There’s a lot Azaria Terrell wants to tell adults about how they can help students who, like her, have experienced homelessness. She’d start with a few simple tips: Listen to them, develop relationships with them, and give them some grace.

Too often, she said, school staff place too much academic pressure on students who are homeless.

“Making sure I’m OK and getting a good night’s sleep … that’s way more important than making sure I’m turning in my assignments,” said Azaria, who is 17 and a senior at Pershing High School in Detroit.

“At the end of the day you can go home and lay in your bed and maybe grade students’ work, but that child has to stay on the streets that night. Not everybody is lucky enough to have friends to go stay with or family to go stay with. Sometimes they’re in abusive households and they literally have nowhere else to go. So, patience is really key.”

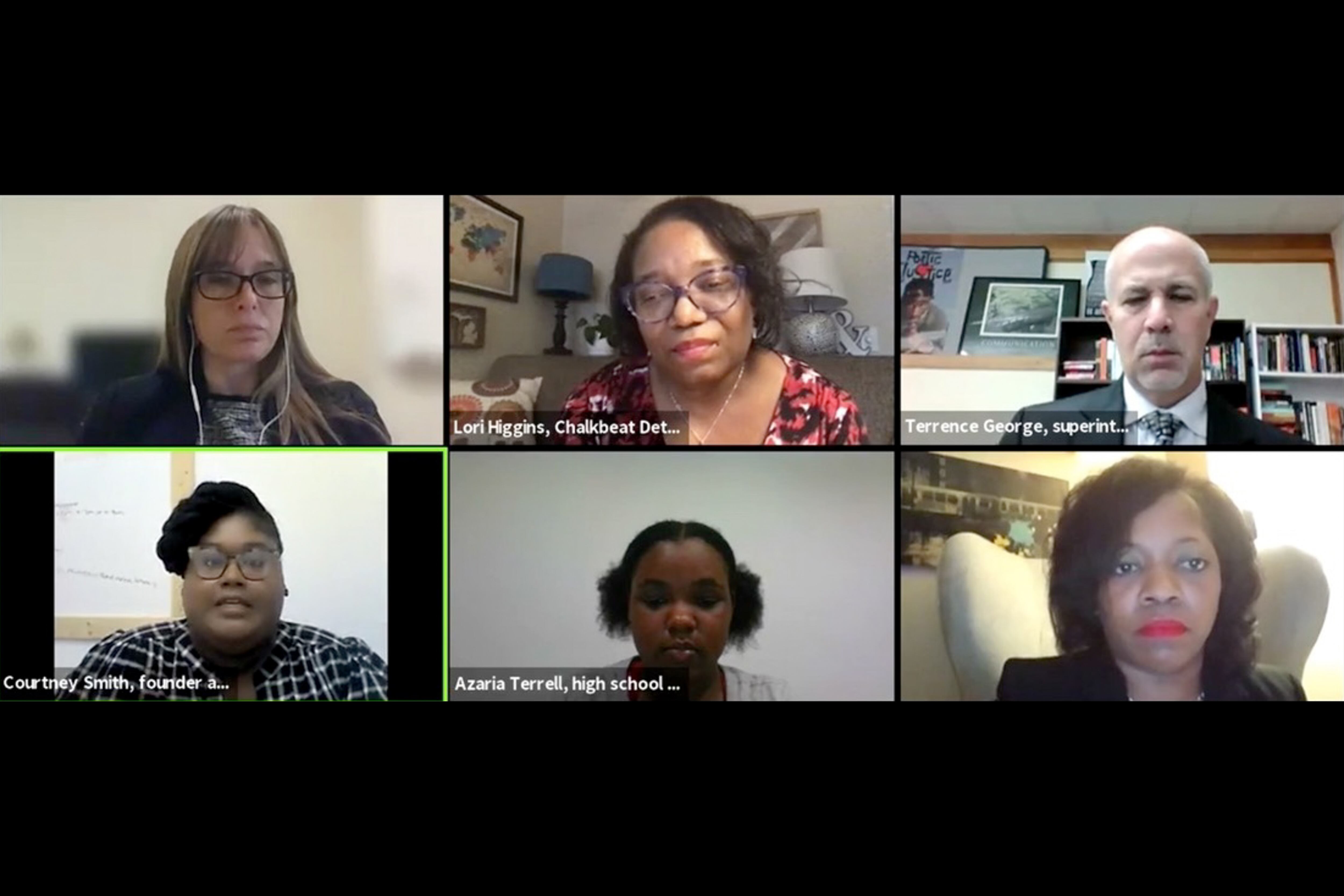

Azaria, who has experienced homelessness during her high school years, shared her story during a panel discussion Tuesday co-hosted by Chalkbeat Detroit and the University of Michigan Poverty Solutions (Watch the conversation in full at the bottom of this story).

The discussion was held in the wake of new research that shows schools in Detroit are struggling to identify students who are homeless and entitled to federally required services, such as transportation.

Azaria was joined on the panel by representatives of local schools, a researcher, and the founder of a Detroit nonprofit that works with young people like Azaria.

Here’s who joined her on the panel, and a snippet of what they had to say.

- Jennifer Erb-Downward, senior research associate at Poverty Solutions at the University of Michigan, an initiative that partners with communities and policymakers to prevent and alleviate poverty. Erb-Downward explained that the federal definition of a homeless student is any child who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence. That includes children living in shelters or on the streets, but it also includes students living temporarily in a motel or hotel as well as children living doubled up in another person’s home because of economic hardship. “The reason that definition is important to focus on is that what the research shows is that from an educational perspective, it’s really the instability that children are experiencing that has educational consequences,” Erb-Downward said.

- Courtney Smith, founder and CEO of the Detroit Phoenix Center, which provides services to homeless students. Smith said the center began as a drop-in center for students to hang out, take a shower, wash their clothes, access a food pantry, get bus tickets, and participate in recreational activities. Now, there is also an after-school program that provides tutoring and other services, such as counseling. Smith said the programming was built around what students said they needed. Listening to their wants and needs was important, she said. Adults “often create programs without young people being at the table.”

- Iranetta Wright, deputy superintendent of schools at Detroit Public Schools Community District, which has expanded its services to better identify and serve students who are homeless. In 2017, when the district’s current administration took the helm, there were only 600 students — out of about 47,000 — identified as homeless. There was no doubt that number was too low, she said. So the district revamped its efforts, ensuring every school identified someone to serve homeless students, and provided staff training. At the end of the 2020-21 school year, the number of identified students had grown to 1,900. Training has been an important part of helping staff understand what it means to be a homeless student, and also how to talk to students who confide in them. “Awareness is important for everyone, from our teachers to our custodians to our cafeteria workers, to our noon hour assistants. Everyone needs to be empowered with the right language,” Wright said.

- Terrence George, superintendent at Covenant House Academies, which were founded to help at-risk students obtain their high school diplomas. The academies especially help those living in shelters operated by Covenant House, which the school is affiliated with. “Homelessness isn’t always about staying in a shelter. It can be bouncing around. We have so many kids in our school that couch surf. It’s … now not where do you live, but where are you staying tonight is the question,” George said. The school provides a range of services, and is working to ensure all of its three locations have showers, laundry machines, and close access to a child care facility.

The event began with a documentary clip currently being produced by Sofa Stories Detroit, a community arts program that uses live performance and theater to tell the stories of Detroit youth who have experienced homelessness and housing insecurity. The name of the production company acknowledges that for many youth, surfing on the couches of friends or relatives is common. The full film will be streamed live in November, during National Homeless Youth Awareness Month, said Andrew Morton, director of the project. Find more information here.

Azaria, the Pershing High student, said identifying students who are homeless isn’t always easy. Educators can look out for students who repeatedly wear the same outfits, or students who start secluding themselves from others, she said. But many homeless youth become good at hiding their struggles.

“They’re hiding it not only from the world, but from themselves. They’re trying to erase that part of themselves and build a new character at school so they’re not judged, so they’re not looked at wrongly, so that their family isn’t criticized.”

It’s something Azaria knows really well. She said she’s a different person at school, known there as someone on the right track and on her way to college. At home, she said, she could be struggling. She cited her connection with Smith and the Detroit Phoenix Center with giving her a voice to tell her story. Smith, she said, was “the kindest person” she’d ever met.

“I meet a lot of kind people who really only want to hear your story to benefit them. And that’s sad. Ms. Courtney — she’s kind. She really listened to me. She gave me opportunities to use my voice.”

She wants teachers and other school staff to care not just about how students are doing academically, but how they’re doing outside school. She said they need to “dig deeper, build a relationship with their students, and really see how their life is going.”