Holding back tears, Teresa Short described her struggles trying to help her son, a preschooler who needs special education services, catch up after COVID-caused school disruptions.

Their school district, Fayette County Schools in Somerville, was only able to offer summer academic programming to children in K-12, she said. The reason, she was told, was limited funding.

“So I had to go and find private schools that I could try to get him in, paying out of my pocket to try to get him an education and get him caught up to where he needs to be,” Short said.

Given the chance to weigh in on how Tennessee should approach its first school funding formula overhaul in 30 years, Short advocated for providing more money to schools overall and making sure more of it is steered toward students in special education.

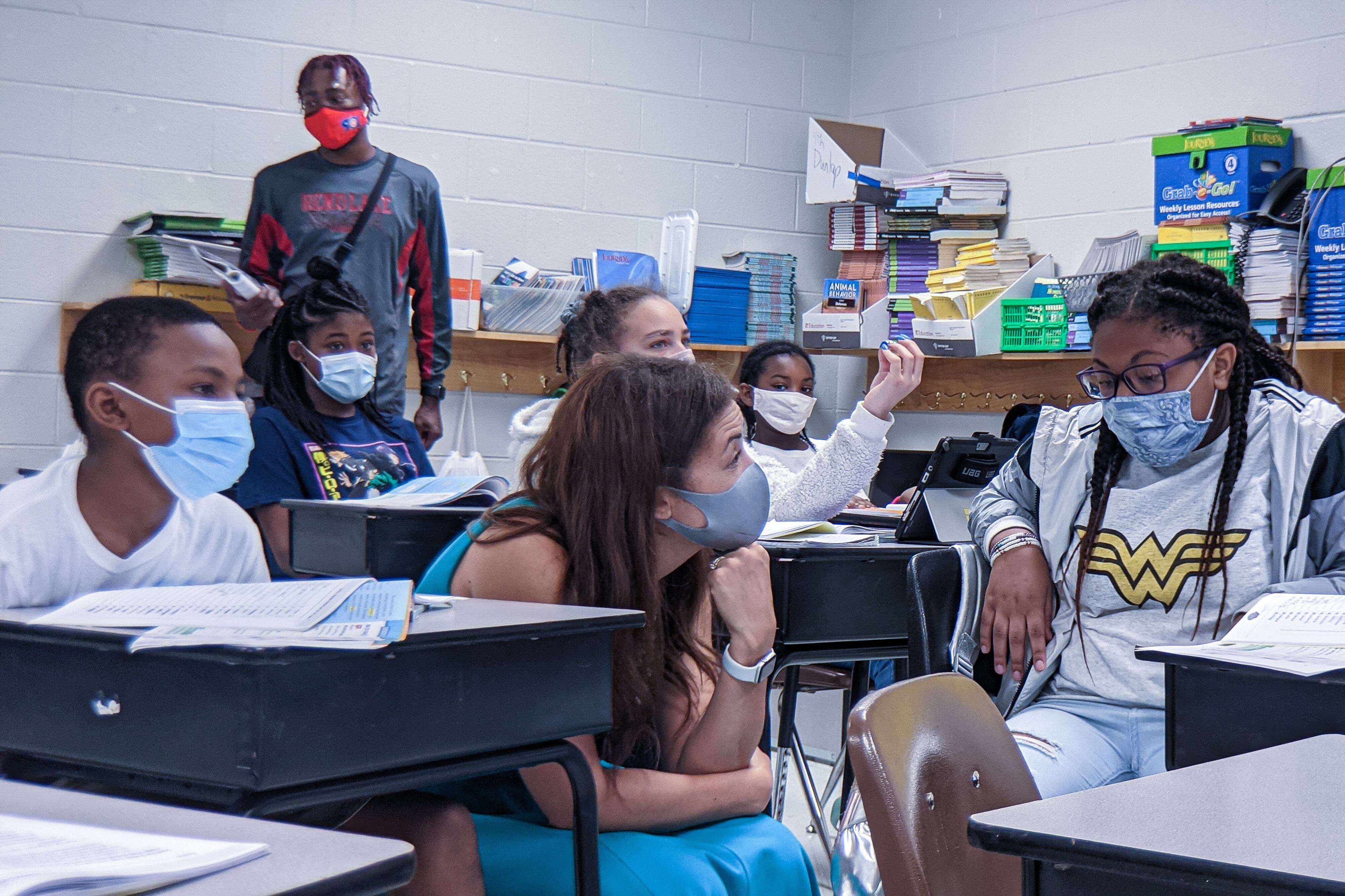

She joined a packed room of parents, students, educators, administrators, school board members, and activists Thursday at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis for the second of eight town halls the state education department is staging to gather input on the issue.

In remarks ahead of Thursday’s town hall, Tennessee education commissioner Penny Schwinn encouraged attendees and those tuning in through a live stream to make their voices heard as the state reviews how it should fund public education.

“A really good process for policy development has to include everybody. All of us are Tennesseans, we all have a voice in this,” Schwinn said. “Every single perspective and viewpoint should be counted and considered no matter where you live, no matter what your perspective.”

Tennessee’s school funding formula is based on a complicated rubric of 46 components that determine how much state money is distributed to school systems to pay for needs ranging from salaries for teachers to textbooks, technology, and bus transportation. Districts have flexibility on how to spend that money.

Republican Gov. Bill Lee is pressing to revamp the system to emphasize funding individual students instead of school systems, which could force the state to do student-by-student calculations and might make it easier for Tennessee to start a private-school voucher program.

The goal is to come up with a proposal for the Tennessee General Assembly to consider after convening in January.

The Memphis town hall Thursday came on the same day a national research group gave Tennessee poor marks for the “unfair” way it funds schools.

The Education Law Center’s “Making the Grade 2021” report gave Tennessee failing grades for state and local school funding level per pupil and for its overall effort to fund PK-12 education as a percentage of the state’s economic activity.

Tennessee has the seventh-lowest per pupil funding level in the nation, according to the report, with an average of $11,139 — nearly $4,000 less than the national average. And while the state’s fiscal capacity is lower than the national average, Tennessee also makes a lower than average effort to fund schools, the report found.

The Education Law Center also gave Tennessee a “D” for the way it distributes school funds. On average, high poverty districts in the state receive 3% — or $389 — less per pupil than districts with low poverty levels, the report found.

Referencing that point of the report, Bob Nardo, executive director and founder of Libertas School, argued at Thursday’s town hall that the state’s new funding formula needs to provide dollars based on a student’s individual needs and must allow that money to follow them to the school of their choice such as Libertas, a Montessori charter school that serves nearly 500 students in Memphis’ Frayser neighborhood.

With a high concentration of students who are economically disadvantaged and who receive special education services, Nardo said Libertas needs extra funding to meet the needs of its students.

But under Tennessee’s current formula, “a middle class typically-abled child has the same amount of funding as a child with cerebral palsy in a high-poverty school district,” Nardo said. “It’s ludicrous.”

Other attendees of Thursday’s town hall urged state lawmakers to keep partisan politics out of the school funding formula and simply provide more dollars to public schools for bare necessities like books, school supplies, and school buildings.

For over 25 years, Peggy Watkins said she has “subsidized” schools by purchasing supplies for teachers’ classrooms not included in the budget, or books so each student could have their own copy. It shouldn’t be that way, Watkins argued.

“Let’s use the money where it counts the most — investing in our future, our children,” she said.

Others referenced a recent spate of gun violence, and children with gunshot wounds, in Memphis, and contended schools need increased funding for counselors, social workers, and school nurses. Some also argued teachers need increased support in the classrooms to better support students’ emotional and social well-being.

LaCanas Brandon, a teacher in the Millington Municipal School District, said she often feels unequipped to support students with so many personal challenges. Many, she said, struggle with the trauma of having parents in jail and being raised by grandparents, aunts, uncles, or older siblings.

“There are resources they need that are deeper than just the teacher, the one counselor, the principal,” Brandon said. “Funding for our schools is not successful if our kids can’t be successful.”