Claire Manos plans to shop for supplies and a few clothes to get ready for a new school year next month in Tennessee, but one major item isn’t on her back-to-school list: getting vaccinated against the coronavirus.

The 14-year-old became eligible for the vaccine in May when it opened to children ages 12-15, but Claire said she’s not ready for that step, even if scientists recommend it.

“I guess I’m just waiting to see how everybody does with it,” explained the incoming freshman at Wilson Central High School in Lebanon, just east of Nashville, while shopping with a friend Thursday.

With less than 38% of its eligible residents fully vaccinated — and only 2% in Claire’s age group — Tennessee will be one of the first states to reopen schools while navigating COVID’s more contagious Delta variant, now the nation’s dominant strain of the respiratory virus.

The new academic year begins in late July or August, depending on the district, but all schools will deal with the same challenges when it comes to keeping their students and staff safe and healthy: skepticism about the new vaccines, politicization of the pandemic, and general COVID fatigue.

The convergence of factors has public health leaders worried, with at least one prominent infectious disease expert recommending that unvaccinated Tennesseans get their shots as soon as possible.

“Tennessee may be known as the Volunteer State, but most Tennesseans have not stepped up to get vaccinated,” said Dr. William Schaffner, professor of preventive medicine at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville. “Sadly, we are a very undervaccinated state, and that makes us vulnerable, including in our schools.”

The Delta variant is just beginning to get the attention of school leaders who have focused this summer on providing extra state-required learning programs to counter more than a year of pandemic disruptions, said Dale Lynch, who heads the state superintendents organization.

But medical experts have been tracking the mutation since its discovery in India in December. Evidence shows the strain spreads more quickly than previous variants and is most dangerous for people who aren’t fully vaccinated. States with the lowest vaccination rates — like Tennessee — will be hit the hardest, the experts warn.

“The bottom line is that the more people who are vaccinated, the safer we’ll be and the safer our schools will be,” said Schaffner, also medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

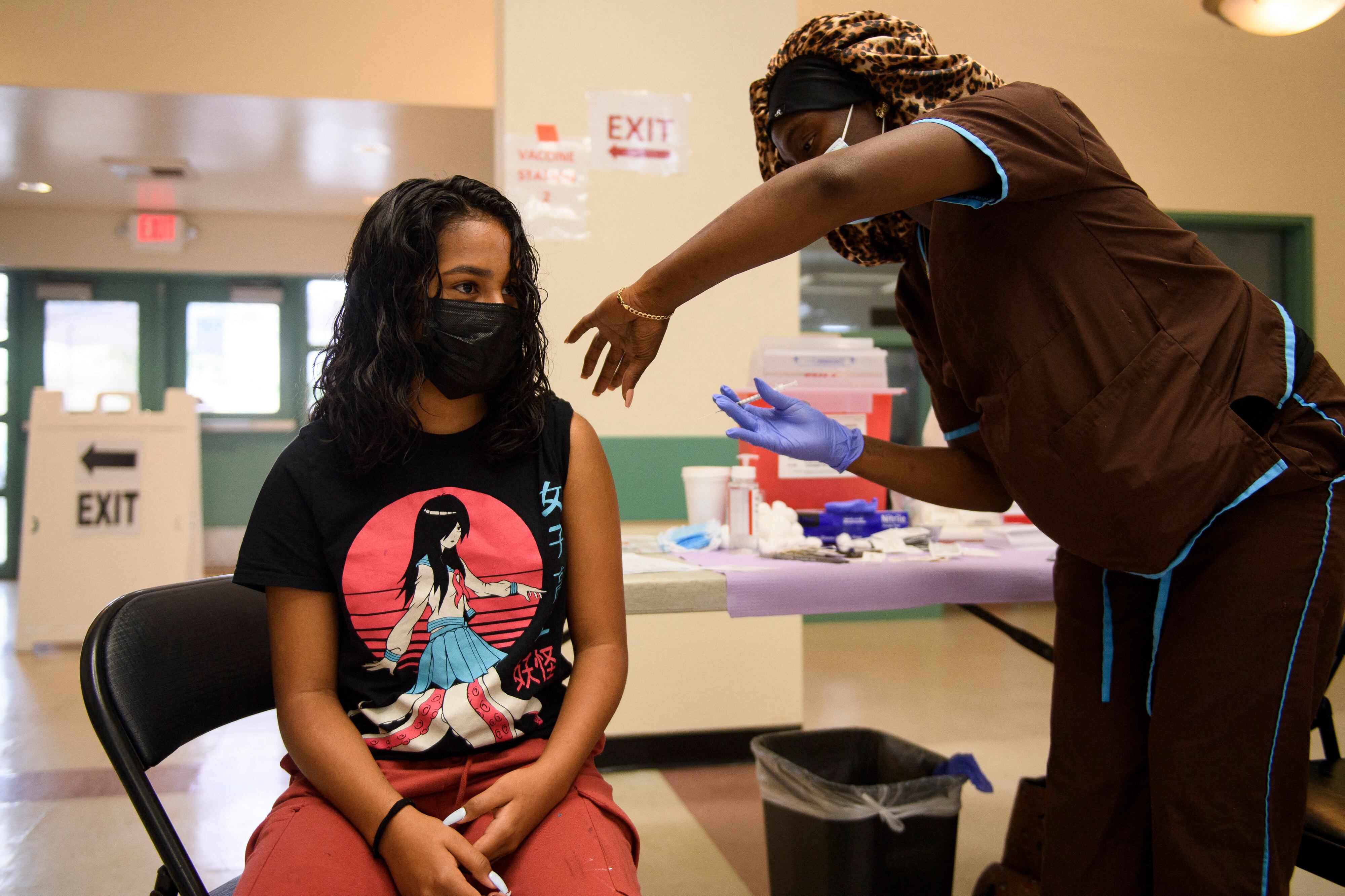

It’s especially important for unvaccinated parents or school employees — from teachers to bus drivers to custodians — to get vaccinated, as should children 12 or older with a parent’s permission, so that schools don’t become breeding grounds for the Delta variant, Schaffner said.

But that message hasn’t been delivered consistently across Tennessee, where a recent poll found party politics dominate residents’ attitudes on key public health and social issues in the deep red state. The poll, conducted in May by Vanderbilt’s Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions, found Republicans were less likely than Democrats to get vaccinated and far more likely to view the pandemic as largely over.

Republican Gov. Bill Lee, who got vaccinated quietly in March with no public announcement, declared in April that COVID-19 is “no longer a statewide public health emergency.” Calling vaccines a personal choice, he has been mostly mum recently on the need for them. He’s also rejected strategies embraced by some Republican governors to give cash and other vaccination incentives to hesitant residents.

This spring, the GOP-controlled legislature passed several bills that also sent mixed messages on vaccinations. One prohibits government entities, including public schools and universities except those with healthcare studies, from requiring COVID shots. No such mandates exist, but legislators argued for a preemptive law to ensure that personal liberty would trump public health, even during a pandemic.

Another new law requires that any information shared with students or parents about state vaccination requirements for communicable diseases must now also include information about religious exemptions.

Last month, several Republican lawmakers threatened to dissolve the state health department over allegations it was targeting minors for vaccinations without parental consent.

“Market to parents, don’t market to children — period!” Sen. Kerry Roberts, a Republican from Springfield, told Dr. Lisa Piercey, the state’s health commissioner, during a legislative hearing.

As a result, the department — which recently returned some 3 million vaccine doses to the federal government because of low demand — instructed its county-level employees to halt vaccination events focused on adolescents and stop online outreach to teens, according to department emails obtained recently by The Tennessean.

Senate Minority Leader Jeff Yarbro, a Democrat from Nashville, called the state-level developments “mind-numbing” and predicted they will set the tone for local conversations that school officials must now have in their communities.

“Politicizing public health decisions never makes sense,” Yarbro told Chalkbeat. “It’s sad that our legislature, just like our governor, hasn’t sent a consistent, easy-to-understand message to Tennesseans so they know how to keep themselves, their families, and their communities safe.”

Those conversations are sure to include whether to reinstate mask mandates that, despite some local pushback, were fairly standard last school year based on recommendations from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In new guidance for next school year issued on Friday, the CDC said young students should continue to wear masks at school, but vaccinated older students and teachers don’t need to.

With the exception of Shelby County Schools, the state’s largest district, most masking school systems switched to optional or limited face coverings for summer programming after the vaccine became easily accessible. District leaders in Knoxville and Chattanooga already have announced they won’t require masks this fall, which Schaffner says they should reconsider.

“Especially for younger ones who aren’t eligible to be vaccinated yet, it’s important for schools to stick with well-established ways that will keep them as low-risk as possible,” he said. “That means mask wearing, good hand hygiene, social distancing — in addition to older people around them getting vaccinated.”

Last week, the Tennessee State Board of Education offered some public health options for the coming school year with an emergency rule that lets districts provide temporary remote instruction to students who are quarantined after testing positive or being exposed to COVID.

Chase Werkheiser, a 16-year-old Nashville student, plans to follow all the scientific recommendations when he returns in August to Martin Luther King Jr. Magnet School. He and his older brother, Chris, wore face coverings while visiting a local mall Thursday to interview for part-time jobs. They’re also fully vaccinated — a decision they viewed as a no-brainer.

“I just didn’t want to take the risk of getting COVID,” said Chase, “and I trust the vaccine enough.”