Back-to-school legislation that gives Michigan schools a choice between online and in-person instruction but requires them to review their decisions continually is headed to Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s desk as classrooms begin reopening across the state.

Whitmer is expected to sign the package of three bills, which passed the state House on Monday with support from leaders of both parties.

The legislation represents a compromise after months of wrangling over whether — and how — schools should reopen. Schools won’t be required to provide in-person instruction to students in grades K-5, as an initial Republican proposal stipulated. But attendance will be taken, and school funding for the year will depend in part on how many students show up this fall, measures that many Democrats opposed.

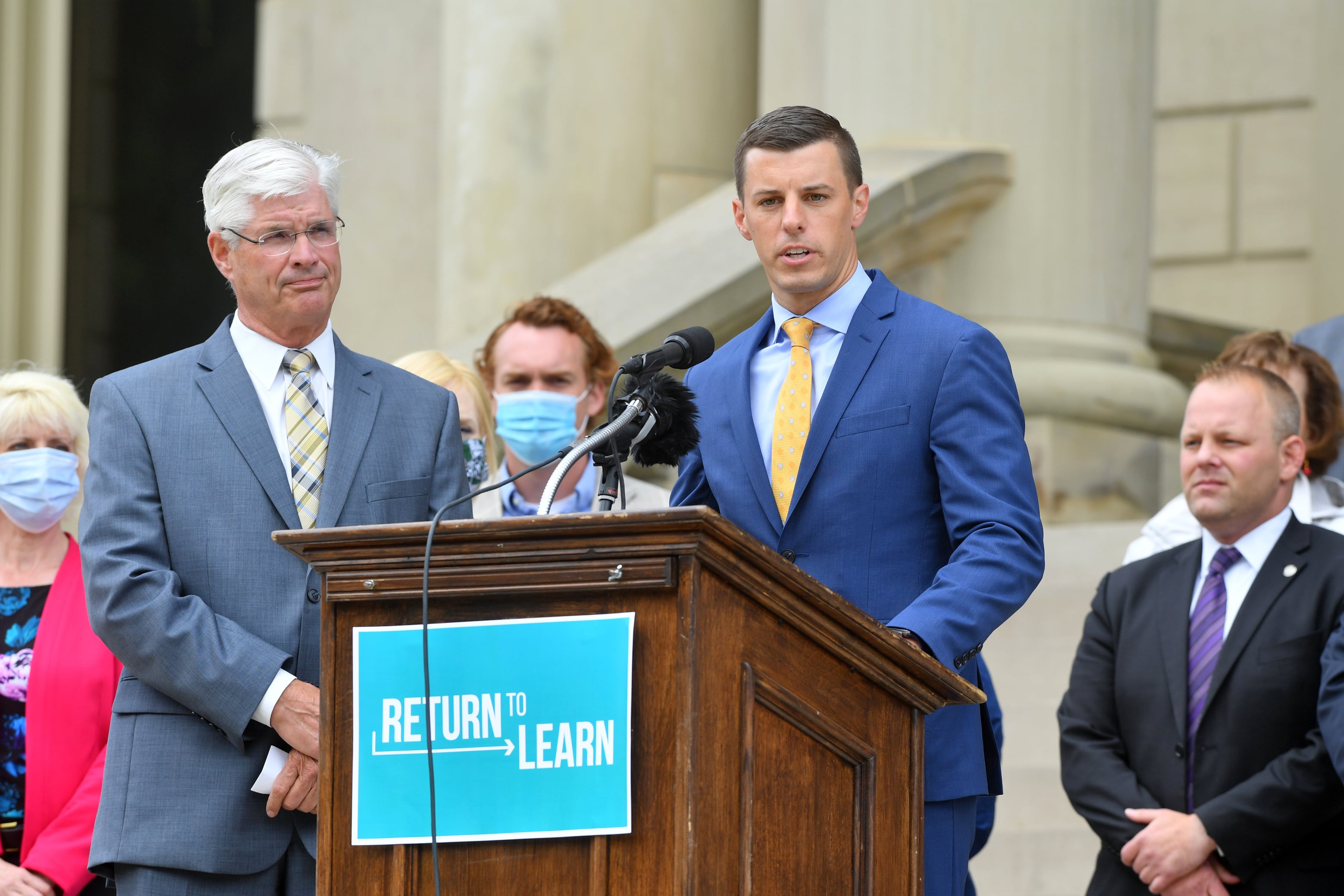

“What we’re doing today is a true testament of what can happen when we work together,” said Rep. Lee Chatfield, the Republican speaker of the state House. “Educating our kids should not be partisan.”

The Senate passed the measures on Saturday after Whitmer and top GOP lawmakers ironed out an agreement on Friday night. The bills do not provide clarity on how much money schools will get this year, as the coronavirus-induced recession has depleted state coffers.

Still, school leaders now have a resolution to some key issues:

- Online instruction will be counted as equivalent to in-person instruction during the pandemic.

- The enrollment counts for 2020-21 that determine state funding will be a combination of last year’s enrollment count (weighted at 75%) and this year’s count (weighted at 25%).

- Schools will be required to administer benchmark tests to students and report the results to the state. However, the scores won’t be factored in the state’s school accountability system.

- Districts will be required to develop another round of coronavirus learning plans by Oct.1, which must be passed by local boards of education and renewed by local boards every month.

Rep. Lori Stone, a Democrat on the House Education Committee, voted in favor of the bills. She said that she didn’t like all aspects of the compromise, but that her reservations were outweighed by schools’ need for clarity.

“It is unreasonable to ask school districts to balance an equation with so many variables,” she said. “It is time that the Legislature does our part.”

The state’s two largest teachers unions backed the package, as did other top Democrats.

Some in the party voted against the measures. The bills require school boards to reconsider their approach to learning every month during the pandemic, which Rep. Leslie Love called an “undue burden.”

Rep. Darrin Camilleri, a Democrat who voted against the new attendance rules, said schools should not be penalized if teachers don’t have at least one two-way interaction with each of their students every month.

“We are likely to see great fluctuations in daily attendance because of the pandemic,” he said. “Let’s hold our schools harmless.”