Kelly King was able to do something this summer she’d never been able to before: pay students to help others.

King, who works for the school district on Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula, used federal COVID aid to hire three rising high school seniors to staff a booth at a riverside park. There, as crowds flocked to a farmers market and free concerts, the students told residents how local schools could help families experiencing homelessness and offer other kinds of support.

The high schoolers, each of whom had experienced homelessness themselves, earned just over $10 an hour for the community engagement work. For two of the teens, it was their first paid job.

“We were very intentional about doing things that had not been done before,” King said. She noticed that the work taught the students customer service and financial skills, and when students reflected on their experience, they said it boosted their confidence, too. The paid job “made them think more positively about what was possible for their futures,” King said.

Across the U.S., schools are using their influx of COVID relief money in an innovative but overlooked way: to offer paying jobs to students. Programs like the one in Alaska are an example of how the funding is allowing schools to get creative with how they offer direct help to young people and expose them to new career paths — benefiting both teens looking for work and schools in need of staff.

“More career preparation, or even thinking about careers, is quite a good thing at early ages,” said Mary Elizabeth Collins, a professor at Boston University who has studied workforce development for vulnerable youth. “There are a lot of potential career pathways available to young people, and we as a society don’t do a great job of letting them know the range of things that they could go for, and what they need to get there.”

School leaders say the money is especially helpful for teens who can’t afford an unpaid internship, or who are struggling to balance their schoolwork with a late-night part-time job. If teens are working as tutors or mentors, the jobs also provide an academic and emotional boost for students’ younger peers. To work best, programs should offer students plenty of adult guidance, especially if they are working with younger children, Collins said.

When the Houston school district launched a peer tutoring initiative with iEducate, a local nonprofit, officials there specifically targeted students interested in education. Using COVID relief funds, the district is paying its high schoolers and local college students, many of whom are recent graduates, $14 an hour or more to tutor elementary schoolers.

It gives tutors “an opportunity to build those relationships with our scholars, to help with that learning loss from COVID in our schools,” said Joseph Williams, a district administrator who oversees the tutoring initiative. “It also gives them that experience to see what teaching is about, and hopefully build a pipeline of future teachers.”

The district has hired student tutors in the past, but the new funding dramatically expanded the support the district could offer. This summer, high schoolers and recent grads worked with 21,000 elementary schoolers, and the tutors are getting ongoing training in skills like managing a classroom and lesson-planning.

So far Houston schools have paid $560,000 to their student tutors, and officials budgeted another $2 million for the upcoming school year. Some 200 tutors will be working in schools as of next week, and the district is still looking for several hundred more.

In Tacoma, Washington, the district is spending $450,000 in federal relief on a jobs program that pays teens to coach elementary school sports and to tutor their younger peers.

Before the pandemic, students could volunteer to coach, but now high schoolers can be paid $1,000 for six weeks of work, with the district and city splitting the cost. That’s opening up the job to students who wanted to coach before but couldn’t afford an unpaid role.

The district also is paying high schoolers a $500 stipend to tutor elementary schoolers in math and English after school. Officials piloted the initiative with 34 student tutors last year, and plan to expand it this year. Tutors get specific training on how to help younger students with their homework in those areas.

“We’re not just dropping students in and saying ‘OK, go tutor,’” said Kathryn McCarthy, a spokesperson for Tacoma schools. “Our goal was just to think about: What can we do to help students who are interested in the profession of teaching gain some depth of knowledge? So really focusing on how to provide some instruction.”

Not all new jobs initiatives have that educational component. Faced with staffing shortages, some schools have started hiring students to work in cafeterias or maintain school grounds, NBC News reported last month — jobs typically held by adults that some educators fear are less likely to serve students’ career ambitions.

“Rather than treating it as low-paid labor,” said Jake Leos-Urbel, who has researched New York City’s summer youth jobs program, schools should be “treating it as an educational, youth development experience, and thinking about the adults who are going to mentor and support youth in that work.”

That’s the approach being taken by Memphis-Shelby County schools, where officials are using federal COVID money to offer students paid internships within the district and at local businesses.

Lori Phillips, who heads the district’s student, family, and community affairs work, said the initiative helps fill several gaps. While there are several summer work programs in the area, few offer job exposure during the school year. And at $15 an hour, the program also pays more than the fast food jobs many teens have, without any late-night schedules — so students can stay on top of their homework and participate in extracurricular activities.

The initiative also includes Saturday training sessions where students dress up in business clothes and work in small groups with local leaders on skills like interviewing and setting up a bank account.

The district had wanted to launch something like this for some time, but the federal COVID money sped up the work, and made it more equitable, too.

“You may have some businesses that are interested in hosting two or three students, but they may not be financially equipped to be able to pay those students,” Phillips said. “We wanted to make sure that regardless of where you are, all students are getting paid the same amount.”

The district spent about $360,000 to pilot the program last school year and this summer — employing more than 1,000 students — and has set aside at least $1 million to expand the initiative this year. Phillips hopes 1,000 students can get internships each of the fall, winter, and spring sessions.

The federal funds have also meant that schools can pay students for their expertise.

In Virginia’s Roanoke City Public Schools, Malora Horn set aside COVID relief money to hire a peer support specialist to work in the district office that supports homeless students and families. The specialist, who experienced homelessness as a young person, will recruit students to serve on a new homeless youth advisory council. Often these kinds of roles are unpaid, but Horn plans to offer students a stipend or gift cards to participate.

“This gives them a safe place to have them share their thoughts and ideas of other services that they may be needing, or challenges that they’re having that maybe we haven’t thought of,” Horn said.

Teens who’ve gotten to participate in these programs say they’re grateful for hands-on work experience.

As part of Houston’s program, 19-year-old Leonardo Cuellar has been tutoring students at an elementary school not far from where he grew up, while balancing college classes. It’s been a chance to test out teaching with a safety net, since he’s partnered with a classroom teacher.

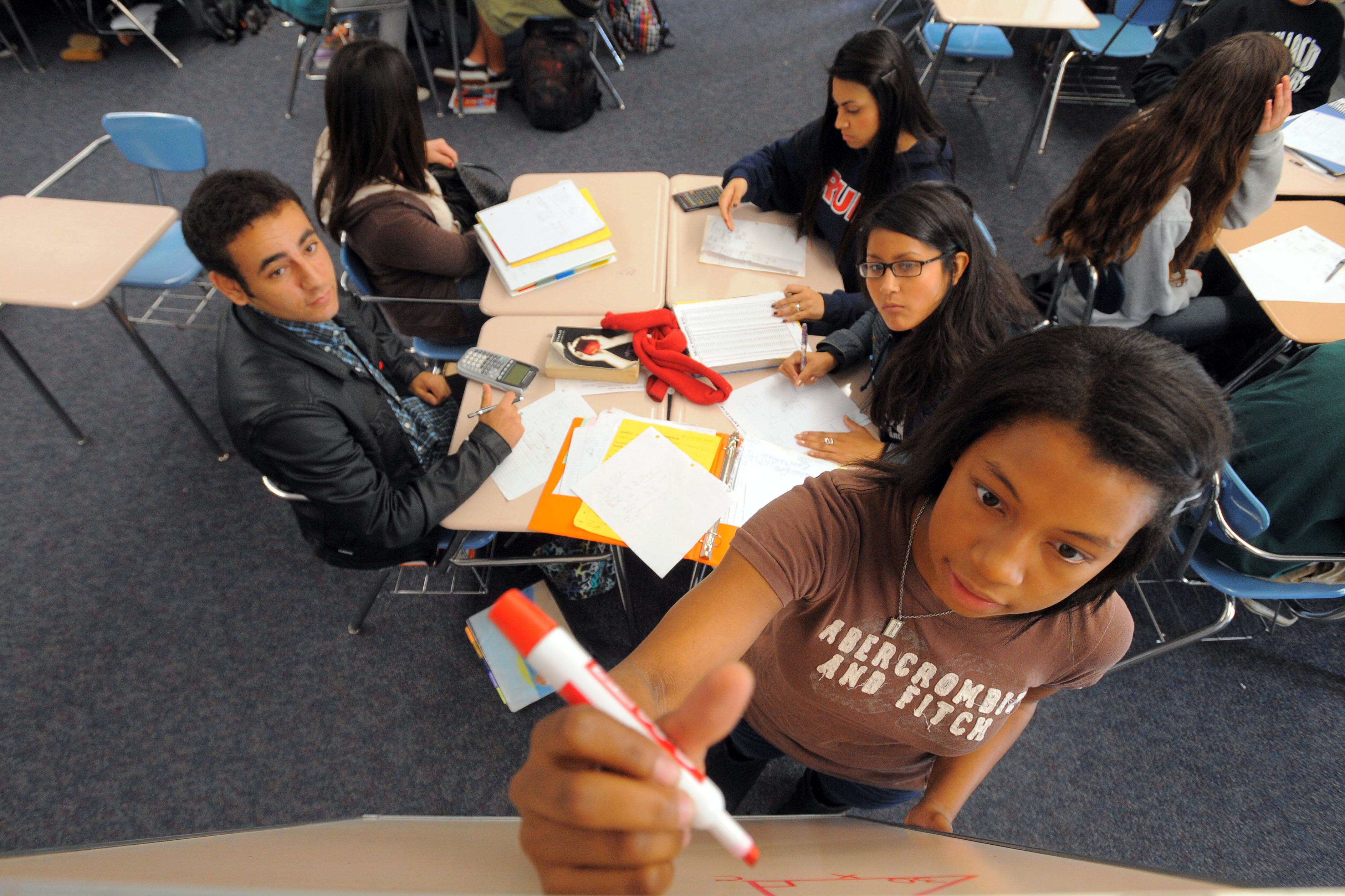

Over the last year, he’s worked with small groups of students on their math and reading skills in both English and Spanish. When his struggling second graders improved in math, his partner teacher told him it was thanks to the weeks he’d spent helping them practice skills like subtraction on a mini whiteboard.

“This has made me sure that I wanted to do this,” Cuellar said. “When I was a kid, I didn’t have that help, so being that person to be able to help them really feels good.”

Kalyn Belsha is a national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.