Tens of thousands more Michigan families soon will have access to subsidized child care. In parts of the state where child care is in short supply, new funds will help open new centers. Existing centers, many of which struggled to stay open during the pandemic, also will get an infusion of stabilization funds.

Those are just a few features of a $1.4 billion investment in Michigan’s child care system. The new state budget, which draws heavily on federal COVID aid dollars, is expected to have an immediate impact on families with young children, and to close funding gaps in the early education system that have destabilized the early childhood workforce and left wide swathes of the state in “child care deserts.”

“This is a huge step in the right direction,” said Matt Gillard, president of nonprofit advocacy group Michigan’s Children. “The need for investment in our public child care systems is clearly being seen.”

The budget passed the GOP-led legislature on Wednesday with bipartisan support. While Michigan’s multi-billion dollar budget surplus meant there were fewer tough spending decisions to make, advocates also noted that the state’s child care programs have long enjoyed bipartisan support. Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, a Democrat, said in a statement that she plans to sign the bill, which would go into effect Oct. 1.

Business groups have thrown their political weight behind expanded child care programs, arguing that affordable care frees more adults to enter the workforce. Parents — especially women — stopped working in large numbers during the pandemic, in part because of a lack of affordable child care.

Up to 105,000 additional Michigan children will be eligible for child care subsidies under the proposed budget. That’s more than a threefold increase.

Child care measures included in the budget proposal include:

- $700 million in stabilization grants, which will go directly to child care providers to cover costs and help them stay open.

- $108 million to increase income eligibility for the child care subsidy program to 185% of the poverty level from 150% through fall 2023, after which it will drop to 160% of poverty.

- $36.5 million to contract with providers who care for infants and toddlers. Care for the youngest children is in short supply, in part because it is expensive — an adult can only legally care for 3 or 4 infants at a time. Through contracts — as opposed to biweekly reimbursement — the state can provide more stable funding.

- $100 million to help open new child care centers in areas where there aren’t enough early childhood classrooms and to expand existing centers.

- $158 million to increase reimbursement rates by 30% for providers who participate in the child care subsidy program.

- $222 million to further boost reimbursement rates on a temporary basis. Rates will increase an additional 50% for 6 months, 40% for the next 6 months, and 30% until the funds are used up.

- $30 million to pay child care workers a $1,000 bonus.

Education advocates say that high-quality, intensive early education has a lasting positive impact on a child’s life, strengthening their performance in school and reducing odds that they will struggle with substance abuse.

The new budget pours $1.4 billion into Michigan’s largest child care program, Child Development and Care, a system of subsidies that cover private care for low-income families. It comes after the state expanded a separate child care program, Great Start Readiness Program, a state-run free preschool for 4-year-olds from low-income families.

“This is going to be a tremendous investment in supply and demand sides,” said Dawne Bell, executive director of Early Childhood Investment Corporation, a Michigan nonprofit that works with the state on early childhood issues.

Bell noted that much of the new funding will expire within three years, and that several key changes to the child care subsidies — including the expanded eligibility — come with expiration dates.

“Yesterday’s budget deal is historic, and yet we deeply hope that this is a down payment on continued investment in our youngest children,” she said. “COVID-19 has brought into focus how critical and essential child care is to the state’s economy and to future generations and to working families.”

Once the budget is passed, state officials will face a tight timeline to distribute hundreds of millions of dollars. They have just three months to distribute $700 million in stabilization grants, which are intended to cover operating costs and help keep child care centers open. Michigan has lost 6% of its child care providers during the pandemic, according to data from the Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs, though Bell said that is likely an undercount.

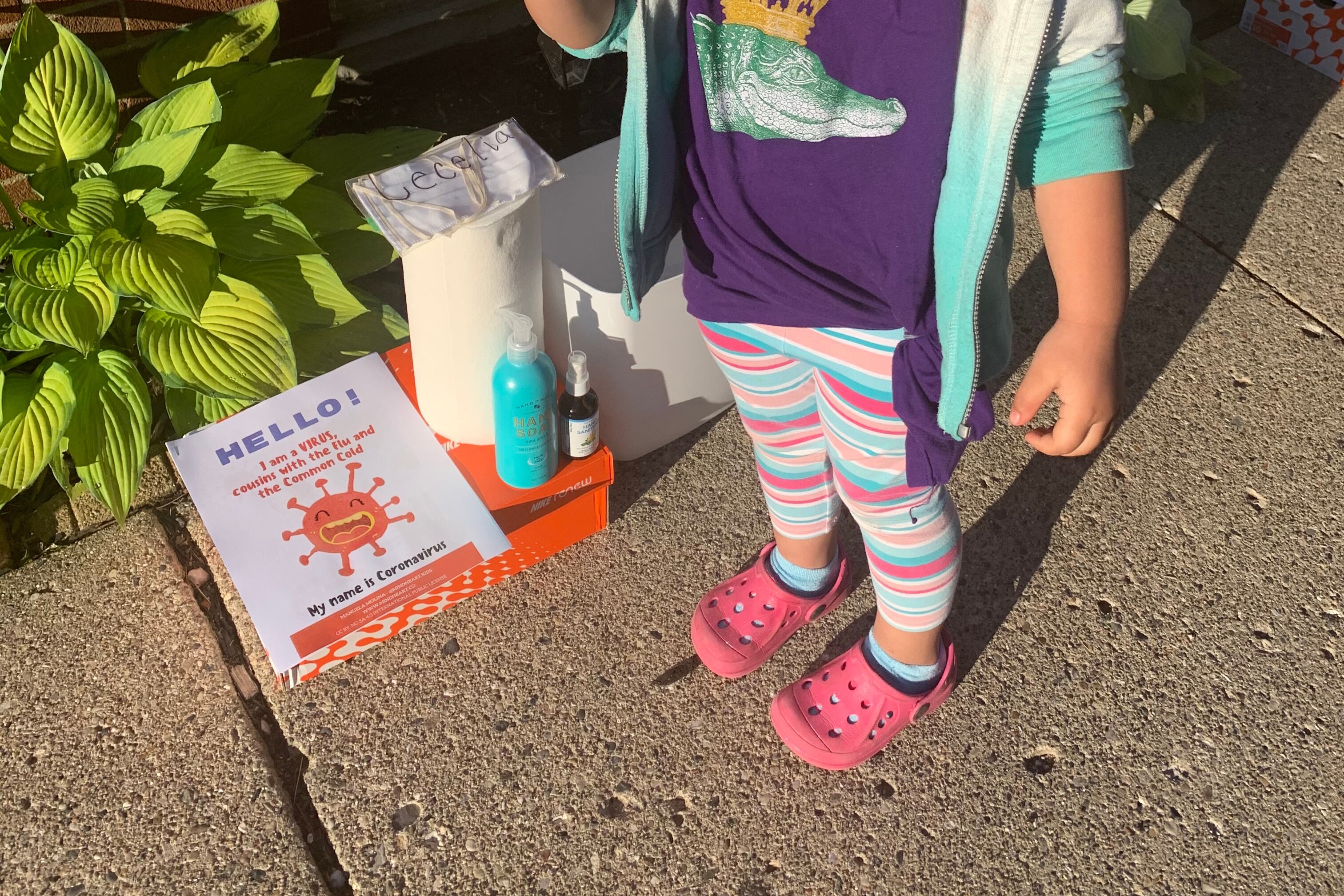

Even if the new funds manage to stabilize or increase the state’s child care supply, the benefits to Michigan children could be muted at first by the pandemic. Some providers say their enrollment is still down as parents continue to shield their children from the risk of COVID. Meanwhile, wages for child care workers remain low, and providers say they are struggling to hire teachers.

Some details about the new funds have yet to be hammered out by state officials.

Nina Hodge, a child care advocate and owner of Above and Beyond Learning Center in Detroit, said it’s not yet clear which areas will be deemed to have child care shortages and be eligible for extra funding.

“Who has access to this? Who’s going to be able to get the money?” she asked.