Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter.

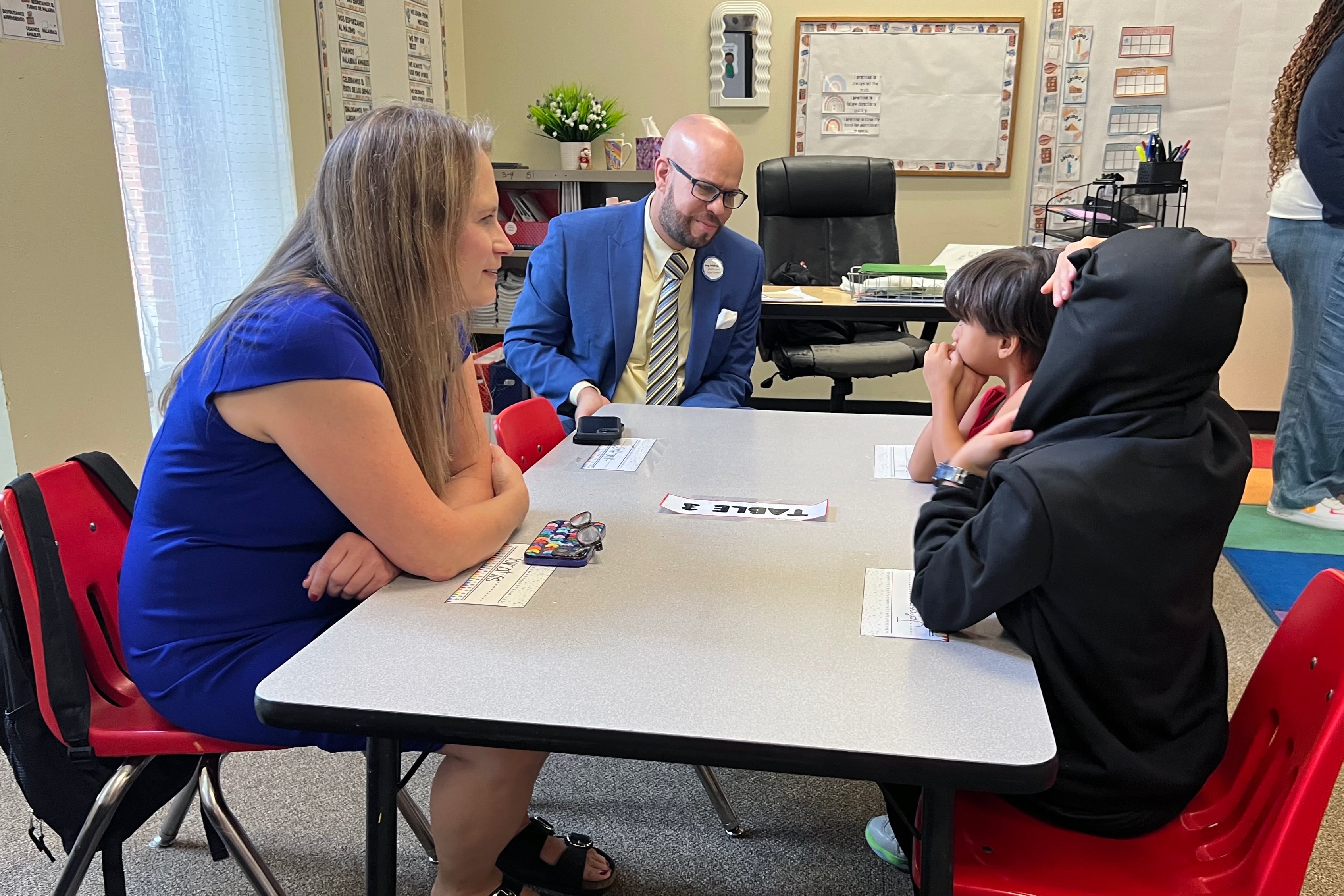

On the first day of school Monday, Denver Superintendent Alex Marrero sat on a wiggly stool no higher than his knee at a table with three young students. Wearing a pin on his suit jacket lapel that said “soy bilingüe” — “I am bilingual” — Marrero turned to the little boy next to him and asked in Spanish where he was from.

“I came from Venezuela,” the boy answered in Spanish.

“From Venezuela,” Marrero said. “How long have you been here?”

“Two months,” the boy said, swinging both of his legs as he spoke.

The boy is one of 22 students in a new combination kindergarten-first grade classroom at Wyatt Academy, a charter school in northeast Denver that narrowly escaped closure last school year. The closure attempt did not originate with Marrero or with Denver Public Schools, the district that has authorized Wyatt to operate as an independent charter school for the past 26 years.

Rather, it originated with Wyatt’s own board of directors. The Wyatt board attempted to close the charter school due to declining enrollment and per-pupil revenue. But after pushback from the Wyatt principal and a groundswell of support from families and community members, enough Wyatt board members voted against closure to keep the school open.

Part of Principal Melody Means’ plan to keep Wyatt open is a new partnership with ViVe Wellness, a nonprofit that has been serving some of the tens of thousands of migrants, many from Venezuela, who have arrived in Denver over the past few years.

Denver Public Schools enrolled more than 4,700 immigrant students over the course of the last school year, though not all of them stayed the entire year or are likely to return this year. The new arrivals helped stem years of declining enrollment in DPS, though officials anticipate the district will continue to lose more students than it gains and may have to close more schools.

For this year at least, the new kindergarten-first grade classroom at Wyatt helped boost the charter school’s enrollment to 239 students on the first day of school, a nearly 20% increase from last year.

As the teacher and aides helped the students line up to go outside — “walking, kids!” one repeated in Spanish in a sing-song voice — Marrero marveled at the program.

“To think this school was not going to be here this year,” he said.

Wyatt was one of several schools Marrero visited Monday with an entourage of district staff, cameramen documenting the day for social media, and school board members including President Carrie Olson and member Scott Esserman.

He kicked off the day at Polaris Elementary, a magnet school for students identified as gifted and talented, before visiting Park Hill Elementary and University Prep Steele St., a charter elementary school. After Wyatt, he headed to Garden Place Academy, GALS Denver, which is a charter middle and high school, and then Dora Moore ECE-8.

At Garden Place, Principal Andrea Rentería gave Marrero a tour of the school. Garden Place, in north Denver, has both a Montessori program and a bilingual program for Spanish-speaking students. It was one of many DPS schools that enrolled newly arrived students last year from Venezuela and other South American countries.

Marrero wandered into a third grade bilingual classroom and sat down next to a little girl in a pink shirt patterned with butterflies. As the teacher gave directions in Spanish, Marrero took the magnetic pin off his lapel and leaned toward the girl, encouraging her to sound out the words.

“Soy,” Marrero said.

“Soy,” the girl repeated.

“Biiii —” he said, waiting for her to repeat the sound. “Bilingüe.”

“Soy bilingüe,” the girl said.

Marrero then affixed the pin to the girl’s shirt.

Melanie Asmar is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Colorado. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org .