Sign up for Chalkbeat Philadelphia’s free newsletter to keep up with news on the city’s public school system.

There were 873 pieces of paper in the box.

Eight hundred seventy-three death records for 873 children who had died in Sacramento County, California, between 2010 and 2015.

I spent several weeks reading every paper in that box during the summer of 2016.

I entered each name and cause of death into a spreadsheet. I was 23 years old and working on my first front page story at my first real newsroom job.

Black children made up a quarter of the box’s records, even though Black kids represented just 11% of the county’s under-18 population at the time.

Roughly a fifth of those children died in their sleep, and more than a third right before or after birth, according to our newsroom’s analysis. A little under 10% died by homicide, most of them shootings.

I spent a lot of that summer telling the stories of those children. I spoke to their parents, mostly mothers, and the church ladies and basketball coaches and neighbors who were trying to make sure no more children ended up in a coffin.

But I focused more on the sleep-related and perinatal deaths than I did on the fatal shootings. Maybe because the kids who were shot were a smaller part of the pool. Maybe because I was a health reporter, not a crime reporter. Or maybe because I found it too overwhelming to think about why children in my city were so often in the line of gunfire.

Still, questions about that box stayed with me for the next 10 years, across multiple jobs in multiple cities. Why these children? Why these neighborhoods? Why does it keep happening?

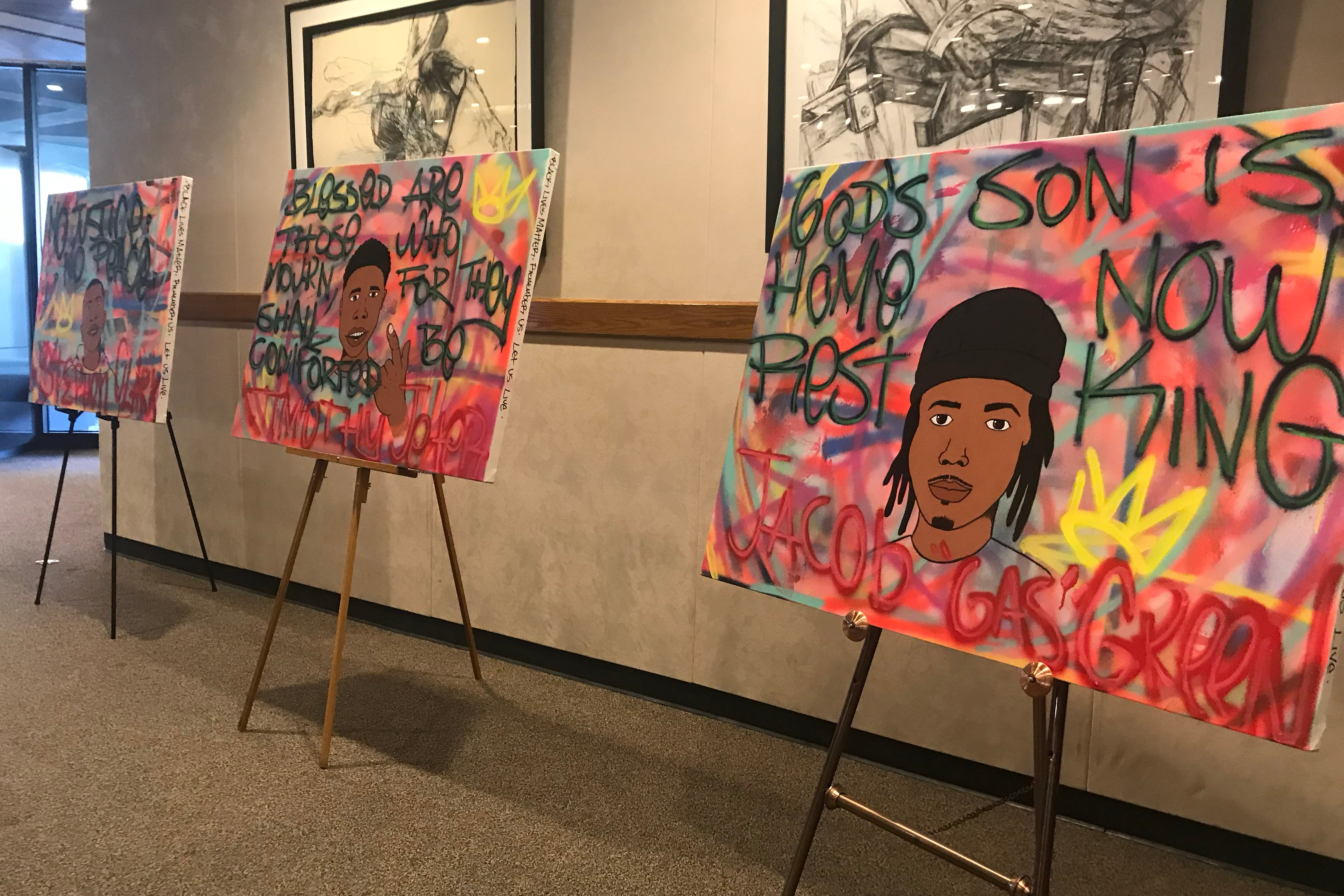

Those pieces of paper came to mind every time I covered a teen football player shot in broad daylight, an exchange of gunfire at a recreation center, or a child gunned down while riding his bike. The grief of the parents I talked to back in 2016 echoed in the interviews I conducted while covering gun violence prevention at WHYY in Philly, and in my ongoing coverage of young, unarmed Black men killed by police.

Nearly 10 years after opening that box, I’m starting my second full-time job as a gun violence reporter. It’s a position that remains heartbreakingly relevant in Philadelphia and other cities as the economic, racial, and health disparities driving the firearms crisis in America remain largely uncovered and unaddressed.

My goal is to remind people of something we lose track of in the deluge of numbers and newsclips about gun violence: that it’s a problem with a solution.

Lots of solutions, actually. Shootings are down dramatically since the height of Philadelphia’s gun homicide crisis in 2021.

That might be because of some things I witnessed when I started covering gun violence in 2022. An influx of city funding to grassroots nonprofits that provide safe spaces for kids after school. A group of teens learning to resolve conflict among their peers. A team of neighbors building a community garden after a 3-year-old was shot and killed while getting her hair braided on the block.

People are coming together to keep their children safe.

Still, 14% of fatal and nonfatal shooting victims in the past year were under 18, according to data from Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner’s office. That percentage has remained fairly consistent since 2021, even as the number of overall shooting victims declines.

Kids are not supposed to get shot.

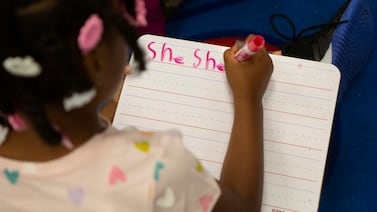

Kids are supposed to be able to walk to the library, or the rec center, or their school without being afraid for their lives. Kids are supposed to be able to learn, and dream, and plan for the future without passing through metal detectors or practicing active shooter drills.

So that’s why I’m staying on this beat, and looking specifically at our city’s youngest residents in a space where they spend a great deal of their lives — school.

What are schools doing to keep kids safe on their way to and from campus? How are school administrators keeping weapons out of school buildings? What are the tools and processes for identifying risks, and are they working?

Beyond that, how are schools helping students’ families address trauma, poverty, and other factors that lead to violent behavior and victimization outside the home?

And as firearm homicides decline in Philadelphia, how can children heal from the losses that have rippled through their communities over the last five years?

These are questions I hope to spend the next year exploring at Chalkbeat Philadelphia. I want to do it as I always have — by listening to the people directly affected by the gun violence crisis, including the children who grapple with it before, during, and after the school day.

I want to envision a Philadelphia where children never become part of the city’s death count.

Schools play a role in keeping kids safe, and so does each and everyone one of us. Stay part of the conversation, and learn what solutions are underway where you live.

Sammy Caiola covers solutions to gun violence in and around Philadelphia schools. Have ideas for her? Get in touch at scaiola@chalkbeat.org.