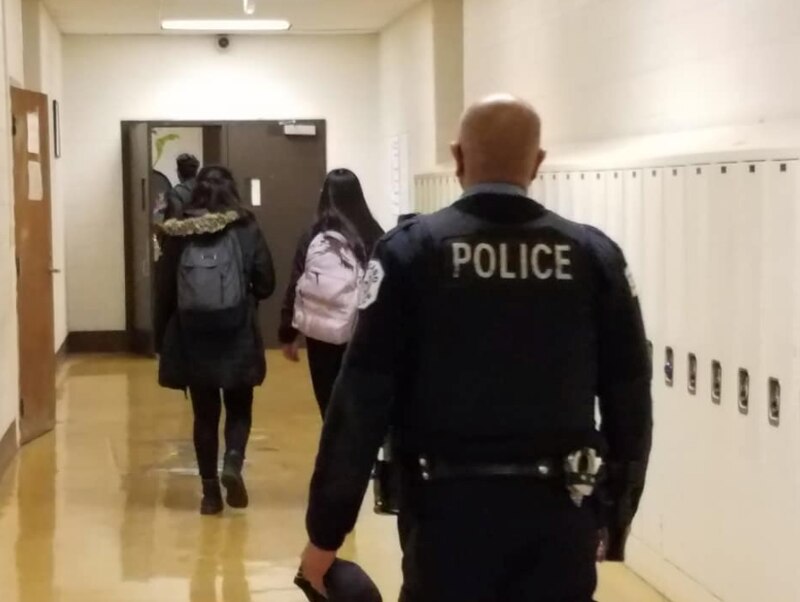

As young protesters in Chicago joined those across the country calling for an end to school policing, district leaders hastily called upon local school councils to decide whether to keep police on campuses and gave them an Aug. 14 deadline to make the decision.

But the process so far underscores long-standing issues around the transparency of the groups, how much they are supported and trained, and lackluster participation.

Reporting from 16 schools that so far voted on or discussed the issue shows that some councils failed to post meetings publicly or follow other rules that allow parents and community members to participate. Others tried to limit media access or public discussion.

This week alone, at least one council voted to retain police in schools, but the meeting wasn’t posted publicly online. Another voted before allowing public comment, and a third was in violation of rules that require the councils to place all planned votes on their agenda and post minutes online after meetings. One council ended its meeting abruptly after a reporter logged on and tried to identify herself, saying it would continue the meeting privately at another time.

By the middle of the week, Chicago Public Schools had released a toolkit and held an informational meeting in an effort to clarify the rules. But the district does not centrally track the dates of meetings, times or agendas, which leaves parents, students, and reporters to rely on the record-keeping at individual schools. That often means scrambling to find a meeting, or struggling to figure out how and why a decision was made.

According to the state’s law establishing the councils, the groups must hold at least two meetings a year and follow Illinois’ Open Meetings Act, which requires them to post an agenda publicly 48 hours in advance of a meeting.

Even prior to the latest votes, an analysis of the 70 schools with police officers show that 39, or more than half, have not posted online an agenda or minutes from any meeting this calendar year. Also, only 32 of the councils provided meeting dates or notices online this calendar year, all in violation of rules set forth by the school district.

David Greising, president of the Better Government Association, said the meetings act is one of two key tools — along with access to records — of public accountability.

Sometimes a body doesn’t adhere to those laws, said Greising, whose organization has filed lawsuits to encourage government transparency. But when there are multiple examples of a lack of transparency it’s no longer incidental. “That is a systemic problem,” he said.

Asked Tuesday at a press conference about reports that some councils weren’t posting meeting details and leaving communities without a mechanism for participation, Mayor Lori Lightfoot said it was the individual groups’ responsibility to inform their communities about the meetings, not the school district’s.

“Typically, when and how and what the circumstances are that those local schools councils are meeting is controlled by them, not by the central office at CPS. But we’ll certainly look into it if it’s an issue,” said Lightfoot who has opposed the wholesale removal of police officers from schools and thinks the decision should be the purview of the councils.

Asked directly about violations of its rules, Chicago Public Schools did not immediately provide comment, nor did it explain the reasoning for not centrally tracking meeting times and other information.

Councils were granted the authority to retain officers as part of a package of federally mandated reforms. Last summer, all councils voted to keep police, though some participants complained the votes were rushed or didn’t follow proper voting procedure at the time.

Originally designed to offer communities a voice in school decision making, the councils have the power to hire and evaluate the principal, approve a school’s annual budget and sign off on school improvement plans.

At some schools, councils play an active role, meeting monthly, rallying families around issues and opportunities at campuses, and serving as a critical bridge between communities and schools.

But critics say many councils have been disempowered over the years by a lack of community involvement, poor training, and, at times, strained relationships with school leadership. Full councils are supposed to comprise the principal, six parents, two community members, two teachers, and one non-teacher staff member. (High school councils add a student representative.)

In the last round of elections, held in 2018, more than half of the Local School Councils across the city lacked enough candidates to fill each organization’s 12 seats. WBEZ reported this week that more than a fifth of the schools with police officers assigned to them don’t have school councils at all or fall short of having enough members to form a quorum, according to information obtained earlier in the year by the parent advocacy group Raise Your Hand Illinois.

Natasha Erskine, parent organizer with Raise Your Hand, said it wasn’t fair to place such a high-stakes decision on the groups. “Knowing there are school councils without a quorum, knowing there are schools with less empowered LSCs, it’s a bit disingenuous,” Erskine said. To strengthen the bodies, she suggested better training, and clearer rules to address occasionally strained relationships between councils and school leaders perhaps reluctant to share their authority.

The city’s teachers union also has been critical. Stacy Davis Gates, the union’s vice president, said that local school councils at low-performing schools can be stripped of their decision-making authority, with the result that any vote the groups make is purely advisory. Gates said this ties the hands of representatives at turnaround schools, which are disproportionately located in Black and Latino neighborhoods.

“Local school councils do not have the type of democracy that [Lightfoot] says that they do. And anyone who is a parent, anyone who has attended LSC meetings... knows that,” Gates said.

More transparency in voting

At Marshall Metropolitan High School in East Garfield Park, the council voted Tuesday to keep officers. Some parents wanted to closely watch the vote, since school officers were caught on camera last year dragging a student, whom they also tased, down the stairs in a high-profile incident.

The vote raised questions as to whether there were enough council members present to hold a legal vote or if proper notice of the meeting was given in accordance with Open Meetings Act rules.

Journalist Kelly Garcia submitted numerous requests asking Marshall Metropolitan High School’s administration and their Local School Council for meeting information. Meeting information on Marshall’s website was out of date, and Garcia got no response to her calls, emails, and Facebook messages asking when the vote would take place.

A parent eventually informed Garcia Tuesday morning that Principal Jammie T. Poole sent out the meeting details and video conference line at 8:35 a.m., less than 30 minutes before the meeting was set to take place.

When Garcia logged into the virtual meeting 20 minutes late, only five members of the Local School Council were present, not enough for a quorum according to CPS rules.

The council voted anyway. After Garcia joined, LSC members began expressing frustration that there was a member of the public on the call.

“Why are they here?” an LSC member asked, before someone motioned to adjourn the meeting. Garcia said members then discussed continuing the meeting at a later time in private.

The principal did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The council’s move to dismiss the public meeting because a reporter was on the line is concerning, said Maryam Judar, executive director of the Citizen Advocacy Center, a group dedicated to making the government more accountable.

“It’s a public meeting and reporters are members of the public and should have access,” she said.

Later, someone who answered the phone at the school and identified themselves as a local school council member said the vote was 9-0. That person refused to provide their name.

Chicago Public Schools officials did not provide a response to questions about the vote.

At Corliss High School in Pullman, representatives voted 8-1 to retain officers before asking parents and community members to comment, contrary to the rules asking schools to allow public comment first. The school did not say on its meeting agenda it planned to vote on the issue.

Principal Ali Muhammad told the group that the school has a good working relationship with its school resource officers.

“Those of you who know me know I’m not going to let anyone mistreat students,” Muhammad said.

Member Sheila Jones-Coleman said the officers went “beyond” to build relationships with students, even hosting an ice cream social.

Meanwhile, Cleopatra Watson, a council member and parent at the school, said she doesn’t think schools are a place for police.

Some votes taken before public comment, others delayed

At Prosser Career Academy in Belmont Cragin, the council on Wednesday changed its agenda at the last-minute, opting to make space for public comment before the planned vote on school police, rather than after.

The group, which had a quorum but no student member, ultimately tabled its vote, saying it wanted to survey students and consider results from a recent district survey.

At least 10 schools have decided to delay their votes.

One of those is Roberto Clemente High School in West Town, where the local school council met virtually last week to discuss the issue. In a rare advisory vote, the group voted 8-3 in favor of eliminating school resource officers. Two members were absent.

The vote was not binding, council secretary Daniel Marre said.

Principal Fernando Mojica said the group needed more input before formalizing the decision. “The purpose is not to just keep having votes. The LSC has already voted. We want to be able to engage stakeholders.”

The school is now planning two more community forums to review the issue, and it also plans to survey students. But some in the virtual public meeting questioned why the council was holding more meetings rather than sticking with the original vote.

A flurry of messages popped up in the virtual meeting chat box signaling that people were puzzled. “As a community member,” one person wrote, “[I] find this confusing.”

Freelance reporter Kelly Garcia and Chalkbeat Chicago intern Sneha Dey contributed to this story.