Karlotta Hicks was ready to teach online. Her handmade Zoom background featured numbers and the ABCs, kindergarten concepts she hoped would jog her first graders’ memories after nearly six months away from the classroom. She’d spoken by phone over the summer to the parents of her 14 students, letting them know that virtual classes would begin right after Labor Day at 8 a.m.

“It’s going to be as if the kids were in front of me,” she said confidently a week before classes began at Winans Academy for Performing Arts.

When class began on Tuesday, just one student appeared in her virtual classroom, and his audio wasn’t working. Across the country, hundreds of thousands of students and teachers were troubleshooting their way through glitch-filled first days of online learning. This was going to be tough.

After a spring of incalculable loss, educators in Detroit are scrambling to get students back on track. As the pandemic continues to spin out of control, schools have been forced to choose — with little guidance — from a menu of bad options for resuming classes. Winans Academy, set in east Detroit neighborhoods that bore the brunt of the coronavirus pandemic, chose to begin the year entirely online.

This spring, as the virus snowballed in Detroit and the city’s unemployment rate spiked to historic levels, school fell by the wayside for many families. Fewer than half of the students checked in with their teachers in an average week.

“Parents told me, ‘on the scale of things I’m dealing with, school work is No. 5,’” Principal James Spruill said.

Many students at Winans had fallen behind even before the pandemic. The school’s growth scores, which measure student improvement on standardized tests, have remained stubbornly low despite repeated staff shake-ups and state interventions. Experts warn that the pandemic will likely make things worse at schools like Winans, where nearly every student is economically disadvantaged.

The stakes have never been higher for the latest reinvention effort at Winans Academy. After surveying teachers and staff, school leaders announced that classes would be held online until January at least.

Would virtual instruction — a new format for most school staff — allow students to catch up, or at least avoid more backsliding?

Would students even show up?

“Give me a thumbs up if you can hear me,” Hicks said to her lone student. He wore bright blue headphones printed with characters from the movie Toy Story 4. No thumbs up.

Eventually, his mother leaned over the tablet that the school had lent the family, and the audio crackled to life.

“Yay, it’s fixed, wonderful,” Hicks said. “Welcome to the first day of school.”

At 8:12 a.m. Hicks decided to stick with her game plan. She cued up a welcome song she’d found online. She sang along to the video: “Good morning, good morning, how are you?” The student smiled and mouthed some of the words, but the sound was choppy.

“Could you hear me singing when it glitched?” she asked.

“I didn’t hear you because of the glitching,” he said.

“You didn’t hear me, oh my goodness. I was singing, I was going all in!”

“Sorry.”

“No worries,” she said. But she decided to reschedule class for 12:15 p.m.

“I’m going to do the introduction with everyone,” she told the student’s mother. “I just need to call them to see where they are.”

‘I can easily say 100’

On a sunny Wednesday afternoon a week before classes began, it seemed like the entire neighborhood around Winans had gathered at the school to pick up devices and school supplies. Enrollment had been trending down for years, but more than 300 parents had already signed up, and Spruill estimated that at least that many came by. A line of cars snaked around the block.

Near the front door, teachers piled up backpacks stuffed with workbooks, pencils, and other school supplies. Wearing masks and keeping their distance, families and teachers greeted each other as if they hadn’t been together in years.

Lynn Coleman, a middle school math teacher, found one of her top students from the previous year. “Guess who got into Renaissance?” she asked school staff, referring to the selective Detroit high school.

“She worked us hard enough,” the student said, smiling.

Coleman grew up not far from Winans, attending nearby Denby High School, and she takes pride in the easy connections she makes with students.

Those connections took on a painful weight this spring: The coronavirus death rate in the school’s ZIP code, 48224, and in surrounding ZIP codes is more than three times higher than the death rate across Michigan. Coleman says the virus spread rapidly through her large extended family this spring, sickening eight people and killing several.

“I can easily say about 100” friends, family, and acquaintances got sick, she said. “Easily.” Her great aunt and uncle, who had been married for 60 years, died within a week of each other.

“If we are going through that, who knows what our scholars are going through?” she said.

Early in the pandemic, one of her students called her cell phone at 9:30 p.m.

“She said, ‘Miss Coleman?’ I said ‘Yes?’ She said, ‘Oh, I miss you.’” The student got off the phone quickly, but Coleman sensed the call’s significance.

“She only knows what that may have done for her,” Coleman said.

‘Where are the kids?’

Even after the community endured so much grief, the first day of Coleman’s math class felt almost normal.

Her goal for the day was to establish norms for virtual learning and to get to know her students by asking them about their summers, but the kids were playing it middle-school-cool.

“I didn’t do nothing this summer but sleep,” said one student. “I did order some shoes.”

“I didn’t do anything but be in my room on my phone,” another said.

“Were you playing on TikTok?” Coleman asked, referring to the video-sharing app.

That got a surprised laugh.

“Yeah, I know about TikTok,” she said.

They got through the rest of the lesson OK — students agreed that they should mute their microphones while others were talking and refrain from making fun of each other for incorrect answers — but there was a problem: Only nine students showed up of the 25 she was expecting.

Teachers across the school were reporting the same issue. While the school didn’t confirm the actual attendance number, Spruill acknowledged that attendance was low.

“The teachers and I were kind of sad at one point today,” Hicks said. “Like, where are the kids? It was emotional, because we weren’t having that interaction with our students, and that’s what you long for as a teacher. We just had to pull ourselves together, because we can’t let the kids see us like that.”

Hicks got some answers after calling families who had missed her morning class. One family had lost power during a morning thunderstorm that cut power to 4,000 Detroit homes, many of them near Winans. Other families were struggling to log onto their new laptops.

Spruill, who previously worked as a technical consultant for other charter schools in Detroit and who is the primary tech support person for Winans Academy, said he was not surprised by the low turnout.

“It was a constant line of parents not knowing how to log in,” he said. He insisted that attendance will improve throughout the week, adding that many schools in Detroit see attendance fluctuate wildly in the first weeks of school, because parents often sign their children up for more than one school.

Still, a more troubling possibility loomed: What if virtual learning asked too much of families, many of whom had jobs or were looking for one, and didn’t have time to provide full-time academic support for their children?

The phone numbers for three families in Hicks’ class were disconnected — what would happen to those students? And many parents already seemed stretched thin.

“I’m bouncing around to help my other kids,” one parent told Hicks. “I’m here, but I might not be on the screen.”

Amber White, whose son is a first grader in a different class at Winans, said she spent an hour on Tuesday morning just getting her two children logged on.

“This morning, it was really, really rough,” she said. “I was like ‘no, this isn’t going to work.’”

White took a week off work to help her kids get acclimated, but she worries that she’ll need more time. She was among a minority of parents at Winans who said they wanted the school to provide some in-person instruction this fall, and she said the first day of school showed that she was right.

“I mean, I understand the danger,” she said. “But the reality is that y’all might need to open the schools.”

‘We just have to make it work’

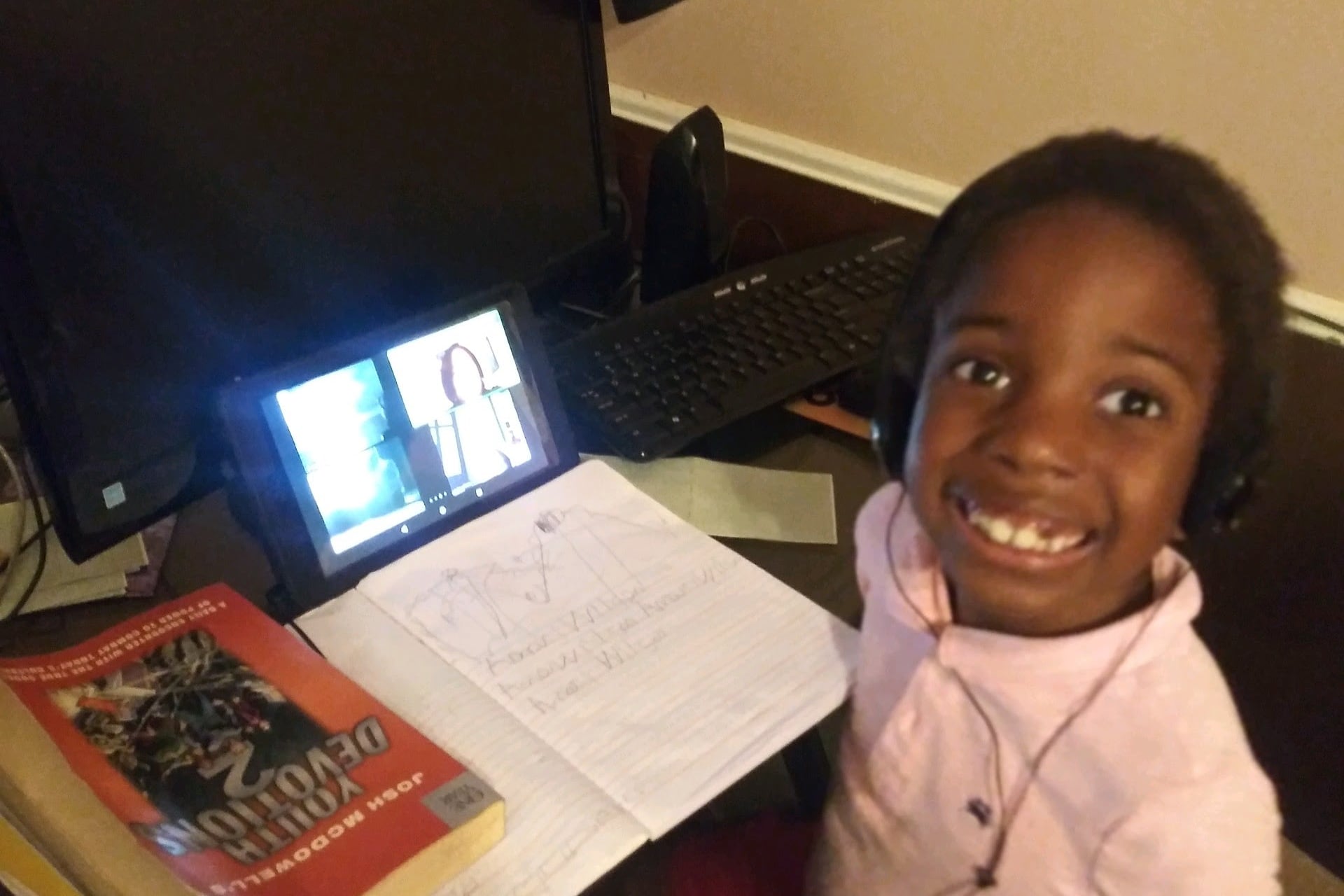

By 12:15 p.m., Hicks could breathe a small sigh of relief. Seven students popped into her Zoom class — just half of the total, but much better than one.

Hicks had the students practice what would become their morning routine, starting with the Pledge of Allegiance, then ran through class rules.

The students were visibly delighted to be in class together, virtual or not. They called out each other’s names and pushed their faces right into the camera. One girl wore a T-shirt printed with the words “First Day of Distance Learning 2020.”

“What did you learn today?” Hicks asked.

“Today I learned that school is fun,” said the boy with the Toy Story headphones.

“That makes me smile, my heart is smiling,” Hicks said.

The last part of the first day featured a story. A classroom aide read aloud as Hicks stepped away to take a phone call from a parent. The book, called “I Love School,” traced the routine of a single fictional school day. The pictures showed scenes that must have felt very distant to 6-year-olds who hadn’t been inside a classroom since March: a teacher leaning over students’ desks to look at their work, students eating lunch together in a cafeteria, students sitting in a circle on a rug while their teacher read a story aloud.

“Tell me what the story was all about,” the aide asked when it was over.

“I liked it because it told us about school, and we haven’t been at school for a loooong time,” said a girl with no front teeth and black beads in her braids.

“I miss my school,” said another student.

“And we miss you guys, but it’s so good to see you here now,” said Hicks, sitting back down. “This is our new way of going to school.”

That won’t change until January at the earliest. Winans officials said that they’ll consider moving to a hybrid schedule, bringing students into classrooms in shifts, if local coronavirus metrics take a turn for the better.

Facing nearly four months of online teaching, Hicks says she remains optimistic.

“It’s just Day One,” she said. “Seven came in, and they’re excited. That’s what you want, especially at this age, is for them to want to learn. That’s how you create lifelong learners. I’m excited for that.”

“It’s not like there are other alternatives,” she added. “This is how learning is occurring. We just have to make it work.”

This story is part of a series examining how Detroit schools, including Winans Academy, are adapting to educating students in the pandemic.