The Detroit school district is boosting the pay of security guards to address a severe shortage that has left some buildings with fewer guards and raised concerns about school safety.

“We will continue to hire, and we will continue to negotiate higher wages, at least for the employees who work for us,” said Superintendent Nikolai Vitti in a recent school board meeting.

The security guard issue is top of mind in the Detroit Public Schools Community District, where school safety is usually one of the top considerations of parents when choosing schools.

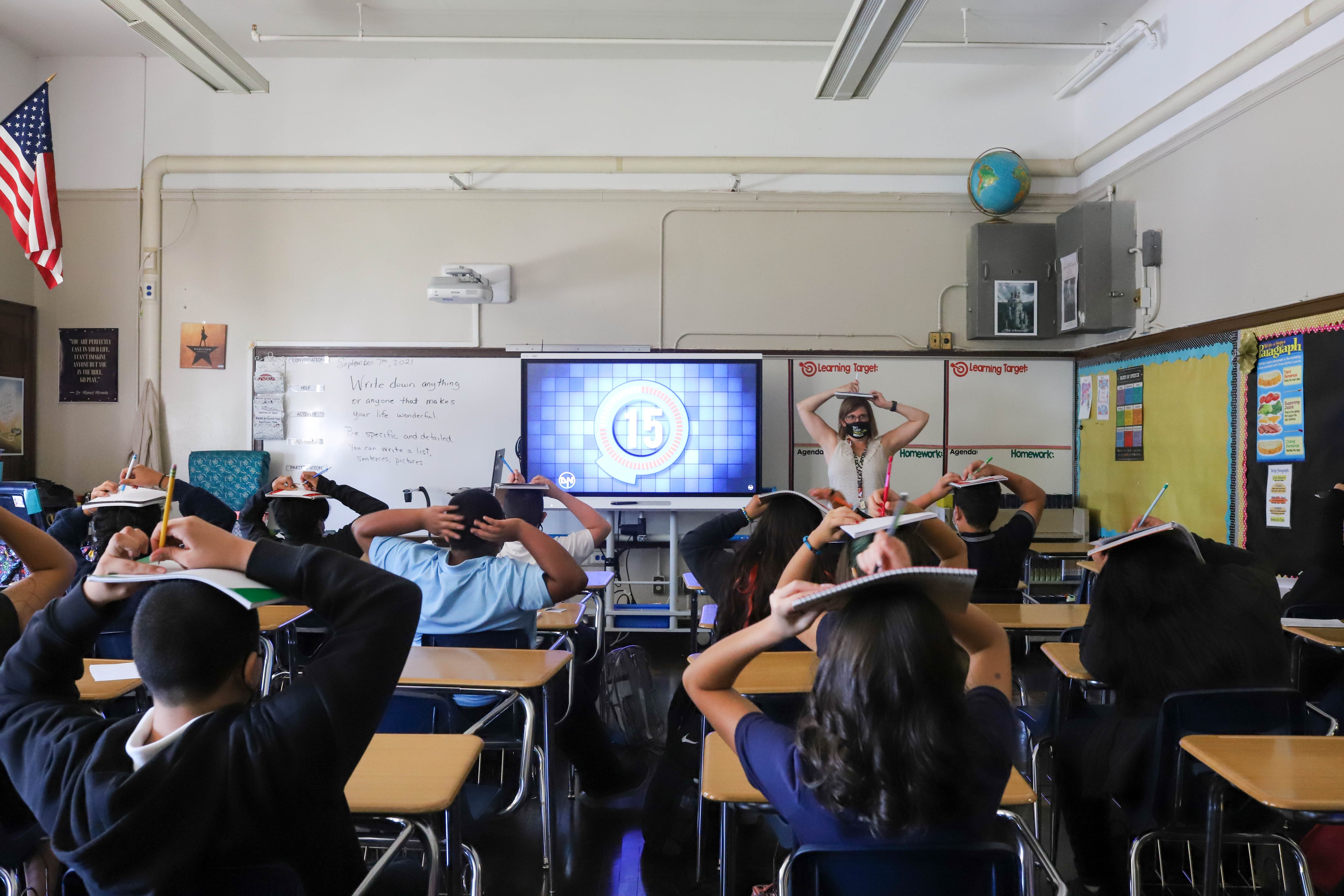

The shortage has been exacerbated in part by the pandemic, when the district needed fewer security guards because fewer students were in buildings. But now, as most students and teachers return to in-person learning, the Detroit school district faces many of the same difficulties the private sector faces trying to find hourly employees.

To address the shortage, the district is working to hire 40 security guards, and has been moving guards from schools with fewer safety issues to schools with more. Prior to the pandemic, most high schools employed two to three security guards.

The district did not respond to Chalkbeat’s request for the current number of security guards in schools.

Multiple educators, both during a school board meeting Tuesday and on social media, expressed concern about the dwindling number of security personnel at some schools as well as the stress of handling fights themselves.

N’shan Robinson, lead counselor at Mumford High School, told the board that she intervened in a fight that took place outside the school. She added that a lack of substitute teachers and security have placed a heavy burden on educators.

“I am a school counselor. I should not have to put my life on the line to help a staff member who’s probably getting beat up,” Robinson said.

Charlotte Smith, an English teacher at Cody High School, said she and other teachers would feel safer if there were full-time security guards to ensure outside strangers cannot roam the halls.

“We’re not asking them to run and break up fights, not arresting kids, we’re not looking for that. We’re just looking for someone at the front door to check people in and make sure that we are safe.”

At Tuesday’s meeting, Vitti explained that every high school would be assigned a security guard, a campus police officer, or both.

Security guards differ from campus police officers, who are trained to work in schools with students. Security guards are tasked with monitoring the front desk at high schools as well as clearing hallways and maintaining order.

“We will commit to having more security guards in schools with a large number of students,” Vitti said.

Among the factors that will determine the number of security guards in a school includes the number of students, the number of reported incidents, and the building’s layout.

Smaller elementary schools have opted to hire neighborhood parents as “greeters” to meet students at the front door and direct parents or guardians to the main office.

Board members expressed their concern over the shortage, particularly the district’s salary for security guards.

Prior to the pandemic, the hourly wage for security guards was $12.61 per hour, Vitti said. The district raised it to $15 per hour this fall.

“I know in fast food you can make more than $15 an hour. So it is going to be extremely difficult to fill those positions,” board president Angelique Peterson-Mayberry.

“We want to make sure that parents feel that their children are safe when they drop them off at schools.”