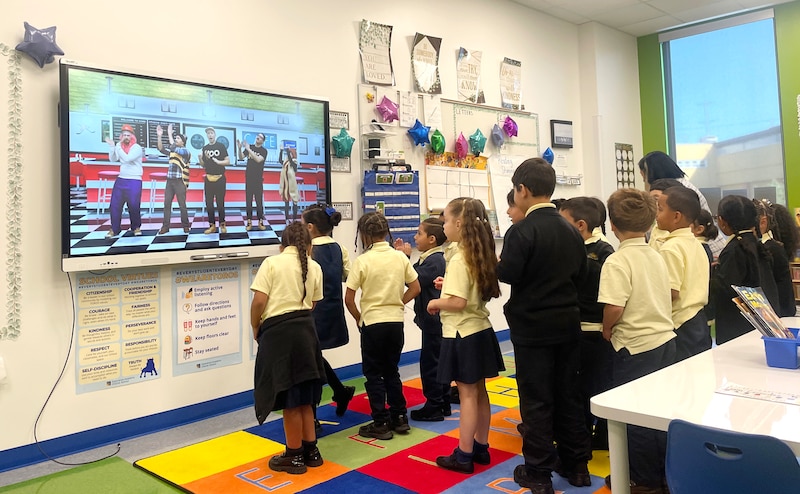

Colorful star-shaped balloons hung on a kindergarten classroom’s walls at Philadelphia’s Esperanza Academy Charter School on a recent September morning. They marked something special.

“What are the stars for?” Esperanza Academy CEO Evelyn Nuñez asked the excited kindergarteners.

The class had just finished their Star Assessments, a screening tool the city school district uses to monitor student performance. That meant Esperanza broke out the appropriately shaped decorations.

One small child raised his hand to answer, and Nuñez called on him. But the child stayed silent. Beside him, a classmate whispered, “He speaks Spanish.”

Nuñez translated the question, but the child remained quiet. His young classmate added: “Well, he speaks Spanish and English actually.” But on this day, it seemed, the youngster was too nervous to talk.

Making kids comfortable in whatever language they speak, and whatever culture they come from, is key to Esperanza Academy’s approach. On the walls of this kindergarten classroom, the teacher has hung the flags of Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic to represent the students with connections to those places. Staff spend time exploring the surrounding community as part of teacher training.

For decades, Esperanza Academy has served Philadelphia’s majority-Latino Hunting Park neighborhood. It’s grown from a small charter high school to a K-12 institution that serves more than 2,000 kids across three nearby buildings. Though any family in Philadelphia can apply to attend, the majority of students live within three miles of the school and around 90% of students are Hispanic or Latino, according to Nuñez and district data.

As Philadelphia’s Latino population grows and many Latino families say they feel left out of the district, Esperanza Academy has been in an unusually advantageous position to support those communities. Though it manages its own finances and operations, it’s part of the larger Esperanza organization, a 40-year-old faith-based organization that provides housing assistance, workforce development programming, legal services, and more in Hunting Park.

That approach, according to school officials, has made it much easier for the school to build trust and respond quickly to students’ and community needs.

When families need help with housing, Esperanza has resources for them. When a parent loses a job, Esperanza can help them train for a new one.

And in January, when Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents raided a car wash a few blocks away from the school right at dismissal time, arresting several workers, Esperanza made legal resources quickly available.

“It’s a full service situation,” said Jeana Davis, the school’s elementary school principal. “Families, community — you’re all in.”’

As the district grapples with how to serve immigrant families and Spanish-speaking students, Esperanza’s model is one example of how schools can support a community in difficult moments as well as celebratory ones.

Esperanza aims to build an ‘opportunity community’

The area around Esperanza Academy includes the second-poorest ZIP code in Philadelphia, with more than 40% of families there living in poverty, according to census data.

The aim of Esperanza, the school’s Evangelical parent organization, is to build an “opportunity community,” according to the organization’s founder, Rev. Luis Cortés Jr. That means showing residents that “you don’t have to be wealthy to have a good life,” he said.

Its academic programs are integrated into its network of resources, said Cortés. Along with Esperanza Academy, the organization runs a cyber charter school and a Christian college program.

There are other schools in the city attempting to provide similar wraparound support for families. The city’s community schools initiative, begun under former Mayor Jim Kenney, has some similarities. But at Esperanza, this approach has been crucial to the school since its founding in 2000.

“We’re far ahead, because we’ve been able to figure out how to integrate and still keep the walls,” Cortés said.

The other branches of Esperanza table at back-to-school nights and sometimes give presentations at the school’s regular family engagement nights. The school also trains neighborhood residents to work in the cafeteria and manage operations at its campuses.

Esperanza officials say these community connections contribute to strong student achievement. During the 2023-2024 school year, the most recent year of available data, 92% of Esperanza Academy’s high school seniors graduated, and nearly half attended college — significantly higher rates than at the traditional public school just a block away, Thomas A. Edison High School. Student achievement on state tests was fairly similar for both schools.

Researchers have examined similar models in studies on community schools, a broad term that typically refers to schools that partner with families and community organizations to provide resources beyond the classroom.

Anna Maier, a researcher at the Learning Policy Institute, said those studies show the approach is linked to better attendance and higher test scores, and could help improve achievement for students who might need it the most.

“We’re seeing that historically underserved student groups are benefiting the most,” said Maier.

As Esperanza has expanded, it’s unclear whether that growth has directly affected enrollment at nearby schools.

This year, as part of the opening of its new elementary school building, it enrolled 750 more students, as approved by its charter agreement with the district, said Nuñez. Meanwhile, Edison operates in a half-empty building, and enrollment at the nearby Alexander K. McClure Elementary has declined 20% in the past three years.

But there are still 4,000 families on Esperanza’s waitlist, Nuñez added.

For those families who send their children to Esperanza, the ICE raid at the start of 2025 tested the school and the people who work there.

“Families were calling, so we had to respond very quickly,” said Nuñez.

The school’s reaction was swift. School officials contacted their counterparts at Esperanza Immigration Legal Services and created resources for families to know their rights and to do if ICE agents came to the door.

Esperanza also printed thousands of special editions of Impacto, the newspaper it runs, to distribute with information about immigrant rights.

The raid shook many families and staff at the school, said Davis, the elementary school principal. Administrators referred families to Esperanza Immigration Legal Services, where they could get more help. The school also hosted training for teachers and spoke to students about what their rights are as well.

“The goal is to always keep the barriers away from the teacher so that you can just do the job,” said Davis, the elementary school principal. “That was really important to communicate: that we would carry that stress for them, that they did not need to carry that.”

To Nuñez, who spent decades working at the Philadelphia school district before joining Esperanza last year, the longstanding partnership the school has with Esperanza’s other programs has been invaluable.

But she said she also understands why it may not work for other schools to adopt a similar model. In many ways, the decades Esperanza has spent in Hunting Park building trust and community connection have equipped the organization — and through it the school — to meet this moment, she said.

“Principals in other traditional schools and charters that I’ve worked with, they have to be extra intentional to go out and develop these partnerships,” said Nuñez. “But we don’t have to do that here — it already exists.”

Correction: Sept. 23, 2025: A previous version of this story misstated which group runs the cyber charter school and college program. Esperanza runs those programs separately from Esperanza Academy.

Rebecca Redelmeier is a reporter at Chalkbeat Philadelphia. She writes about public schools, early childhood education, and issues that affect students, families, and educators across Philadelphia. Contact Rebecca at rredelmeier@chalkbeat.org.