When Diarese George reflects on the six years he spent as a teacher in the Clarksville-Montgomery County School System, he recalls a yearly event that was particularly frustrating: Recommendation Day, when teachers advised students on classes they should take the next school year.

Time and time again, George recalled, teachers pushed white, affluent students to take Advanced Placement or dual enrollment courses, while students of color and those from economically disadvantaged backgrounds — who didn’t have the highest GPAs but needed the opportunities most — were continually overlooked.

George intervened in the inequitable practice, creating his own dual enrollment course for the students who may have been overlooked. Dual enrollment classes allow students to earn college credit in high school.

George shared this story about the importance of Black male educators who disrupt the status quo at the Memphis Education Fund’s fall conference, titled “Eradicating the Odds in Education: The Intersection of Racial Justice, Pedagogy, and Emotional Wellness.”

The event, held virtually Wednesday and Thursday, drew about 250 local educators and advocates, as well as nationally-renowned education experts like Dena Simmons, Goldy Muhammad, and Bettina Love, who spoke on topics ranging from racial justice in schools and culturally responsive teaching to social-emotional learning and the need for more Black male teachers.

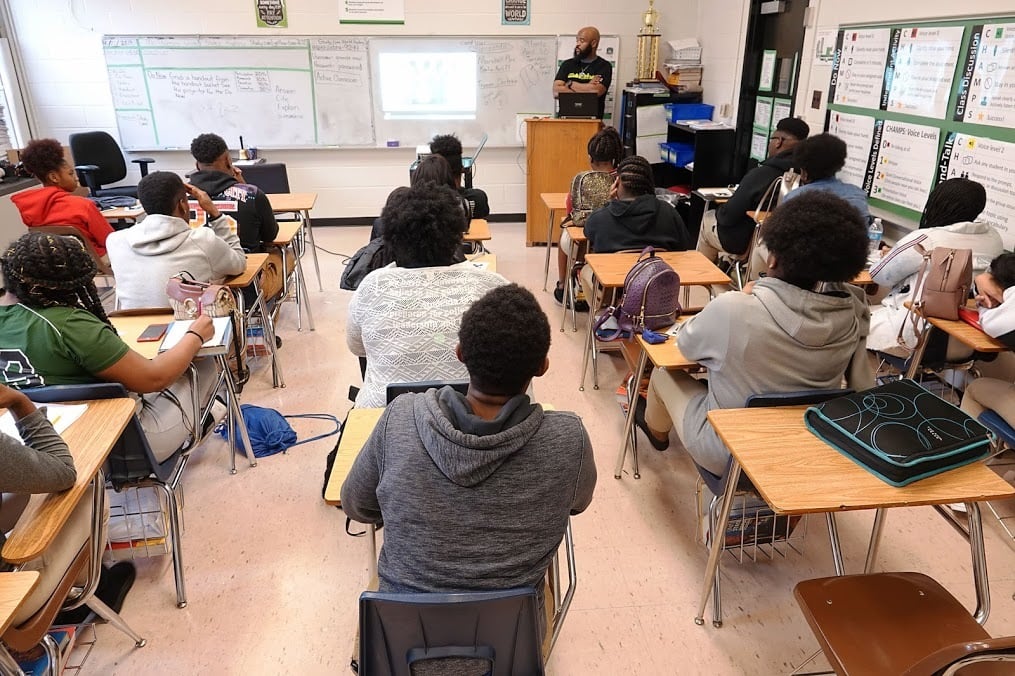

Although students of color represent more than half of the United States’ student population and research shows Black students benefit greatly if they have even one Black teacher, a 2016 study found only 7% of the teacher workforce is Black, and Black men in particular comprise 2% of the national teacher workforce.

Like many of his students in Clarksville-Montgomery, he knew what it was like to be overlooked by his mostly white teachers. As the only Black educator at the time, he also knew the positive impact even one college preparatory course could have on students of color who maybe weren’t considering post-secondary education.

So, George adopted a different practice when recommending students for his dual enrollment class. He invited students based on their potential — both in the class and in the future — rather than their merit, allowing him to “level the playing field.”

“The people close to the problem have to be centered in finding solutions,” said George, who went on to launch the Tennessee Educators of Color Alliance and now serves as the organization’s executive director. “We’ve got to listen and learn from people who have the lived experiences and the institutional knowledge and capacity to be able to drive change forward.”

As it turned out, George’s idea worked: Over time, an increasing number of his students who weren’t previously considering college or other post-secondary education options changed their minds.

The benefits of Black male educators aren’t just academic, though. To Patrick Washington, founder and CEO of ManUp, a Memphis teacher preparation program that aims to help recruit and retain more men of color to the field, it’s much more than that.

Because they’re better able to relate to one another, Washington said, Black male teachers can forge relationships with Black boys in a way others can’t, and they can work together to make school work for them both.

That’s why Shelby County Schools partners with organizations like ManUp and the Tennessee Educators of Color Alliance, said Michael Lowe, district director of equity and access.

As of 2019, Black men made up about 12% of Shelby County Schools’ teacher workforce. Although that’s six times more than the national average, district leaders say it’s not enough when Black boys represent about 38% of the school population.

“We know that it’s important to not only have windows but mirrors in our schools,” Lowe said, explaining that students need to see both reflections of themselves in the classrooms and views of new cultures and identities.

Terence Patterson, president and CEO of the Memphis Education Fund, said the organization decided to hone in on the dearth of men of color in the classroom and other education equity issues in light of the ongoing pandemic, which continues to devastate children academically, socially, and emotionally — especially children of color and those who are economically disadvantaged.

“Certainly no one is happy with the recent test score data that we’ve seen,” Patterson said. “But from our standpoint, if we’re able to provide a platform for people to talk about the aspects of pedagogy that could even in a small way improve how our students, primarily Black and brown students here in Memphis, are getting access to curriculum and learning and improving, I think we’ve done a good job.”