When the coronavirus shut down Michigan schools in March, Stacey Young tried to shepherd her five children through online classes at home while continuing to work remotely herself.

The Youngs lasted until mid-May before calling it quits more than a month before classes ended.

“I felt bad, but I was like, ‘We’re done with it,’” Young said. “One son, who does very well in school, he was overwhelmed. He said, ‘I don’t want to sit on the [video] calls.’”

The family is again absent from the Detroit Public Schools Community District this fall, but they are back to learning. Young decided to home-school her children rather than attempt another semester of classes by videoconference.

The Youngs are among the estimated tens of thousands of Michigan students who didn’t return to school as expected this fall. As school officials try to account for those students, they say a sharp increase in home schooling helps explain some of the decline.

Growth in home schooling during the pandemic underscores the dilemma facing many families in Michigan, especially low-income families who are less likely to have an in-person learning option. Even as they struggle mightily with online learning, few are willing to send their children to school in person due to concerns about the coronavirus.

The number of registered home schools in Michigan more than doubled this fall, jumping from 290 to 611. That’s a tiny sliver of Michigan’s 1.5 million public school students, but it’s likely an undercount because parents don’t have to inform anyone when they decide to home-school their children. Officials say the numbers may represent the overall trend in home schooling, even if they don’t reflect the total number of home schools in Michigan.

Some parents say home-schooling is the best option available to them during the pandemic. But while higher income families are able to work from home or take time off to home-school, many families don’t have that choice. Some low-income families, such as the Youngs, have found grants to cover home-school costs. But home schooling likely isn’t an option for parents who work in person, or who rely on their school for disability services, or who can’t cover the costs of school materials.

Even if home schooling were an option for every family, educators worry that students will fall even further behind while they work from home. Research suggests that home-schooled children do as well as their public-schooled peers in college, but there’s little precedent for pandemic-era home schooling. What’s more, most home schools in the U.S. have typically been run by stay-at-home mothers, an option that is not available to many working class people during the pandemic.

“I do believe that they will come back, and when they do I’m concerned about needs they will have all at once when the return occurs,” Erik Edoff, superintendent of L’Anse Creuse Schools in suburban Detroit, said of home-schooled students. He said the district, which enrolls roughly 10,000 students, audited its fall enrollment and found the numbers declined roughly 2.5%, often because families chose to home-school.

Indeed, national polls and data from other states point to upticks in home schooling nationwide.

“I lend significant credence to the doubling,” said State Superintendent Michael Rice. He added that the overall number of home-schooling families is likely small, and that home schools likely don’t come close to accounting for all of the students who didn’t enroll in school this fall.

Interest in home schooling has exploded during the pandemic, said Chandra Mongtomery Nicol, executive director of the Clonlara School, an Ann Arbor-based private school that for decades has offered support to home schools.

“Our phone rang off the hook all summer with people interested in online school and homeschooling,” she said.

Enrollment declines during the pandemic — and the rise of home schooling in particular — raise a number of thorny policy questions. For instance, Rice would like to see a statewide count of home-schooled students, an issue that has been hotly debated in Michigan for decades. And superintendents say they stand to lose critical state funds due to declining enrollment, although the latest Michigan budget partially shields them from pandemic fluctuations this year.

But those policy questions hardly register with families who are dissatisfied with online education.

“I knew when this virtual thing started that there would be some kinks, and I wanted to give it time,” said Jeanetta Riley, a single parent whose daughter is a ninth grader in Detroit. The family meets the low-income threshold for the federal lunch program.

“It just felt like in the beginning, she wasn’t learning anything. But then the weeks kept going, and she’s still not learning anything. The kids are in breakout rooms, the teachers aren’t in there, and the kids are doing whatever they want. It was just unorganized, a lot of chaos.”

Riley had heard from a friend that a group of families was forming a home-schooling pod. The group’s leader, Bernita Bradley, is a midwest delegate to the National Parents Union. The advocacy group is backed by the Walton Family Foundation (a Chalkbeat funder). She secured a $25,000 grant from the group to help families home-school during the pandemic.

The idea of home-schooling appealed to Riley, and she had time to spare after being laid off from her job at the Fiat Chrysler plant in Detroit. But she doubted her teaching ability. “I was very scared,” she said.

Riley noted that she likely wouldn’t have had the confidence to begin home-schooling her daughter if not for the coaching she received through the grant.

“It’s not easy at all, but having this group’s support has made it a lot better,” she said.

Riley says home schooling would be an option for more families if schools provided supplies and curriculum that might not otherwise be affordable.

Stacey Young agrees that home schooling would have been much more difficult without the extra help she received through grants.

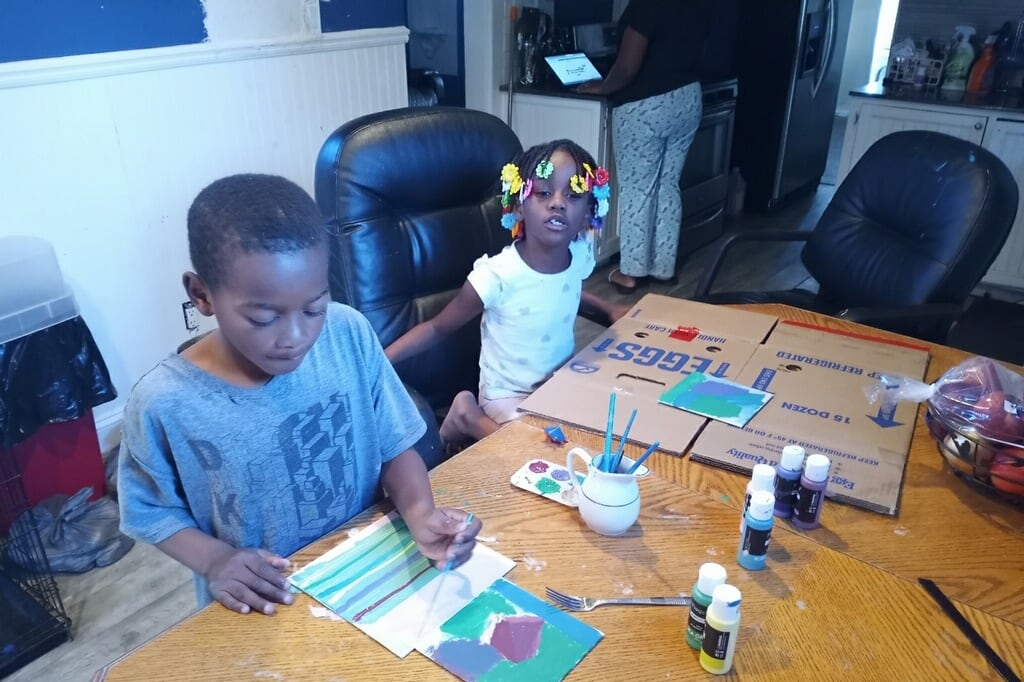

“It’s a huge help,” Young said, pointing to coaching, art supplies, and desks that she received through the home-school grants. She says she isn’t sure yet whether she will continue home-schooling her five children after the threat of the coronavirus fades.

Even if they eventually return to school, she says they are better off now than they were when they were learning online. The family didn’t have enough computers or work areas for everyone, and the children rebelled against virtual lessons.

“They were sulking,” she said. “They would disappear. My son would come upstairs and hide under his bed. My other son, the one who really enjoys school, is like ‘Mom, I’m not feeling it.’ That’s what he told me. He’s 7.”

Now the children learn on their own schedules, making it easier to share space and computers. The family has taken lessons in music and cooking through online programs provided by their home school grant, and have spent time talking about Detroit’s past with a local historian. The eighth and tenth graders work on their math skills online, while Young works with the younger children.

Still, Young acknowledges that her children are missing out on some of the services they would normally receive through school. One of her sons typically receives speech therapy at school. He hasn’t been getting it at home, though Young is researching whether her insurance will cover the therapy.

She decided not to petition the school for special education services for her son, which she figured would turn into a prolonged bureaucratic battle.

“I feel like we need to just step out of [the district],” she said. “You know, while they figure stuff out.”