Tennessee school leaders were among the last to learn about Ford Motor Co.’s plan to start building electric vehicles in West Tennessee, but they’ll be expected to be on the front lines of preparing skilled workers for the historic endeavor.

Ford, with its South Korean battery partner SK Innovation, will bring some 5,800 new jobs to the region to begin producing Ford’s next generation of electric pickup trucks in 2025.

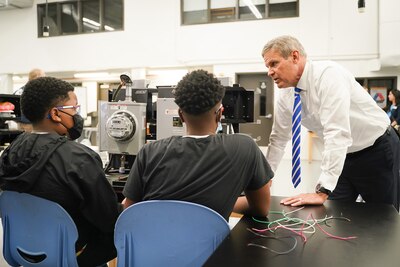

This week’s announcement came from Gov. Bill Lee, a mechanical engineer businessman who has championed career and technical education, work-based learning, and apprenticeship programs since taking office in 2019.

The focus of those programs will have to sharpen now in K-12 schools across West Tennessee, where droves of manufacturing jobs dwindled for decades as companies moved those operations overseas to save money.

The new jobs — to build electric vehicles — will require different skills than those in traditional manufacturing.

“It takes a lot of math, reading, and critical thinking. It’s not a lot of lifting or repetitive manual tasks,” said Ann Thompson, director of workforce development for the state Department of Economic and Community Development.

Tennessee plans to launch a trade school at the $5.6 billion Ford complex, which will be built on the Memphis Regional Megasite in Haywood County, about 25 miles northeast of Memphis.

The school, operated by the state Board of Regents, will join the state’s 27 other technical colleges to help train many of the project’s first workers. Some of those campuses already have courses specializing in electric vehicle manufacturing.

But to provide a sustainable supply of workers, Tennessee must reach far beyond technical schools, community colleges, and universities — beginning with school systems in Shelby, Madison, Haywood, Fayette and Tipton counties.

“Everybody is going to have to up their game with career and technical education and work-based learning,” said Amity Schuyler, senior vice president of workforce development for the Greater Memphis Chamber of Commerce. “It’s going to be more important than ever to introduce students early to real-world work experience.”

Thompson, with the state’s economic development office, said teachers also will have to understand the skills needed for occupations associated with electric vehicles.

“They’ll need a tremendous number of engineers, but not everybody has to be an engineer to be employed by these companies,” she said of expertise that will include supply chains, material handling, logistics, production, information technology, security, and much more.

Growing automotive cluster

With an abundance of low-priced land, trainable workers, and government incentive packages, Tennessee has been reshaped by the automotive industry since Nissan opened an assembly plant in 1983 on farmland near Smyrna, south of Nashville. General Motors followed two years later with its plant in Spring Hill, southwest of Nashville, and Volkswagen began building sedans in Chattanooga in 2011. Add in about 900 suppliers that have located in Tennessee and the industry today employs more than 75,000 Tennesseans.

The addition of Ford in the town of Stanton (population 438) brings a major automotive manufacturer to West Tennessee for the first time.

The region hasn’t reaped many benefits from the state’s corporate and industrial recruitment successes. Ford and SK Innovation will be the first tenants on the 4,100-acre Memphis megasite which, except for improvements to infrastructure, has laid fallow since the state bought the property in 2009.

Memphis — as the region’s only major city and home to Tennessee’s largest public school district and a declining manufacturing sector — has seen its student test scores lag most of the state and its population shrink. That’s all under the weight of widespread generational poverty fueled by racial inequality and a “permatemp” economy heavy with contract and temporary workers.

While salary information isn’t yet available for the Ford project, state Sen. Raumesh Akbari basked in the news that West Tennesseans will build electric trucks in a few years — and what it will mean to encourage children from low-income families to pursue their studies.

“It’s actually difficult to overstate the significance of this announcement and the potential for transformative change that an underserved community will see from this historic investment,” said Akbari, who represents Memphis.

The focus now should be equipping students to take advantage of future opportunities driven by electric vehicles, said Schuyler, with the Memphis chamber.

“It’s workforce, workforce, workforce!” she said. “The immediate need is to build the plant facilities. The long-term goal will be to provide the workers needed at scale for when production begins.”

Tennessee’s campaign to land the Ford project was so confidential that state officials used multiple code words internally in the recruitment effort. No advance conversations were held with local school leaders, but the state provided Ford with lots of information about schools.

“They were very interested in the number of students, the number of work-based learning programs, apprenticeships, and examples of successful business partnerships in West Tennessee,” said Thompson. “Overall, they seemed most concerned about having a partner that recognizes it’s going to take all of these entities coming together to build the workforce they’ll need.”

Joris Ray, superintendent of Shelby County Schools, said new opportunities with Ford align with the Memphis district’s ongoing Reimagining 901 initiative to revamp academic offerings, with an emphasis on business and community partnerships.

“We’re transforming our college and career technology program around STEM, manufacturing, information technology, health sciences,” Ray said. “We would love to sit down with Ford leaders to talk about what they need from us to ensure our students are ready to go.”

Near the future plant site, the 2,800-student Haywood County Schools has responded to existing local industry needs by offering courses and certifications in industrial maintenance, welding, coding, and health sciences.

That list will grow with Ford’s arrival, promised Superintendent Joey Hassell.

“We will work hard to be flexible within our career offerings,” he said. “What this means for students in Haywood County and all of West Tennessee is you can graduate high school, pursue post-secondary opportunities, and live and work in the community you grew up in.”

Driving change

Since auto manufacturing arrived in Chattanooga in 2011, leaders with Hamilton County Schools have worked closely with Volkswagen to change the conversation around workforce development.

“When big business comes to town, there’s an expectation that the local school system will help to provide an educated, well-trained workforce because it’s a lot easier to hire locally,” said Blake Freeman, the district’s academic officer overseeing partnerships with industry.

“At the same time, our community should expect that students are being equipped to move into high-skill, high-wage jobs. Everybody stands to benefit — including the community — because students who go on to well-paid jobs generate more tax revenue that then pours back into our schools,” Freeman said.

In partnership with Volkswagen, the Chattanooga district operates 32 e-labs across all of its elementary, middle, and high schools. The goal is to develop essential workforce skills like communication and problem-solving as students learn to design and test prototypes through digital fabrication technologies.

For a few dozen high school students, the district also operates an on-site mechatronics academy at the Volkswagen plant. There, the students learn hands-on about the automotive industry and get training in robotics, computer programming, and coding.

“I would encourage any school district that stands to gain from a big announcement like Ford’s to begin having conversations as early as possible with your local chamber of commerce, as well as contacts for the company, “ Freeman said.

“You want to know their profile for future employees,” he said, “and you want to stay nimble.”